The Menu of the Day

For APRDELESP, running a network of commercial and cultural spaces in Mexico City offers the chance to rethink design practice.

September 28, 2021

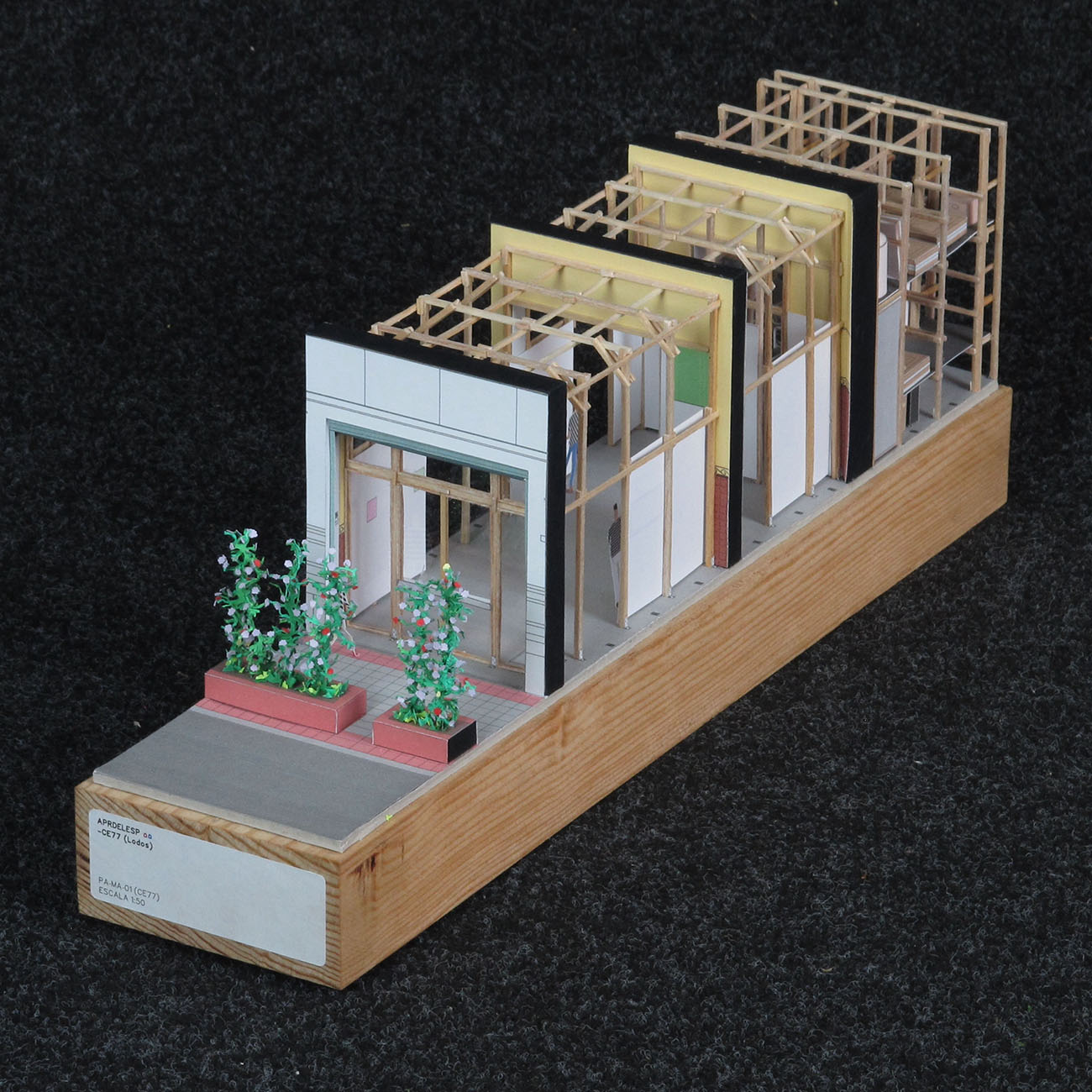

Parque Experimental El Eco, a temporary installation in Mexico City's Museo Experimental El Eco. Credit: APRDELESP

The designers behind Mexico City’s APRDELESP view dominant models of art and architecture practice as precarious and elitist, with little to offer most artists, let alone society at large. To counter a system they see as fundamentally broken, partners Guillermo González Ceballos, Rodrigo Escandón Cesarman, and Ricardo Roxo Matias have spent almost a decade trying to construct their own. Through the creation of a network of “subspaces”—physical and digital spaces spread throughout the Mexican capital—APRDELESP seeks to create opportunities to design, experiment, and engage with the public in different ways, eschewing traditional hierarchies.

The process of envisioning and running these spaces, which has encompassed everything from selling furniture to bussing tables and planning events, has deeply influenced APRDELESP’s approach to more typical architectural commissions. The League’s Alicia Botero and Sarah Wesseler spoke with Escandón Cesarman and Roxo Matias about their work.

*

Sarah Wesseler: You’ve been running subspaces in Mexico City for a decade. Are there lessons from this project that you’ve applied in your practice more generally?

Rodrigo Escandón Cesarman: I think the most important lesson has been that the physical elements of architecture—the walls, the roof, but also the projector, the plants, the electric outlets—all this is only part of the operation of a space, in the end. In this sense, being waiters and cooks in our own cafés has been as important as being architects. We take the whole operation seriously.

Scenes from APRDELESP subspaces Muebles Sullivan (a furniture store) and Café Zena. In keeping with the partners' commitment to transparency and experimentation, APRDELESP refers to its projects as case studies and maintains extensive documentation of every phase on its website; Muebles Sullivan and Café Zena are Case Studies 19 and 0.1, respectively. Credit: APRDELESP

We think about architectural drawings like a café checklist, or as the menu of the day: something that has to be updated quickly, and that the client has to be able to see and understand quickly. It’s about understanding that serving a coffee is just as important, and has to be just as fast and easy, as making a plan or an axonometric. This way of approaching architecture, where everything is about operations, is something that helps explain the design process for the subspaces and our other projects.

Wesseler: With this project, how important is the urban scale to what you’re trying to achieve? Is creating a network of spaces in different neighborhoods and offering different ways for people to engage with the city a priority? Or do your decisions end up being more about, “Here’s a space, here’s an opportunity, this could be fun, let’s do it?”

Escandón Cesarman: Well, because we haven’t had the opportunity to do a public project, we’ve thought a lot about how these spaces—which, in the end, are private—could be more open to the public. And to this end, we think about what a park would be if it were loaded with infrastructure. In particular, one of the subspaces—Parque Experimental El Eco, it was called—explored this idea: What would it mean to create a public space that’s full of infrastructure: speakers, projectors, screens, plugs, Wi-Fi, free water and coffee, lighting around the clock, and tables and chairs?

Parque Experimental El Eco (Case Study 44). Video courtesy APRDELESP

Thinking on an urban scale, we’re very interested in how public space could have what we call “the luxury of infrastructure”—these things that are sometimes more common in houses and other private spaces. How can you create a park with exuberant infrastructure?

For example, in Café Zena, which is a restaurant that was open from 2012 until the start of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, there was a very long table that was divided in two, but there was also a projector, speakers, and electric outlets for every visitor. Everyone could connect their computer at the table and play audio and video. And sure, we were under no illusions that it was a public space, but we tried to think of it as a kind of park filled with infrastructure.

Café Zena. Video courtesy APRDELESP

Wesseler: Hearing you talk about the project makes me think that in New York, it would be difficult for artists to rent a storefront with the goal of having it be a hybrid cultural space; it’s too expensive. This kind of thing has obviously happened here at various points—in the ‘60s or ‘70s, artists opened different kinds of spaces in Soho, etc.—but the rents are just too high for that now in most of the city. But it is useful for cities to have spaces that approach the idea of culture in different ways.

Escandón Cesarman: I think one problem with art spaces, including those that were founded in New York in that period, like The Kitchen or Storefront, is that it’s very difficult to attract people who aren’t already part of the art or architecture worlds. In Mexico City there are a lot of independent art spaces: project spaces, small galleries, etc. But we think it’s very valuable that our spaces with a cultural program have also been a café or a furniture store. In Muebles Sullivan, for example, we also sold paletas heladas (popsicles)—we’re interested in really making the spaces open to unexpected encounters.

For us it’s important that, for example, anyone can enter and drink a coffee and feel comfortable and not feel like they’re inserting themselves into an art space that they don’t understand.

Wesseler: Your work on another art-related project, the Material Art Fair, came about through the subspaces. Can you explain how this project got started and how it’s evolved over time?

Escandón Cesarman: Yeah, we started working on the project because we met the organizers in the subspaces. Suddenly we were spending time with them, especially at Café Zena and Muebles Sullivan. And then while we were hanging out one day, our partner Guillermo criticized the first two editions of the fair.

The organizers knew our work from the subspaces; they were familiar with them not just as architecture, but also for everything that happened there. So we started creating a subspace with them too. During the early days of the fair, for the third edition in 2016, they wanted to have a coffee bar there, but they didn’t have anyone to run it. So we created a coffee shop that lasted only while this edition of the fair was open. We called it Café des Artistes as a silly joke; we wanted it to sound like the name of a fake Parisian café at Disneyland or something. When the fair opened to the public, we were finishing the space and making sure that everything was going well, but we were also making coffee.

The first time we designed the fair was that edition, in 2016; we’ve done five in total. The last three have taken place in the same building, which has allowed us to approach it as if we’re redesigning the same building every year. It’s been very interesting for us—an iterative process that has different outputs every time.

Material Art Fair schematic design development. Video courtesy APRDELESP

Wesseler: So this relationship started with you critiquing what the organizers had done in the past. How did that critique inform how you then approached the project?

Escandón Cesarman: The main criticism was that they didn’t give enough importance to the space, which seemed strange to us, because in the end, art fairs are social events where space is very important.

They didn’t think beyond the traditional art fair setup: a conventional trade show that has booths lined up and a series of aisles. It seemed like a missed opportunity not to think beyond this, or about what other kinds of spaces there might be, or what other characteristics they could have.

Alicia Botero: Could you talk about what kinds of spaces you thought could be part of the fair?

Ricardo Roxo Matias: There’s a tendency at art fairs for spaces that aren’t dedicated to exhibition—that aren’t booths or galleries—to be a bit like annexes. They’re given less importance, because obviously nothing can be sold there. But we tried, working with the fair’s organizers, to make these common spaces feel as important as the exhibition spaces, or at least design them with the same level of care.

Wesseler: When you were running the coffee bar at the fair, did the visitors or exhibitors know you were also the architects? I imagine you had some interesting conversations.

Roxo Matias: People working at the fair realized that they had seen us at some point during the construction and in all the chaos that was going on during that period. The construction workers and the people who were setting up the booths would see us in the café and ask us what we were doing there.

Escandón Cesarman: Yeah, and one thing that’s changed over the years is that, although we’re not running the coffee bar anymore, we’re doing the construction ourselves. The fair has this intermediate quality: It’s an event, but also a building. For the last three editions, we’ve designed a three-story building: It has finishes, paint, and utilities. Truly, it’s like building a building in a week.

But what we found is that building contractors don’t have the capacity or infrastructure to build a building in ten days, and event producers don’t have the ability to do construction to very precise specifications. So starting with the last edition of the fair, the 2020 edition, we started to build all of our own projects. Now we have the capacity to do every stage of the design process in the office.

So the lessons we’ve learned from the subspaces have become more important with the fair, and now that we’ve also started to dedicate ourselves to construction, we’re going back to this logic of seeing of architecture as operations, thinking that making a drawing, creating a plan or an axonometric, and even building the fair is like serving a coffee: It’s equally important, and it has to be equally easy and frictionless. In the end, just like waiting on a table in a café, building a building means being there resolving problems, and the drawings—just like a menu or a list of goods in a café—are just the tools to do it.

Wesseler: Some of your subspaces have closed due to COVID. How do you see that project developing in the future?

Escandón Cesarman: The subspaces have been opening and closing, including before the pandemic. Some have had a start and finish date from the beginning, and we haven’t been fixated on the idea that any of them will last forever. After COVID hit, we shut down the ones that involved paying rent and dealing with all the trouble associated with keeping them alive during the pandemic, since no one knew how long it would last. One survived: MACOLEN, a risograph printing press that’s still open.

MACOLEN (Case Study 49). Video courtesy APRDELESP

I can talk a bit about the building we’re in as we speak—the printing press is in this building, and we also had a bar called La Pipí here that closed due to COVID. The press has continued to operate, although it’s not open to the public; I think La Pipí should be very easy to reopen when it’s safe to do so. And for now, the building where our offices are is also where we live, the three principal partners.

La Pipí (Case Study 66) Video courtesy APRDELESP

We think about this building a bit differently than the subspaces, but we have been here for six or seven years, remodeling it and thinking about what we want it to be over time. We want it to function as a kind of institution open to the public where anyone can consult our archive and that of a community of artists close to us: artists, writers, designers. So we think of it as a kind of infrastructure enabling us to work and share our work.

Interview translated from Spanish, condensed, and edited.

Explore

Designing Through the Lens of Culture

For Studio Zewde, the process of learning about the communities it serves is a creative act in its own right.

Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.

Flash and spectacle in the face of austerity

Debroit-based Anya Sirota discusses the relationship between architecture, culture, and urban vitality.