The Image of Water

Communities throughout Mexico face severe challenges with water. Addressing them requires cultural as well as physical interventions, says Taller Capital.

August 10, 2021

Taller Capital's design for El Represo Colosio Dam and Public Park in Nogales, a city near Mexico's northern border. Credit: Rafael Gamo

In Mexico City, flooding goes hand in hand with water scarcity, creating severe challenges for the capital’s 22 million residents. Architects Loreta Castro-Reguera and José Pablo Ambrosi have spent years reflecting on the condition of water here and elsewhere in the nation. In addition to designing public spaces marked by thoughtful water management solutions, their firm Taller Capital seeks out opportunities to change the popular perception of urban water systems.

The League’s Catarina Flaksman and Sarah Wesseler spoke with them about their work.

*

Sarah Wesseler: Why is public engagement around water infrastructure a priority for you?

Loreta Castro-Reguera: The main reason is that we want to transform the way people relate to water.

In Mexico City, where we live, the basin where the city is situated was once a lake. Although the land has been gradually transformed over the past five centuries, the water’s still here; we don’t see it, but the subsoil conditions and the climate speak of it. We have a very long rainy season that lasts half a year, during which there are frequent torrential rains. Additionally, the city lies over very soft soil that’s saturated with water, because it was once a lake bed.

But at the same time, because of how the city sources its drinking water—through wells that suck water from the subsoil—there’s not enough water in the subsoil to meet our needs, given the rapid growth of the city. There’s a paradox between the excess of water during the rainy season and the profound scarcity we experience year-round. In the past this was a problem only during the dry season, but now we have water shortages all year.

We asked ourselves how we could begin to change this, or at least make people reflect on this condition. And we realized that water has disappeared completely from the image of daily life in the city. Instead, we have an imported, western image of ornamental water—water in fountains or decorative ponds.

José Pablo Ambrosi: A related problem is that parts of the city have sunk more than 10 meters during the last 100 years because water has been pumped out of the soil. We are convinced that the field of architecture needs to take this issue very seriously, because it affects all buildings.

And as architects, we also need to come up with innovative solutions to our water management issues so that we don’t rely only on traditional engineering solutions. For example, one very serious problem in Mexico City is that because of subsidence, many drainage pipes have lost their slope; they’re no longer able to serve the function of carrying away wastewater. When we work on public space projects, we always propose integrating water management solutions into the landscape, into urban design, instead of relying only on hard infrastructure.

Flaksman: Can you say more about the history of water in Mexico City and how things have changed over the centuries?

Castro-Reguera: The most important changes occurred after the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec city located where Mexico City stands today, in the sixteenth century. Before this, the city was made up of small islands and canals, but when the Spanish arrived, they were set on political, economic, and religious domination, and this included the built environment.

In 1680, King Carlos II put out an ordinance that became the Laws of the Indies, which established a code for how the Spanish monarchy should build new cities in America. The code drew on a compilation of urban documents that had been written starting in the sixteenth century. It was based around a grid centered on a paved plaza with a church to the west and government buildings to the east. It didn’t matter if you were building on top of a lake or in a desert or in a forest—you had to follow this ordinance. This way of developing cities took complete precedence over what already existed.

In Mexico City, this style of planning wasn’t a good fit for the environmental conditions. Since the city is in a closed basin, the lake changed levels all the time; in the rainy season the levels rose, and in the dry season they dropped. In the pre-Hispanic era, canals had carried the water away when needed. After the Spanish covered the canals to create streets and squares, the water had nowhere to go, and so the city flooded regularly.

In 1628, there was a huge flood and the city was under water for four years. At this time the government decided to create the Great Nochistongo Ditch, the first major infrastructure developed to drain the lake water from the Mexico City basin.

Late nineteenth- or early twentieth-century photograph of tourists from the United States visiting the Great Nochistongo Ditch, built in the seventeenth century to drain Mexico City's lake water. Courtesy of the DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

After the flood, people were hesitant to move back to the city, but eventually they did, because it was the capital of New Spain. In 1870, frequent flooding was causing problems again, and during the presidency of Porfirio Diaz the government began to take more focused steps to solve the problem. Porfirio Diaz undertook a huge infrastructure project, the Great Desagüe Canal—at that time the largest drainage system in the world. But after 30 years problems started again, and additional drainage systems needed to be built.

In 1960, the problems started getting worse and the authorities built the deep drainage system: a slanted, deep subterranean pipe system. All the lakes started to dry up. There were no longer bodies of water in the basin; little sections remained in Xochimilco and Texcoco. Then the city began to sink, and water stopped flowing naturally out through this deep drainage system as it started losing its original slope. An impressive system of pumps was implemented to help sewage water leave the basin.

In 2006, the last major drainage effort began, which was also the largest drainage project in the world at the time: the Eastern Discharge Tunnel, typically referred to as the TEO, for Túnel Emisor Oriente.

Former Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto (center) tours the TEO tunnel during its construction. Credit: Wikimedia account of Presidency of Mexico (2012–2018)

So it’s a cyclical history of large hydraulic engineering infrastructure. We shouldn’t condemn this infrastructure, as it does work to a certain degree—there is a city of more than 20 million inhabitants built on a lake. But in reality, these projects haven’t solved the problem, because floods always return, and then you have to dig a bigger tunnel. Water never really goes away. We take it out of the lake, but rain is constantly filling it up again.

Flaksman: Can you talk about your public engagement projects related to this theme of water?

Ambrosi: We’ve done several. One, the Eco Pavilion, was a competition we won to create a summer pavilion for the courtyard of the Museo Experimental El Eco. We proposed to simultaneously create a space and generate discussion around the problem of water in Mexico City. What we did was place a section of a drainage tunnel—a prefabricated concrete ring seven meters in diameter—in the courtyard.

To create drainage tunnels, engineers take a huge machine about a hundred meters long into the earth; it has a disk in front that drills the hole, and then these precast concrete sections are placed along it to form the pipe.

So we brought one of these hoops into view and put it in a museum context to create friction with the audience: What are these precast concrete pieces and what are they used for? We wanted to generate discussion about these massive projects the government spends money on to solve problems related to water but that no one actually sees.

Based on this pavilion and our academic research into water at the university, Mexico City’s Ministry of Environment (SEDEMA) asked us to carry out a project dealing with the culture of water. SEDEMA’s goal was just to understand whether putting out public messaging about ways to save water could lead to reduced consumption—it was looking for something along those lines. But at that time, we were starting to work on La Quebradora, a project we did with UNAM, and we were thinking about ways to communicate the benefits of that park to the public. So we wanted to start looking at ways to help people understand that public space could function as infrastructure.

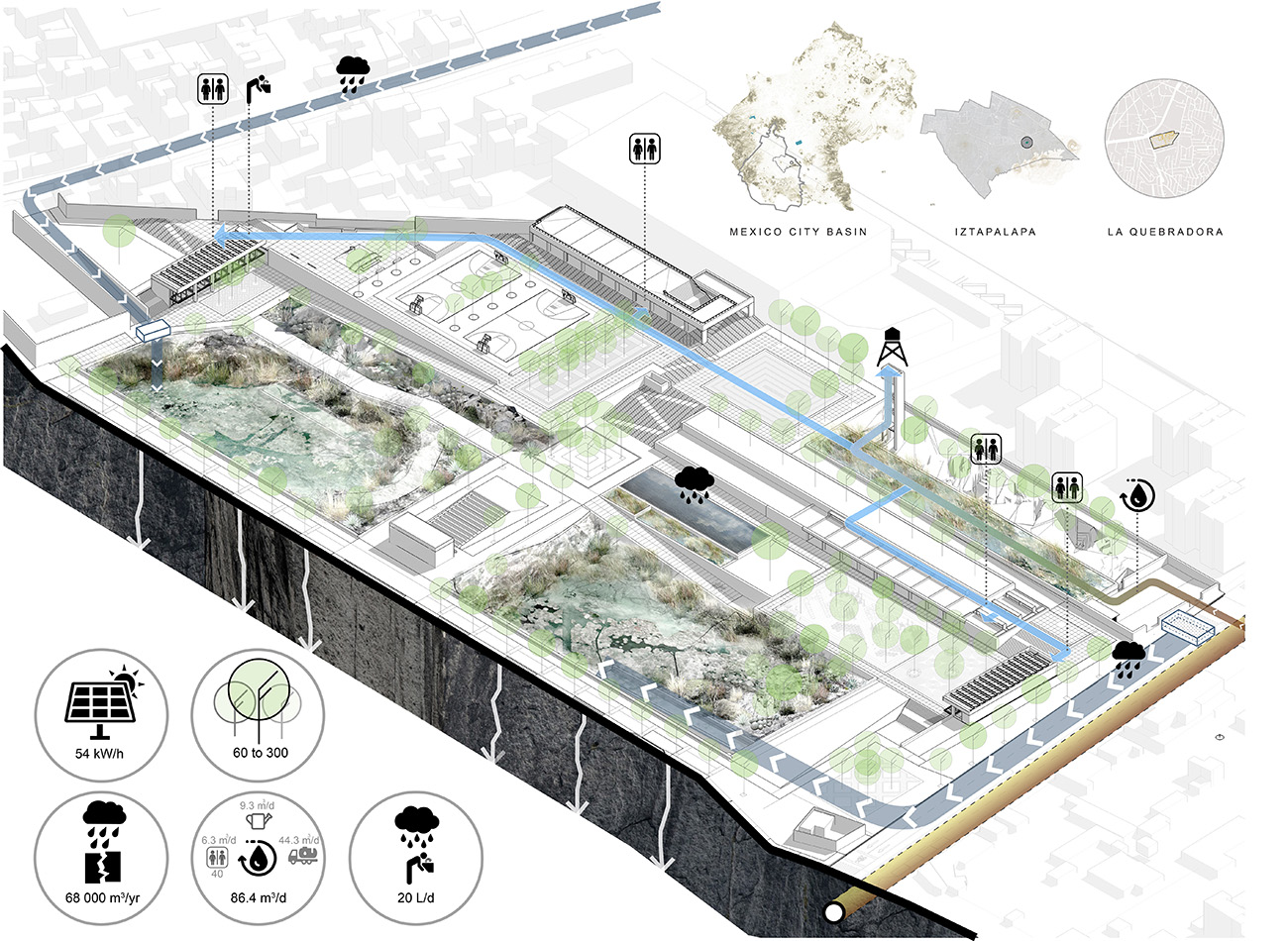

Drawing of La Quebradora, an innovative Mexico City park centered around sustainable water management practices, designed by Manuel Perló, Taller Capital, and a multidisciplinary team from UNAM. Credit: Taller Capital

The campaign the client proposed would have involved speaking directly to residents of one low-income neighborhood and one high-income neighborhood about daily practices to reduce the amount of water they use, such as taking shorter showers, brushing their teeth for less time, etc. Instead, we chose to focus on two public squares, one in Polanco and the other in Iztapalapa, which are neighborhoods with different socioeconomic conditions in different parts of the city. We activated these spaces in order to talk about how public space can link communities while also functioning as water management infrastructure.

We designed a temporary pavilion that could be disassembled and reassembled, using pieces of wood of the kind usually used to make concrete formwork. We set up a 60-square-meter pavilion in both neighborhoods. An exhibition inside told the story of water in the Mexico City basin, explained ways to save water at home, then showed a series of public space projects that work as infrastructure for improved water management. We also included a water catchment element that directed the rain that fell onto the roof into a container where people could go and pour themselves a glass of filtered rainwater.

It was very interesting to see how people responded to the pavilion. In Polanco, which is a very wealthy neighborhood, people wanted to know how the filtration system worked and how you could supply yourself with water like this at home. They looked at the whole exhibition and took their glass of water as if it were an experience. Whereas in Iztapalapa, which is a very densely populated area with high poverty rates, people brought containers to fill with water because they didn’t have any at home. The complexities of the water system weren’t the most relevant thing for them—instead, they were interested in the fact that rainwater could be used to drink.

Represo, another project we developed through the School of Architecture UNAM, is located in Nogales, on the border between the United States and Mexico. The project sits in a basin of an artificial body of water that controls runoff during the rainy season, retaining part of the water that falls there to prevent flooding downstream. But it was in terrible condition when we started working there, with the dam curtain damaged and the water-storage capacity greatly reduced.

What we did here was to improve the condition of this infrastructure and the space around it—which had the potential to function as a flood-mitigation zone—and add a park program. When the dam is required to expand in order to accommodate water, the sports and recreational area floods, and when the dam is empty people can use the park.

This wasn’t easy, because people intuitively think that when a place is a site for water infrastructure you can’t use it for recreation or sports. Honestly, water culture is so damaged in Mexico that usually bodies of water are seen as part of the sewage system, and they become contaminated because of poor water quality, and because people dump their trash there. But if it’s a park that also functions as infrastructure, you have the additional advantage that the community will make it its own and take care of it.

Castro-Reguera: These water catchment sites, which is what the dam was before our intervention, are surrounded by informal settlements. Several of these precarious houses were in very vulnerable conditions, built over the dam wall or on the edge of the water.

We didn’t want to take the water out of the site; instead, we wanted to harness the water and make it part of the life of the community. I think one of the most interesting parts of the project is that we turned this whole community toward the water. Instead of the body of water being perceived as the backyard and the garbage dump, it became the focal point that brings together the whole community by means of a series of walkways, paths, fields, children’s playgrounds, and the body of water itself.

And we designed a covered space, completely open on the sides, where people can have dances, do sports, but that also has a portico that becomes both a threshold and a frame to the body of water. So in a way it restores dignity to water, and to people through water—it’s an element that gives them an identity.

Wesseler: How do you see the future of water, and of your own work, in Mexico?

Ambrosi: It’s a difficult question, because it will take the combined efforts of many people to change the culture of water.

But the good news is that governments—particularly in Mexico City, but not only—have begun taking interest in these projects that address more than one problem. They’re beginning to understand that they can invest in public space to generate community and recreational spaces, but also to solve water issues or other infrastructure challenges.

There’s also a huge opportunity to rethink the places where the government doesn’t ever do anything: the informal city, which needs all the services of the formal city, but where it’s very difficult to invest. And unfortunately, most of the urbanized world falls into this category. It’s an issue that needs more attention. And in fact, it’s already starting to happen, obviously. I think architects need to take a more active role, where we’re not only waiting for a client to come and say, “Design this park or that one,” but also identifying opportunities to intervene ourselves. This approach creates the possibility of developing interventions that vertically integrate different kinds of solutions, taking into account infrastructure, culture, urbanism, the environment, and even the economy.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Without Water, There Is No Growth | Cheyenne River

Lacy Maher from the Mni Wašté Water Company explains how a decade-long water shortage hindered economic growth and stopped housing development.

James Wescoat: Climate, energy, and water-conserving design

Landscape architect James Wescoat discusses water supply and other hydroclimatological conditions in major American cities.

Potable water and local power struggles in Honduras

Timothy Kohut reflects on alternative visions for community development in Tegucigalpa.