Interview: The Living

David Benjamin founded The Living in 2006 with the mission of “creating the architecture of the future” through the exploration of “how new technologies come to life in the built environment.”

In March 2014, on the occasion of his Emerging Voices lecture (video embedded below, also available here), Benjamin sat down with League Program Director Anne Rieselbach and Program Associate Jessica Liss to discuss his practice.

Jessica Liss: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

David Benjamin: We’re interested in exploring new ideas for the future of architecture, and we aim to make and test them in a way that challenges and exposes these ideas to cultural, social, and technical conditions with a lot of the functional requirements of typical architecture.

The Gray Rush, commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art, is an exploration of a future when lithium—or “gray gold”—is one of the world’s most valuable resources due to its use in lightweight batteries for cell phones, laptops, and electric cars. The project explores both global flows of resources and personal human experience in relation to technology, society, and the built environment. | Photo courtesy of The Living

Liss: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practicing in today’s economic, professional, and intellectual economy?

Benjamin: There’s never a better or worse time for far-out ideas, but I think this is a really interesting moment for interdisciplinary collaboration. Now more than ever there’s recognition in practice and research that the tough problems of our times, including architectural and urban problems and, most poignantly, issues of climate change and the environment, require this approach.

We definitely have a bit of a DIY attitude, in that we can quickly learn enough about almost anything to do an experiment with it and have a fresh approach, but unlike some types of practices, we don’t feel that we have to do that all ourselves. We always learn just enough about something to have an intelligent conversation with the expert, and then we immediately seek out the expert as a collaborator or partner. The great thing about the field of architecture is that we can reach out to those people who can help solve problems that we recognize in our work.

Liss: You founded The Living in 2006 with the mission of “creating the architecture of the future.” So what is the future and how has your conception of what it holds evolved over the past eight years?

Benjamin: While a lot of our projects and research are about the future, and we allow ourselves to be utopian and forward looking, we also want to experiment with the here and now. We like to address today’s urgent problems with today’s available technologies, so we’re not just sketching out some vision of a future city and future technologies that are so far away that we can only draw them. We actually want to prototype them. With that in mind, it’s easy to shift between our “current” and our “future.”

In Street Life, commissioned by the Shenzen and Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture, LCD screens displaying messages are embedded in street food soup bowls. | Photo courtesy of The Living

When we first started doing projects in 2006 with new technologies, a lot of our work was with digital sensors and micro-controllers. It’s hard to believe, but iPhones and Arduinos didn’t exist yet. I used to be very confident that I knew about every project that applied those technologies to buildings or cities, because there were so few. But now, or even three years ago, there’s no way I could possibly know everything going on with explorations using sensors, Arduinos, and dynamic LED lighting. It’s much easier to use those tools and the equipment is cheaper, so the projects are getting more interesting. But most importantly, the community around these projects has grown: people do a project, publish their process and results, and then other people ask questions about how it was done and discuss the project. Once there’s that community of people sharing projects with an open source ethos, that’s kind of unstoppable. It’s not really the technical stuff; it’s the social stuff.

Liss: How and when did you become interested in this work that combines architecture and information technologies?

Benjamin: Some of that comes from just thinking about what’s next, so it’s natural to think about technologies. But we also believe that no idea should be fetishized without being questioned. We aim to be both obsessed with the idea and then also stop and think about what it really means. We want to apply technologies for a purpose; for explorations of public space, public awareness, and urgent issues like the state of the environment, not just for their own sake.

Mussel Choir, commissioned by the U.S. Pavilion for the Venice Biennale 2012 and developed in collaboration with Natalie Jeremijenko and Mark Shepard, is a monitoring system using live mussels as bio-sensors and vocalizing changes in water quality through artificial intelligence and natural intelligence. | Photo courtesy of The Living

A few of our projects use technology to collect information about the environment, and then make that information visible or digestible. In River Glow, for example, we were interested in not only measuring water quality, but also making it legible in public space by having lights that change color based on the how clean the water is—translating the world of data to the world of experience by creating an atmosphere. Lately, we’ve been experimenting with how we can add to this by letting people know that there’s something they can do and encouraging that. That’s a really difficult step. With the water quality project, we’re trying to integrate an opportunity for people to feed fish with food that helps take heavy metals out of the fish. So we’re combining an awareness of water quality and marine life with the invitation to participate in an action to help the environment.

The Living Light Pavilion is another example of this kind of project. It was commissioned by the City of Seoul, South Korea, through a public art competition. Our proposal shows that public art doesn’t just have to be an inert sculpture; it can be a piece of architecture that’s dynamic and alive. At the time, a lot of new buildings in Seoul were being built with dynamic LED lights, but for the most part they were just displaying a rainbow of colors that had no real meaning. Meanwhile, Seoul was also very interested in the issue of air quality and had installed air quality sensors all over the city. For the most part, air quality is shown as a number, like 200 parts per million. We thought we could merge these two trends together to suggest what could be possible for the city’s approach to air quality and for building facades of the future. In other words, put the air quality data on the building facade so that instead of having buildings display only entertainment lighting, they can display environmental information.

Living Light, commissioned by the City of Seoul, is a permanent pavilion as a map that glows and blinks according to air quality data and public interest in the environment. | Photo courtesy of The Living

Liss: Tell us about the Living Architecture Lab that you direct at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP).

Benjamin: Our lab, which is one of several research labs at GSAPP, is concerned with many of the ideas that we’ve already been talking about: bringing architecture to life and, more and more, using living organisms to do so. There’s a bridge in our vision between responsive architecture that’s using sensors and displaying information and architecture that’s using responsive living organisms to make, for example, the new type of brick that we’re exploring in Hy-Fi at MoMA PS1. These are in some ways very different technologies, but we think that the idea of living architecture encompasses both of those worlds.

We also emphasize open source research and design. Our version, which is not really a strict technical definition of open source, is creating some type of design intelligence that can be reused in the future as opposed to starting every single project with a blank slate and willfully pretending that there are no precedents. It’s a fairly straightforward concept, but it can be difficult to pull off, whether in an academic context where students are continually coming and going, or in a professional context where a client hires a designer and they want that design to be theirs. There’s something to be said for each student having to reinvent the wheel, because you learn something by reinventing the wheel, right? At the same time, it seems like a waste if we don’t immediately understand what’s been done before and build off of it. There’s no shortage of things to be creative about or problems to solve. So in our practice and at the Lab, we document what we do in a way that’s easy for others to understand and build on.

Anne Rieselbach: Have you seen people doing this with your projects?

Benjamin: Yes, particularly in a research project called the Columbia Building Intelligence Project (CBIP), which I run with Scott Marble and Laura Kurgan, where we’ve very deliberately had students leave behind work that others can work off. Students get that idea immediately and there’s really no issue over creative ownership. It might seem that using someone else’s design to get started would limit students’ creativity or make them feel that they don’t fully own the design, but the great thing about creative and motivated students is that there’s always some twist that they can apply to it to make it their own. The projects just get better because of that.

Hy-Fi | Copyright Amy Barkow, Barkow Photo

Liss: You mentioned the Hy-Fi installation at MoMA PS1—what was the impetus for the project?

Benjamin: Hy-Fi puts into action the process I was mentioning earlier of having an idea then pushing it to the limits. The project started with our interest in using natural living organisms to contribute to a new kind of building. And we wanted the design of a building to be an ecosystem that touches on the source of raw materials, the ultimate fate of the materials when the building is gone, labor and jobs, and the culture of the surrounding environment. As our ideas crystallized, we started to see the project as an opportunity to make a structure that temporarily diverts some resources from the earth’s natural carbon cycle and then puts them back in a way that not even salvaged building materials can. Although a lot of the ingredients were there, no one had ever done this kind of thing before at this scale, outdoors, with structural load bearing, so it became a perfect way for us to test the idea.

Because Hy-Fi really is something new, we have a long list of collaborators. First and foremost, Ecovative, which has a lot of experience in growing solid objects out of a living organism and agricultural waste. It’s a good partnership because they have mastered the industrial process and have machinery that can do this at scale, but they have never made parts for an outdoor load-bearing structure. So we can push them to do something new, but they can assure us of what’s possible and then produce 10,000 bricks once we get the exact right formulation. We worked with Arup on structural engineering because they are experts at doing analysis on new materials and forms. Atelier 10 helped on environmental engineering, 3M pitched in with a high-tech reflective material, and another collaborator did accelerated aging to test the durability of a material.

Hy-Fi is another example of a project with totally different materials and technologies that requires the right amount of knowing that it’s possible, but also knowing that it’s never been done before and then executing it.

Salvage City, commissioned by Build It Green!, a material salvage non-profit organization in Gowanus, is a new storefront replacing a brick wall with community space—made out of 99% salvaged materials and offering a new definition of green architecture. | Photo courtesy of The Living

Liss: Switching gears, could you talk about the intention behind the instruction manuals that you’re designing with Build it Green?

Benjamin: Build It Green! is this incredible nonprofit in New York City that salvages building materials, and I’ve been friends with Justin Green, the founder, for many years. They have a new branch in Gowanus, and we’re helping design a new storefront for the store. But I’ve been talking with Justin about salvaged materials for years. 40% of the landfill space in the United States is construction waste. The construction of a typical 2,000-square-foot house in the U.S. generates 8,000 pounds of construction waste. Construction is a very inefficient and wasteful process.

There’s one challenge when you go into a store like Build It Green! looking to construct with salvaged materials: there are many different objects, and usually only one or two of each, so sometimes it’s hard to know how you can make a new project out of this patchwork of solitary objects. So in addition to designing a storefront, we also thought to design instruction manuals for taking some of the salvaged materials and giving them a bigger impact.

Liss: With this perspective on building in mind, tell us about your first large-scale traditional architecture project designing the Princeton Laboratory of Embodied Computation.

Benjamin: That’s a really exciting project for us, in part because it’s a fairly standard architectural commission to design a new building, but also because it’s a building meant to house research about the future of architecture. It’s totally circular in the best possible way and it seems like a natural next step for us. To design the best building, we not only get to consider the standard questions about circulation, cost, HVAC systems, et cetera, but we also get to continue asking the questions we’ve always been asking about technologies and the future. How are we going to be teaching architecture in the future? The main client is the Princeton School of Architecture, but the civil engineering, computer science, environmental studies, and even fine arts departments are interested in using it as well. So what is the future of interdisciplinary collaboration?

We’re also aiming to make this a landmark building for sustainability and to align it with Princeton’s very ambitious sustainability goals. This building brings a discussion about embodied energy to the Princeton initiatives, so not only how much carbon does the building emit once it’s built but how much carbon and how much energy was involved in creating the materials to make the building.

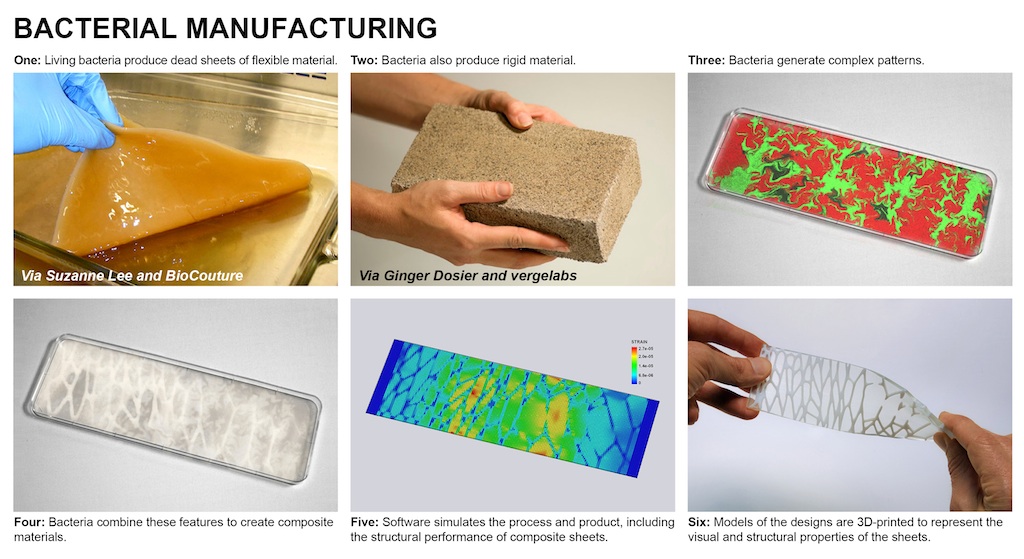

Bio Computation, developed for Autodesk Research and TED Global 2012, is a new design platform that uses synthetic biology to manufacture novel building envelopes with higher performance and greater sustainability than traditional methods. | Photo courtesy of The Living

Liss: What else is on the horizon?

Benjamin: We’re on schedule to complete an Economic Development Corporation-funded installation right beside Pier 35 in the East River by the end of the year. It’s a continuation of the Amphibious Architecture installation we did as part of the League’s Toward the Sentient City exhibit in 2009, but now it will be much bigger, more permanent, and has several other smaller installations as part of it.

We’ve also been doing exciting applied research with three different large corporate clients. I can’t describe this in detail now, but one is a new materials company, another is a software company, and the third is in the aerospace industry. Although these seem disparate, they make complete sense alongside all of our research projects and within our ideas of the environment and public interface. These developments within the practice are in line with what I’ve experienced at Columbia with advanced experimental research and significant ties to the corporate world, with partnerships with Oldcastle Building Envelope, Audi, and Thompson Reuters. I think there’s something in the air about alignments between academic or theoretical research and corporate research and development.

[Since this interview was conducted, The Living announced that it will partner with software company Autodesk to launch Autodesk Studio. –Ed.]

•••

David Benjamin, The Living, Emerging Voices 2014, complete lecture video | Recorded March 6, 2014 | Running time: 44:16

•••

David Benjamin received his M.Arch. degree from Columbia University, where he has been the Director of the Living Architecture Lab and Assistant Professor since 2005. A former winner of The Architectural League Prize for Young Architects + Designers (with Soo-in Yang), Benjamin has subsequently received numerous awards including the New York Prize Fellowship, the Van Alen Institute; a R + D Award, Architect Magazine; the American Institute of Architects New Practices New York Award; and a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship.