Toyo Ito: Rethinking Architecture from Modernism

A transcript of Toyo Ito's 2021 Current Work lecture.

Current Work is a lecture series featuring leading figures in the worlds of architecture, urbanism, design, and art.

The following is a transcript of “Rethinking Architecture from Modernism,” a Current Work lecture by Toyo Ito.

The lecture, which took place on June 17, 2021, was introduced by Toshiko Mori, founder of New York-based Toshiko Mori Architect. (Watch a video of the introduction, followed by a post-lecture conversation between Ito and Mori, as well as an audience Q+A.)

*

Good evening, everyone. It’s a great pleasure to give a lecture from Tokyo. I will speak Japanese and Noriko Takiguchi will translate to English.

Thank you, [Toshiko] Mori-san.

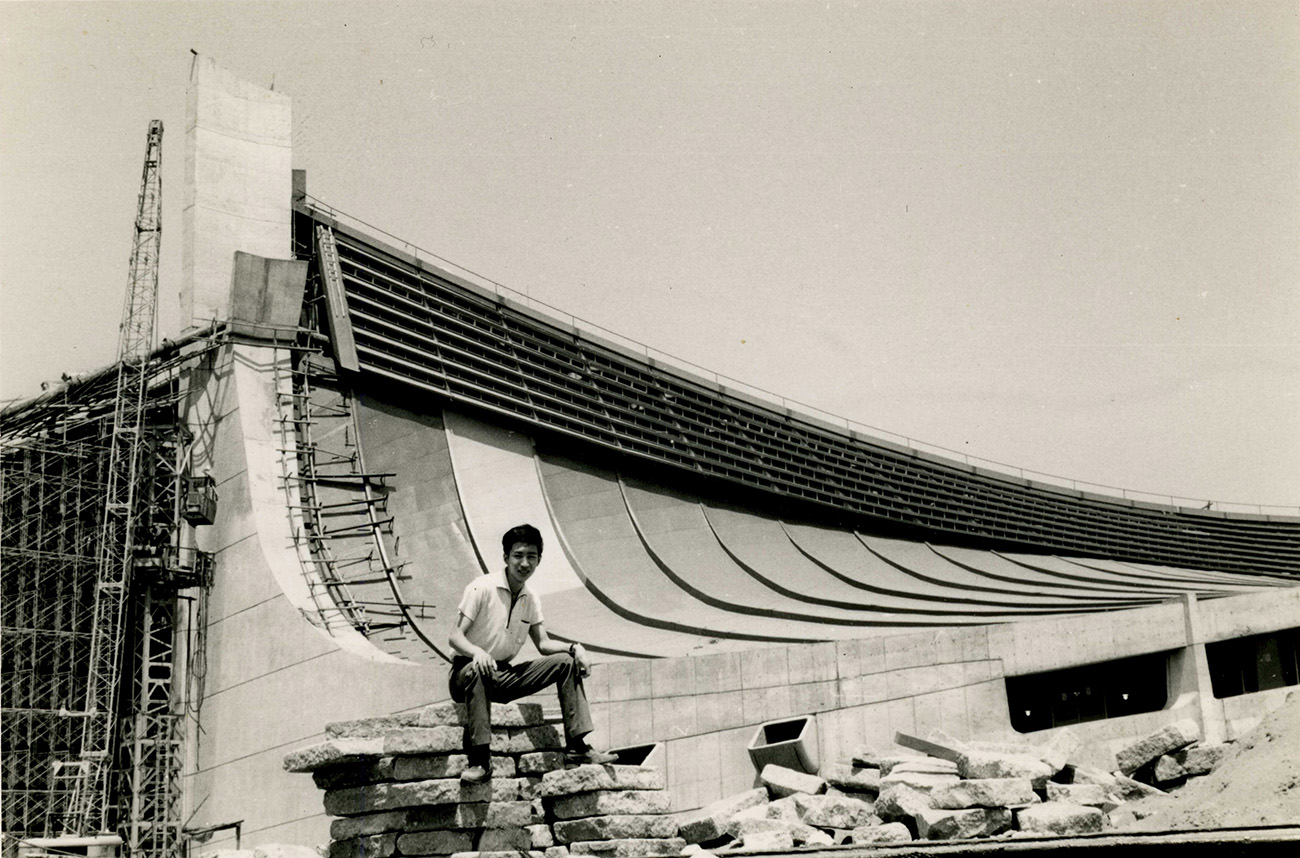

I want to start my lecture with this photograph, which was taken 58 years ago, when I was a fourth-year undergraduate architecture student. This picture was taken right before the last Tokyo Olympics in 1964.

Toyo Ito seated in front of Kenzo Tange's Olympic Stadium. Image courtesy of Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects

This shows the part of the Olympic stadiums designed by Kenzo Tange. The structure in the back is the Olympic pool, and in the foreground is the basketball stadium. These stadiums by Tange are still considered among the best structures in Tokyo. Soon they will be named as one of the National Treasures of Architecture in Japan.

Here you can see the interior of this bigger stadium [image not shown] with a pool and the light coming in from above. Later, after the Olympics, this stadium was converted into volleyball courts as well as an event space.

Last year, another main stadium for the new 2020 Olympics was built by Kengo Kuma and a team of firms including Taisei Corporation.

This is the exterior of this stadium [image not shown], which awaits the opening of the Olympics in a month. I would say in comparison to 1964, Tokyo is awaiting this Olympics in a rather cool, cynical manner—not in a very excited, enthusiastic way.

As you may know, our team was defeated in this competition for the stadium, but I would like to start by explaining our proposal.

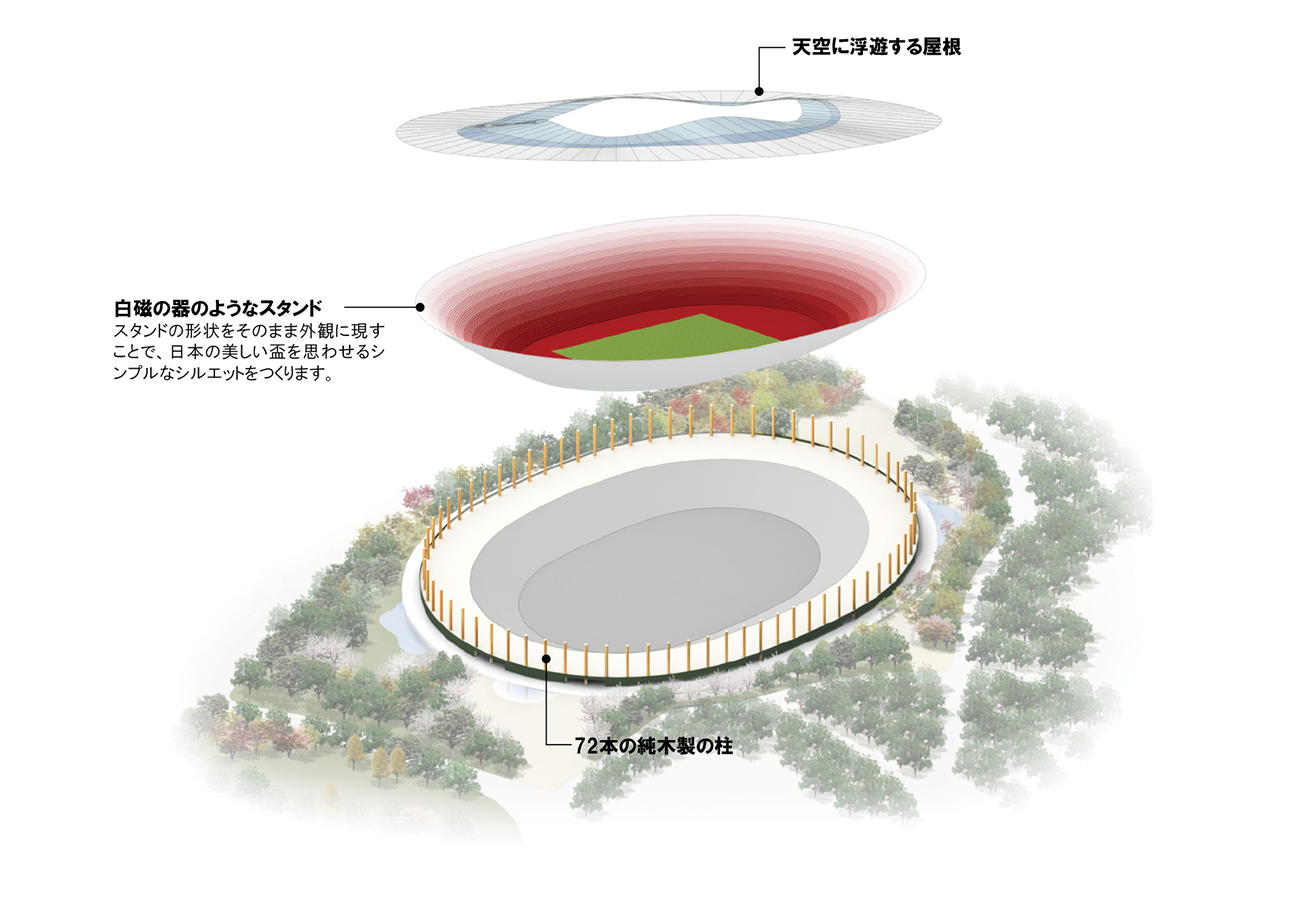

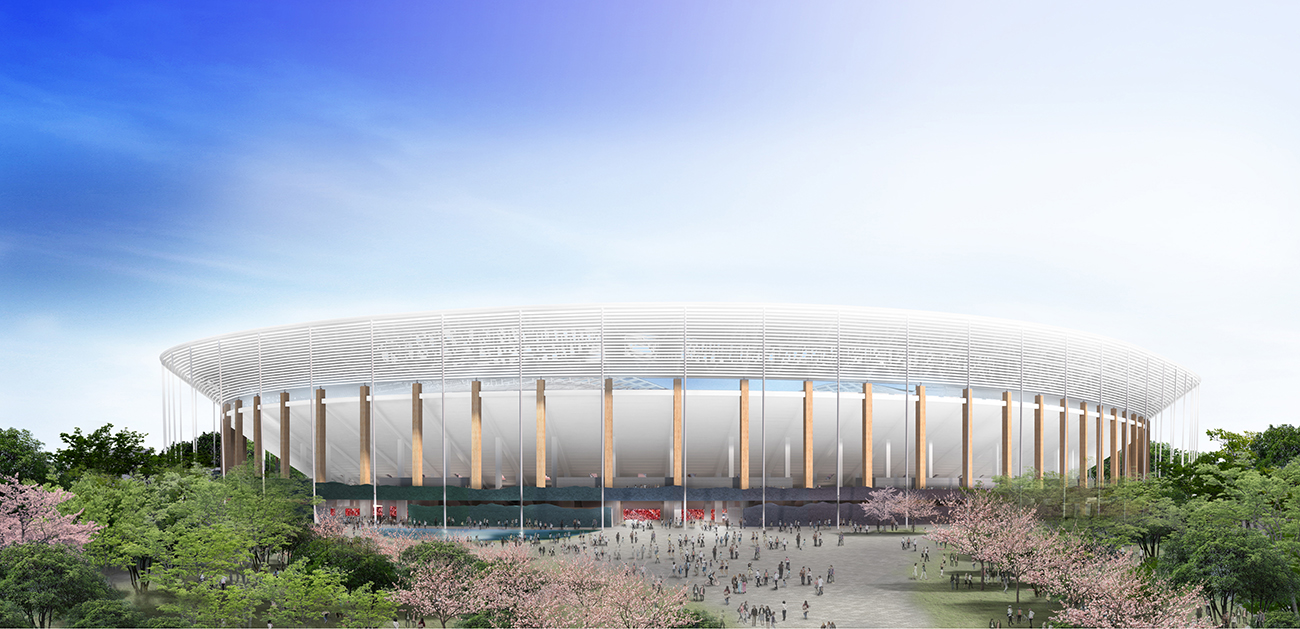

This is the exterior of the stadium that we proposed, which features distinctive wooden pillars supporting the structure.

Exterior view of the Japan National Stadium proposal. Image credit: Joint Venture of Ito, Nihon, Takenaka, Shimizu, and Obayashi

Working within this very limited area was quite challenging, considering that the stadium needed to hold up to 68,000 people. In the 1964 Olympics, there was another smaller stadium on the same site. For this Olympics, we needed to build a stadium that could hold an additional 10,000 attendees. Originally, I had insisted that the old stadium should be just remodeled to fit the new audience capacity. However, it was demolished, thus drawing me to participate in the competition.

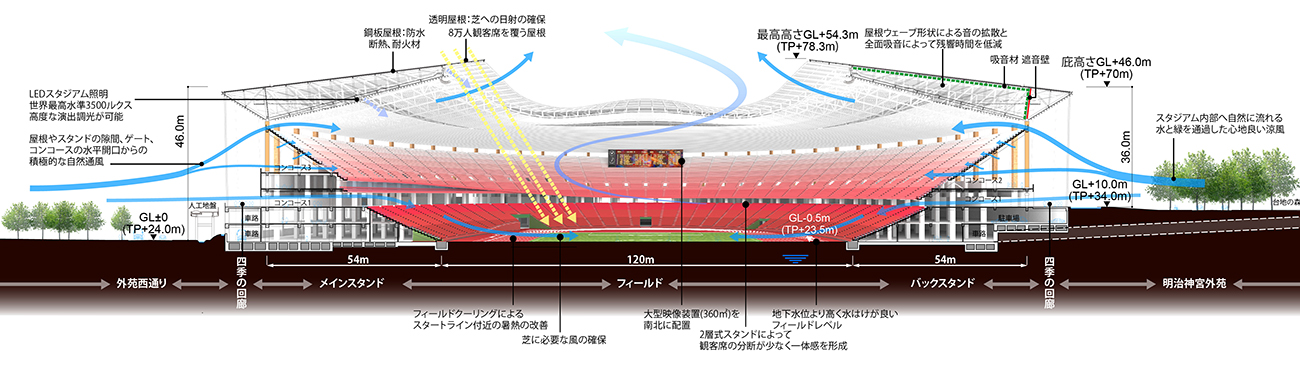

My idea for the stadium was composed of three parts: the 72 wooden pillars, which in part support the main stadium like a tray, and the porcelain tray-like stand, colored in a red-to-white gradation from the base up, with the white connected to the cloud-like ceiling.

The pillars, which are 1.3 to 1.5 meters in diameter and 20 meters in height, are made of laminated wood.

The red color of the main stadium expresses the energy of the earth. The idea around the gradation was to move the heat of the earth upwards through the audience and then penetrate the sky, transitioning to white. We planned to have many trees planted in the surrounding area to bring in as much cool air from outside as possible and support the interior using natural energy.

The Olympics are going to be held from the end of July to August, which is the hottest season in Tokyo. The main events are planned to be held in the evening, so I designed the ceiling to have video and light projections to help create a vibrant and exciting atmosphere.

Interior view of the Japan National Stadium proposal. Image credit: Joint Venture of Ito, Nihon, Takenaka, Shimizu, and Obayashi

It was disappointing that the competition was ultimately judged not based on concept, but rather simply on construction costs and time. I have to say that our construction costs were not very different from those of the winning team, so it was a regretful experience altogether.

After this stadium project, I became very interested in wooden structures. I would like to introduce two wooden buildings that are currently under construction.

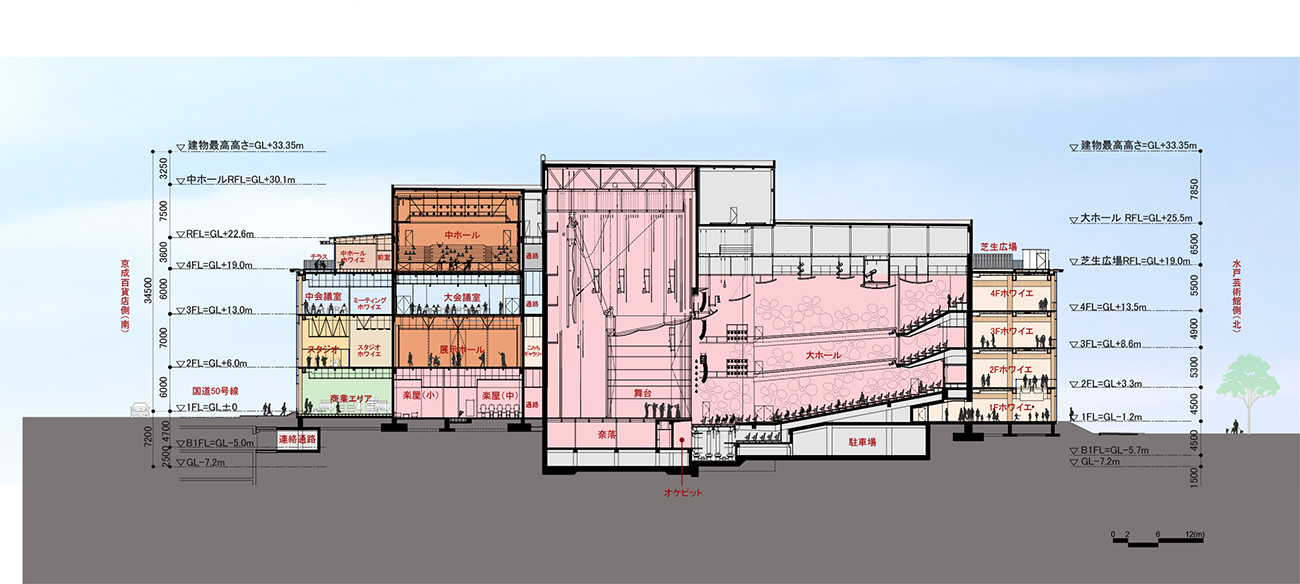

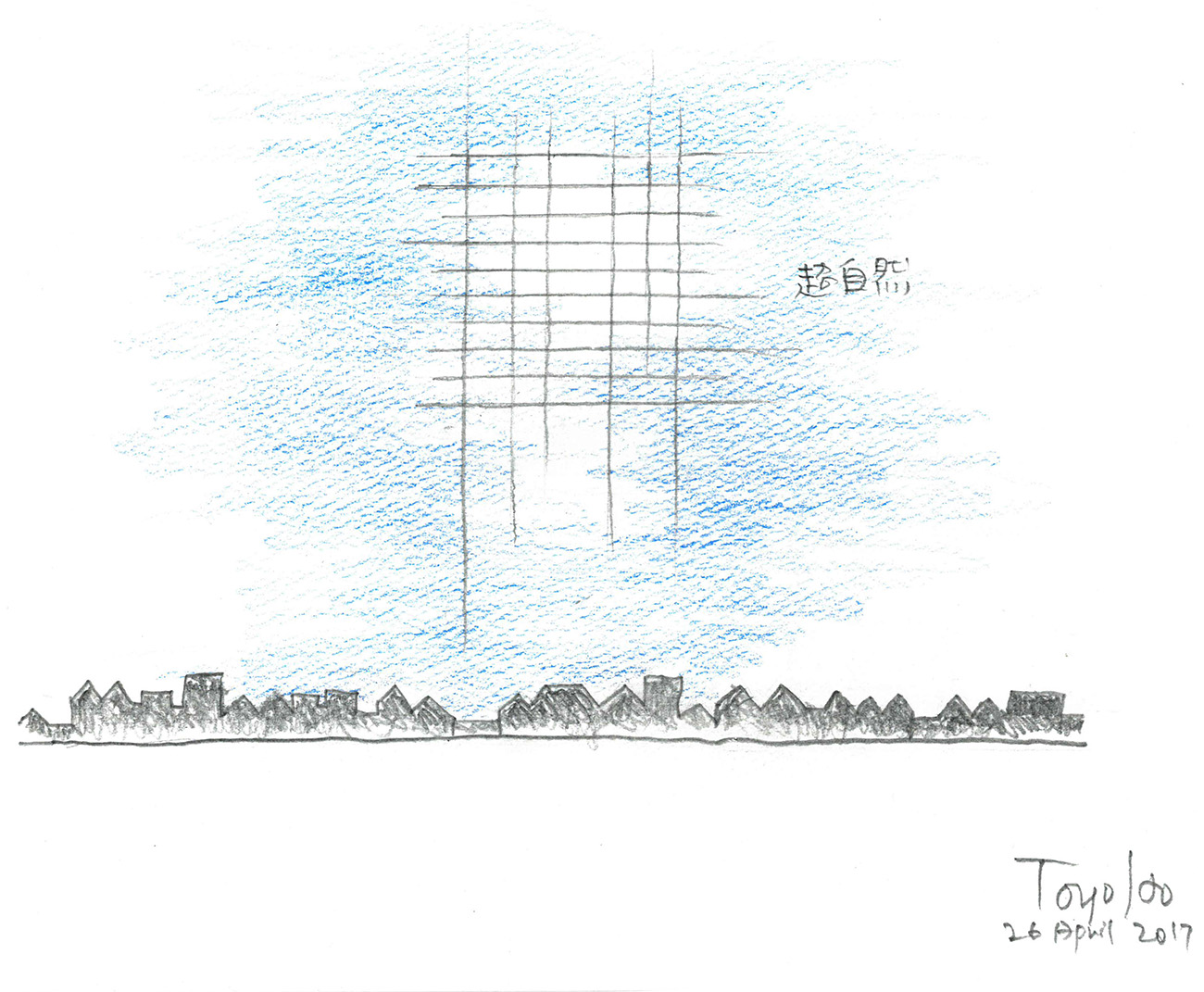

The first is located in the city of Mito in Ibaraki prefecture, just northeast of Tokyo. In the center of Mito, we are building a multipurpose theater and civic center that holds up to 2,000 people. The theater itself is going to be built in reinforced concrete, but it will be surrounded by a cross-hatched wooden structure.

As you can see in this section, there’s the central theater with a capacity of 2,000 people. On the upper left side, there is a smaller hall with a capacity of 500. Surrounding this hall are several studios and conference rooms.

This is the entry area to the 2,000-seat hall, which I expect to be used as a multipurpose space on a day-to-day basis; it will probably be used more frequently than the hall itself. The wooden structure is made of laminated wood pieces 60 to 70 centimeters square. In Mito, there are a number of historic timber buildings that are still in existence, so we wanted to pay homage to this context when creating this space.

Another project that uses wood is an academic building for Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. The structure is over 200 meters long and six stories tall and will be built nearly entirely in wood. The only area that will be in concrete is the elevator, but all other parts will be made of wood. The classrooms will be located on the two sides, and the central area will consist of a continuous atrium with shared spaces such as a resource lounge and an auditorium. The central area will have a span of 11.5 meters, flanked by larger classrooms on the lower floors on both sides. Smaller faculty and research offices are on the upper floors.

The wooden pillars are placed at a 3.3- to 3.5-meter span. You can see that the hallway curves towards the end.

The project is slated to be completed within the year, and the Mito Civic Center project will be completed in 1.5 years and is planned to open in two years.

In the next section of my lecture, I would like to share my thoughts on the redevelopment of the Shibuya area in Tokyo. Shibuya is the area where my office is located, but this sort of redevelopment is not limited to Shibuya; many areas of Tokyo are undergoing similar redevelopments for the Olympics.

This image shows the area around Shibuya station in development. Within the next four to five years, there will be six to seven new high-rise buildings here.

This is one of the buildings which is already completed [the Shibuya STREAM Building, left of center in the photograph]. All floors are occupied by Google.

This is another completed 250+-meter-high building in the area [the Shibuya Scramble Square Building, pictured with the top floors in construction].

These developments are characterized by the “urban cores” that house elevators and escalators and serve as connective channels between the subway, high-rise buildings, and pedestrian decks. My staff members pass through this area every day to get to our office, and not one of them believes that it has made their lives easier; rather, movement has become increasingly convoluted. I feel that these redevelopment plans are not aiming to improve the quality of life for residents or commuters, but rather to further commerce and improve economic efficiency.

In this manner, the more high-rises are built, the further we are driven away from the natural life on the ground level, and the more homogenized our living spaces become.

My concern about this process of homogenization is not just in terms of the built environment, but also that, by extension, the lives of the people who work and live here become homogenized and monotonous as well. I think these days, people in Tokyo appear very unexpressive and emotionless. The verticalization fosters detachment from nature.

Next, I would like to talk about the 3/11 Tohoku earthquake, which Professor Mori mentioned in her introduction as well. There are many villages and cities along the Tohoku coast like those I showed in the video [not shown] that were destroyed by the earthquake. Ten years after the earthquake, we see a lot of these protective walls built along the coastline. The walls create a dividing line between the communities and the ocean, similar to how the urban high-rise buildings are driving a wedge between humans and nature. In this area, the majority of people who were living along the water were in the fishing or farming industry, leading very different lifestyles from the Tokyo residents mentioned earlier.

The people who lost their homes and communities were placed in temporary housing structures provided by the government. Even ten years after the earthquake, there are still many people who live in these facilities.

After seeing this situation, I, together with a group of young architects, proposed and started the Home-for-All projects.

This is one of the wooden project houses, built within one of the temporary housing communities.

The community residents and students worked together to build the structure, and after it was completed, we would gather to eat and drink in the space. The residents in particular enjoyed this atmosphere.

Altogether, the architectural team built 16 of these Homes-for-All in the Sanriku region. This is a Home-for-All built in the city of Rikuzentakata. We used cedar trees that were uprooted by the tsunami to serve as pillars for the structure.

This is the scene of the opening. The bottom third of the building was later infilled with earth from a nearby mountain to elevate the area, so the house was once torn down but has since been rebuilt at a higher elevation.

Next, I would like to present another project completed after the earthquake. Minna-no-Mori (A forest for all) Media Cosmos, a multipurpose civic center with a library at its core, is located in Gifu, a city with a population of around 400,000.

The building consists of two floors, and this image shows the plan of the ground floor.

In the center, there is a closed shelf library enclosed with glass. This building is rather large: 90 meters wide and 80 meters long. There is a gallery and auditorium located on the right-hand side, and on the left are gathering spaces for community members, along with a small restaurant and a convenience store.

Here is the first-floor workshop area, where a children’s activity is taking place in the photo. The space is popular among the community and is used by a range of people; though the population of the city is 400,000, an estimated 1.2 million people visit the space every year.

This is the open gallery space on the first floor. We’ve designed a space where people don’t only come here to read and borrow books, but also to have encounters with friends and fellow community members, making it a genuine community space.

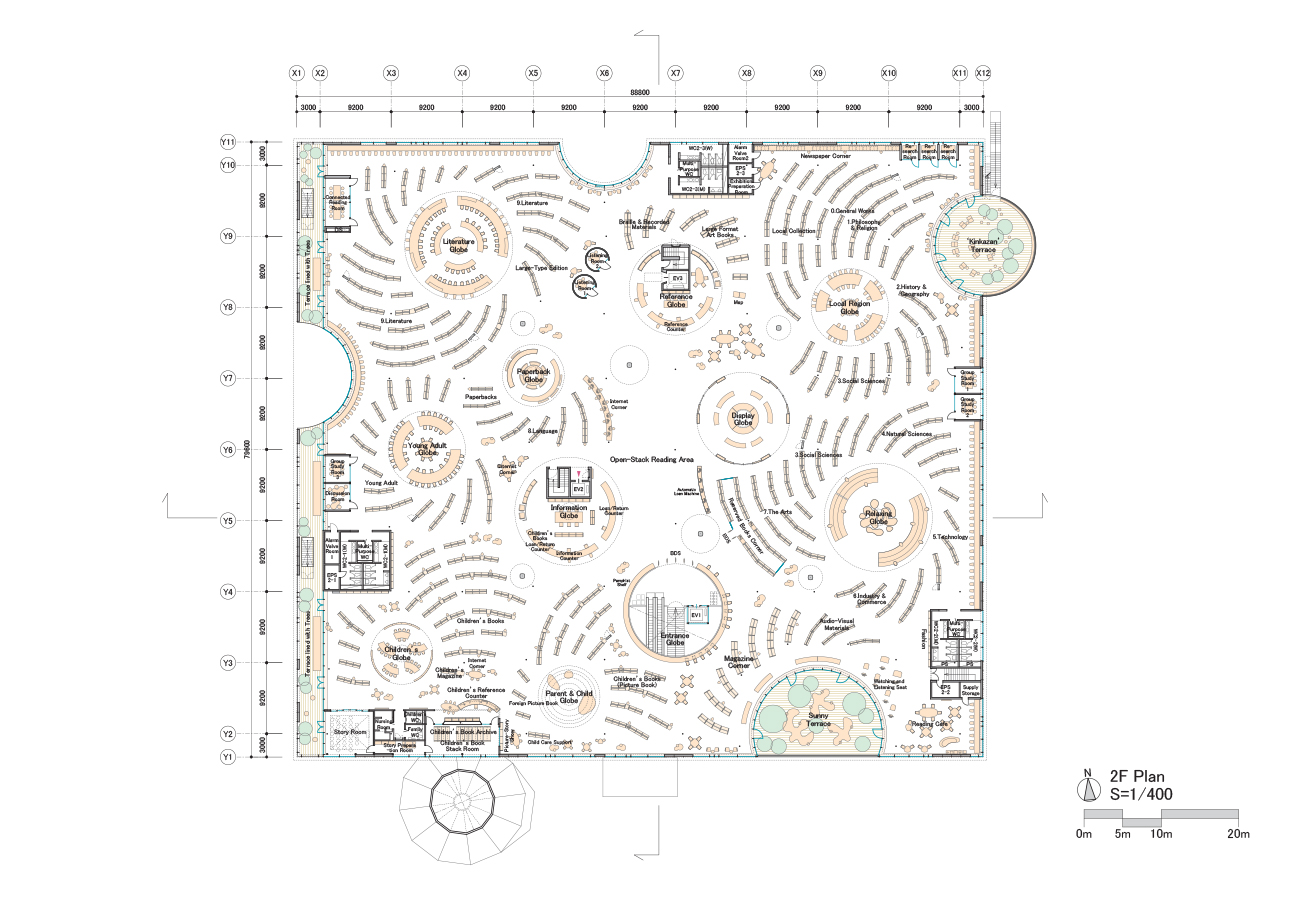

This is the plan of the second floor. The circular forms are reading areas, and the bookshelves spiral out of these nodes.

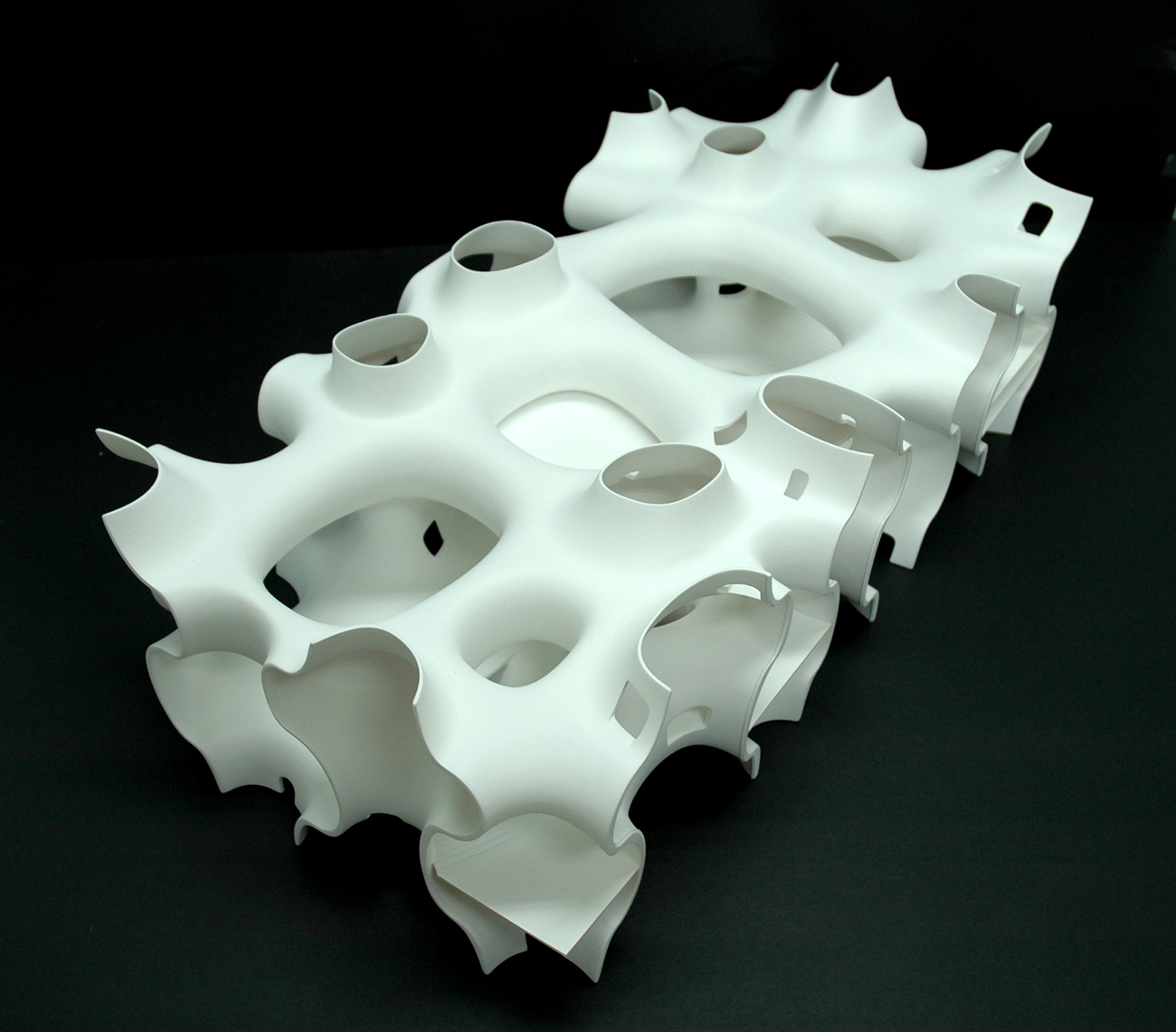

This section is rather an important one, as it illustrates the concept of the building. This site is very close to a big river in Gifu, and the area is rich in groundwater, which is utilized in a climate-controlling system, heating and cooling the space from the floor up. As the hot or cool air moves upwards from the floor, it is circulated slowly through the whole building. In the summer, it will be drawn out from an aperture at the highest point of the building, which is closed during the winter to allow the hot air to be stored in these umbrella-shaped “globe” areas. There are 11 globes of different sizes hanging from the ceiling. Natural light flows in from above, enveloping each globe.

The undulating, wave-like roof is built with wood. In order to create the smooth curves, we used locally sourced wood cut into 2-centimeter-thick slats, which we stacked on top of each other in 21 layers, set at a 60-degree angle.

We came to this form based on structural, engineering, and environmental factors. The curvatures of the roof echo the forms of the surrounding mountains, and also serve to regulate air by discharging hot air from above. Structurally, it’s also stronger than a flat roof.

The last project that I would like to show you today is the National Taichung Theater in Taiwan, an opera house which opened in 2016. As you can see, the site is located in a park within a residential area, surrounded by new apartment buildings.

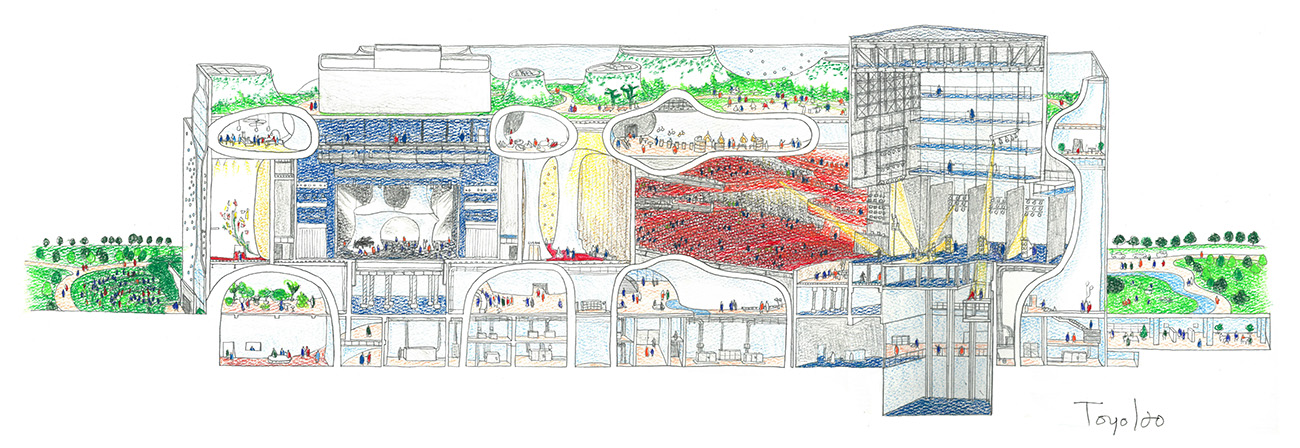

This building holds three theaters. The Grand Theater, shown in red, has 2,000 seats, while the blue Playhouse holds 800. There is a smaller theater underground with 200 seats.

The structure is very complex and was built entirely onsite using concrete.

This video [not shown] shows the process of building the structure. First, we built a truss wall at a factory onsite. We attached mesh to both sides of the truss wall before pouring in the concrete between the mesh. This was a rather primitive way of construction, and it took around 2.5 years to build this structure.

This next film [not shown] shows the scene at the pre-opening of the building in 2016. Despite the title of the “opera house,” the environment itself is quite casual, and people wander through the space as they would a city street or park. Apart from the three theaters, there are a number of pockets of space across the building that are used for smaller acts, creating an environment akin to that of a street performance.

The whole process, from the competition submission to the construction, took 11 years.

In the last few slides, I would like to share my thoughts on this idea of two kinds of water. I think there are two kinds of water that connect people with the world. The first water is the physical one, which comprises our bodies and has existed unchanged from ancient times. In this modern era, humans are also connected with another type of water: information. The modern person lives with a bottle of water in one hand and a smartphone in the other, so to speak.

I believe that architecture has an unchanged purpose of connecting the physical water of human beings to their surroundings, to think critically about how the human body is intertwined with and embedded into the built environment.

Modern peoples are increasingly prioritizing the information water, which is beginning to overwhelm the first form of water.

This is another scene from the Shibuya area [not shown], where people are wandering the streets in pursuit of the information water in an increasingly homogenous environment.

This is my final message. In this regard, it may seem that architecture is trying to realize an outdated purpose, but my practice continues to center the first, physical water—creating architecture in order to reinforce and harmonize the relationships between the physical water in humans and the built environment.

Transcript lightly edited for clarity.

Explore

Hiroshi Sugimoto lecture

Sugimoto, a renowned photographer, explains his turn toward architecture.

In conversation: Wang Shu, Lu Wenyu, and Toshiko Mori

The Amateur Architecture Studio founders speak with Toshiko Mori.

Marina Tabassum: Dwelling in the Ganges Delta

The Aga Kahn Award-winning architect speaks about architecture as a means for community connection.