The Beauty of the Ordinary

Adib Cúre and Carie Penabad reflect on Miami's rich vernacular design.

May 26, 2021

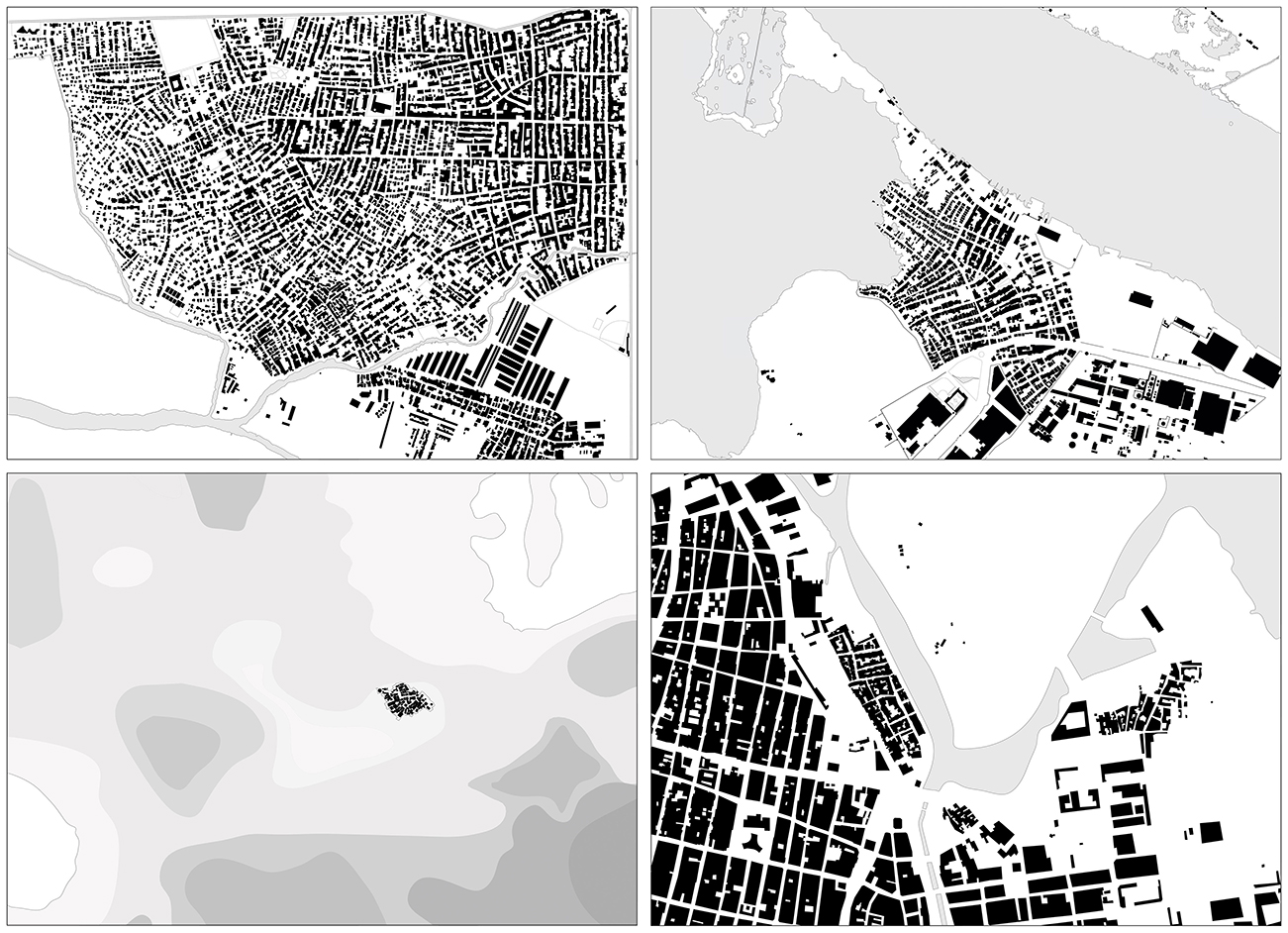

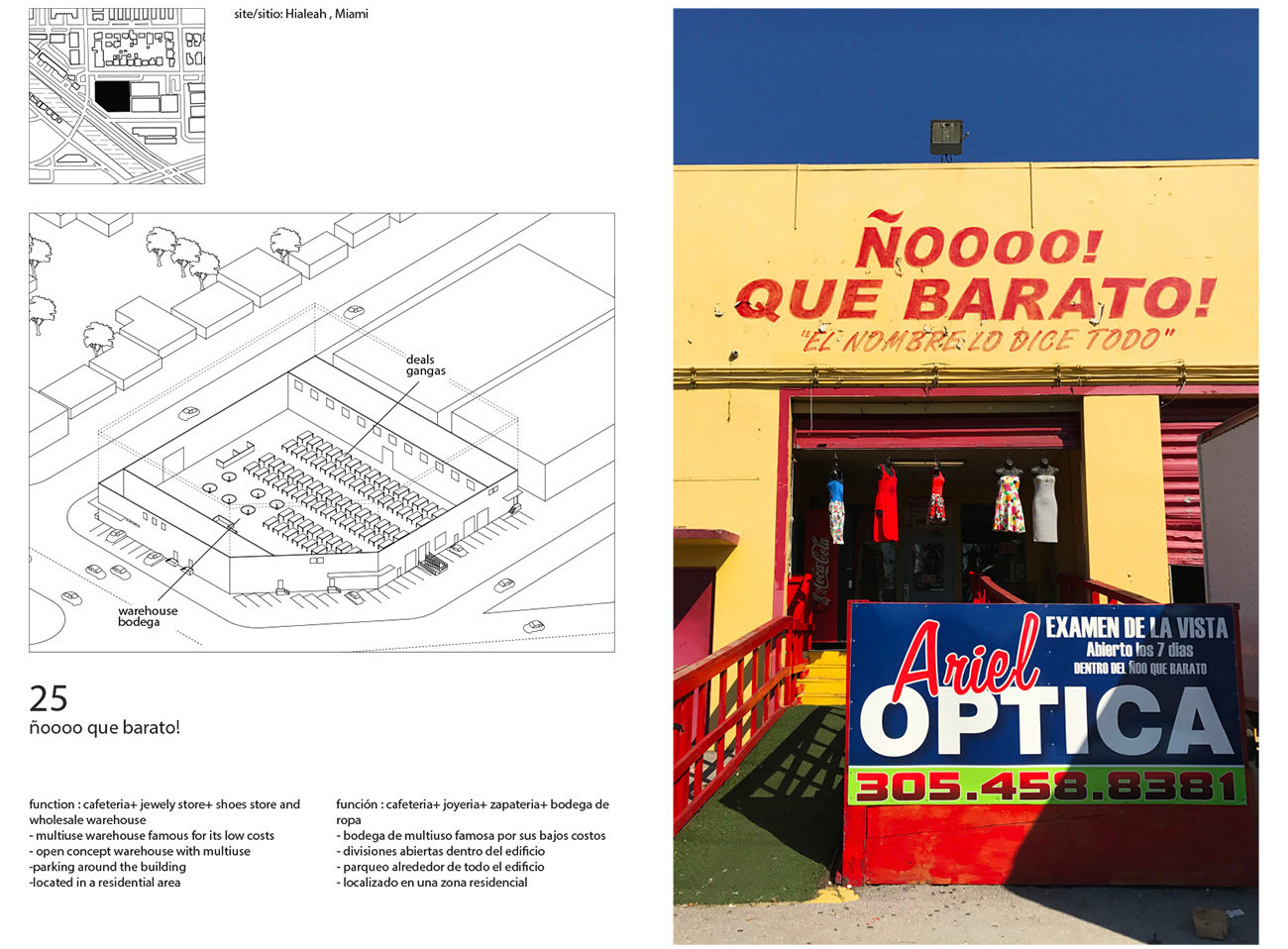

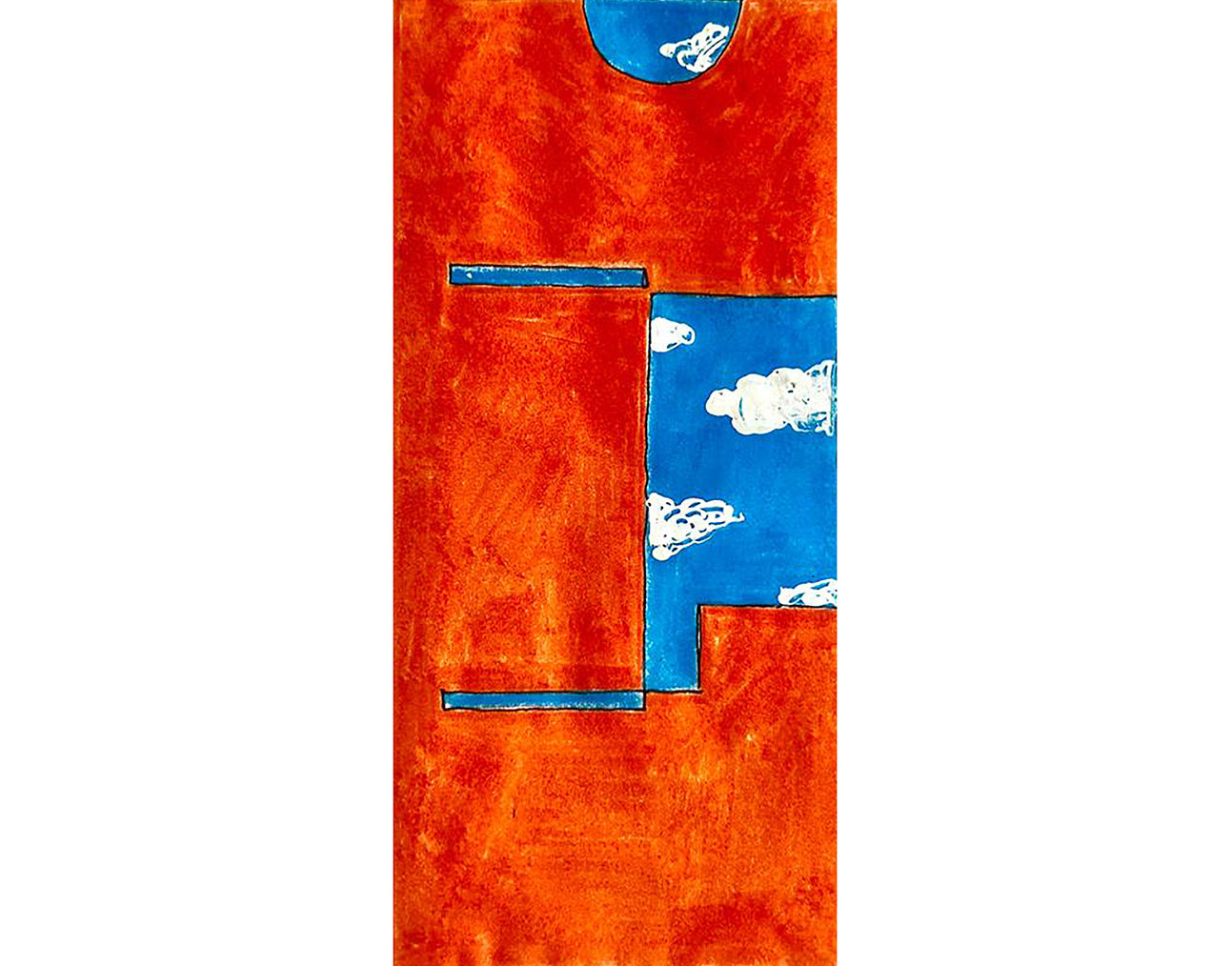

Cover illustration for Made in Miami, a publication and research initiative conducted with students at the University of Miami School of Architecture. Credit: CÚRE & PENABAD

CÚRE & PENABAD’s forthcoming book Made in Miami / Hecho in Miami explores vernacular architecture and urbanism in the firm’s hometown. The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with founders Adib Cúre and Carie Penabad.

*

Can you give an overview of your interest in vernacular architecture and the Made in Miami project?

Carie Penabad: We are interested in an architecture of place; one way that we explore that is through the study of vernacular architecture and urbanism.

Oftentimes when architects think about the vernacular they think about the past: the primitive hut with its thatched roof. But for us the definition extends to contemporary buildings, contemporary cities.

From the beginning we’ve followed a teacher–practitioner model, and a lot of our work takes the form of research that is then applied to practice and vice versa. Through our engagement with the University of Miami, we’ve looked at vernacular, informal urbanism throughout Latin America. We became interested in these places because they’re cities without architects, in essence. We wanted to learn from the wisdom of their urban patterns: their typologies, the way they deal with climate.

Miami also has a lot of informality. It’s not always apparent, because it’s not the image that’s promoted to the outside world, but it exists, probably due to factors like immigration and temporary populations that come in and out of the city. So we decided to look at Miami through that lens.

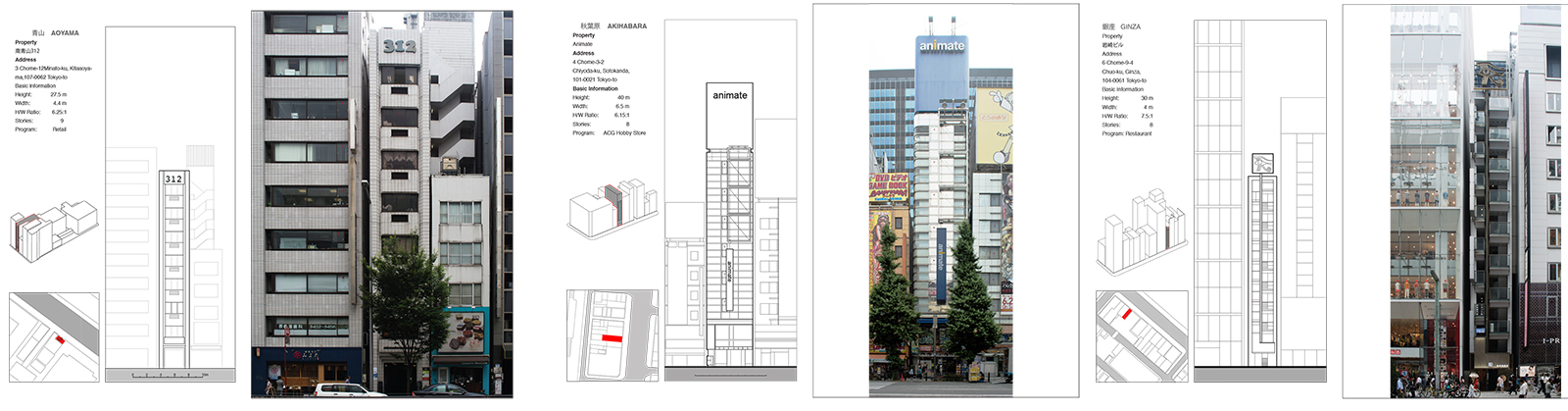

But our research also came about by way of traveling to cities as far away as Tokyo with students. Through these trips, we encountered other local contemporary vernacular examples, such as the pencil building in Tokyo, and came across the book Made in Tokyo, produced by Atelier Bow Wow. This book looks at Tokyo through a prosaic, vernacular lens. We spoke with Momoyo [Kaijima, Atelier Bow Wow cofounder] and said it would be really interesting to explore these ideas in Miami.

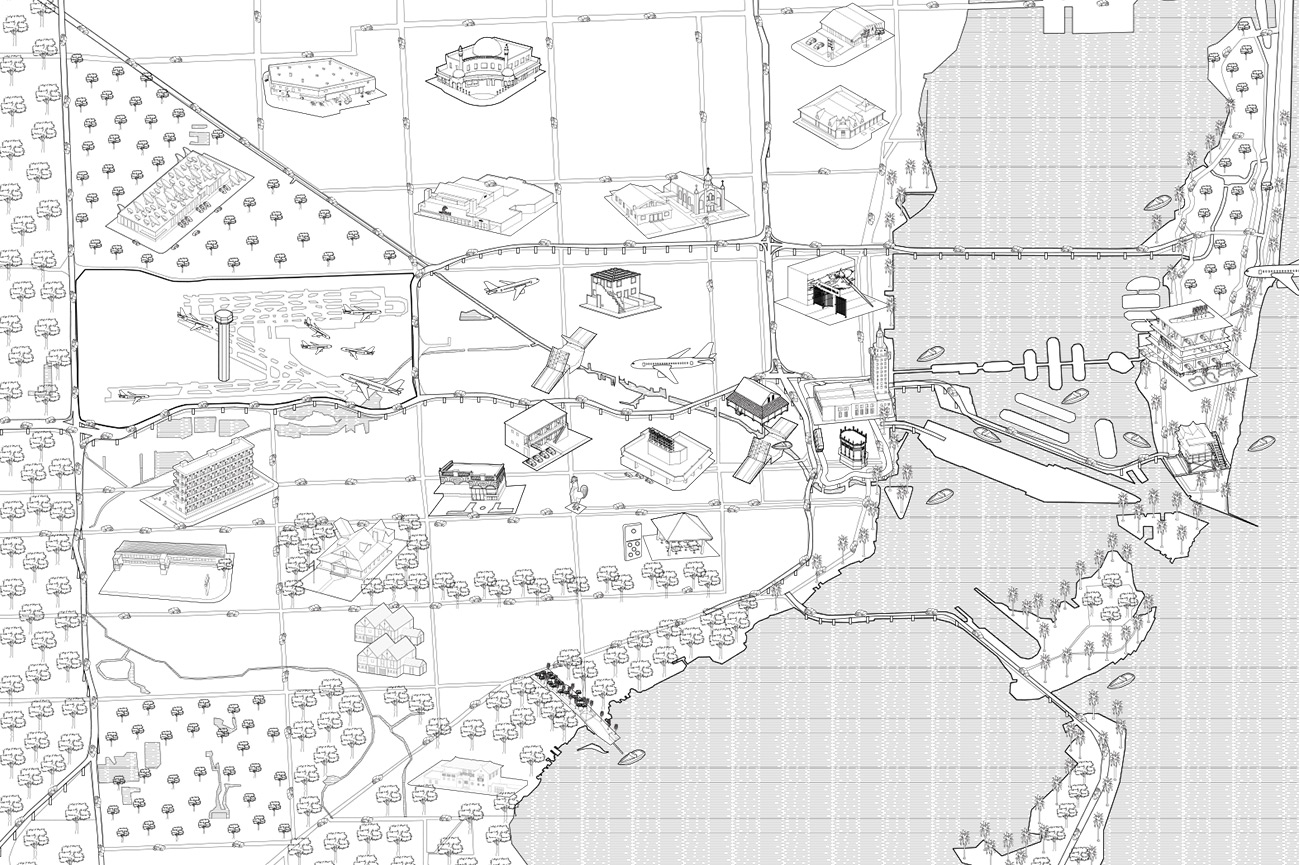

So that’s what we’ve done. We’re now completing Made in Miami / Hecho in Miami. It’s a bilingual guide to the city that examines contemporary vernacular examples that are not architecture with a capital A, but that reveal something unique and specific about this place.

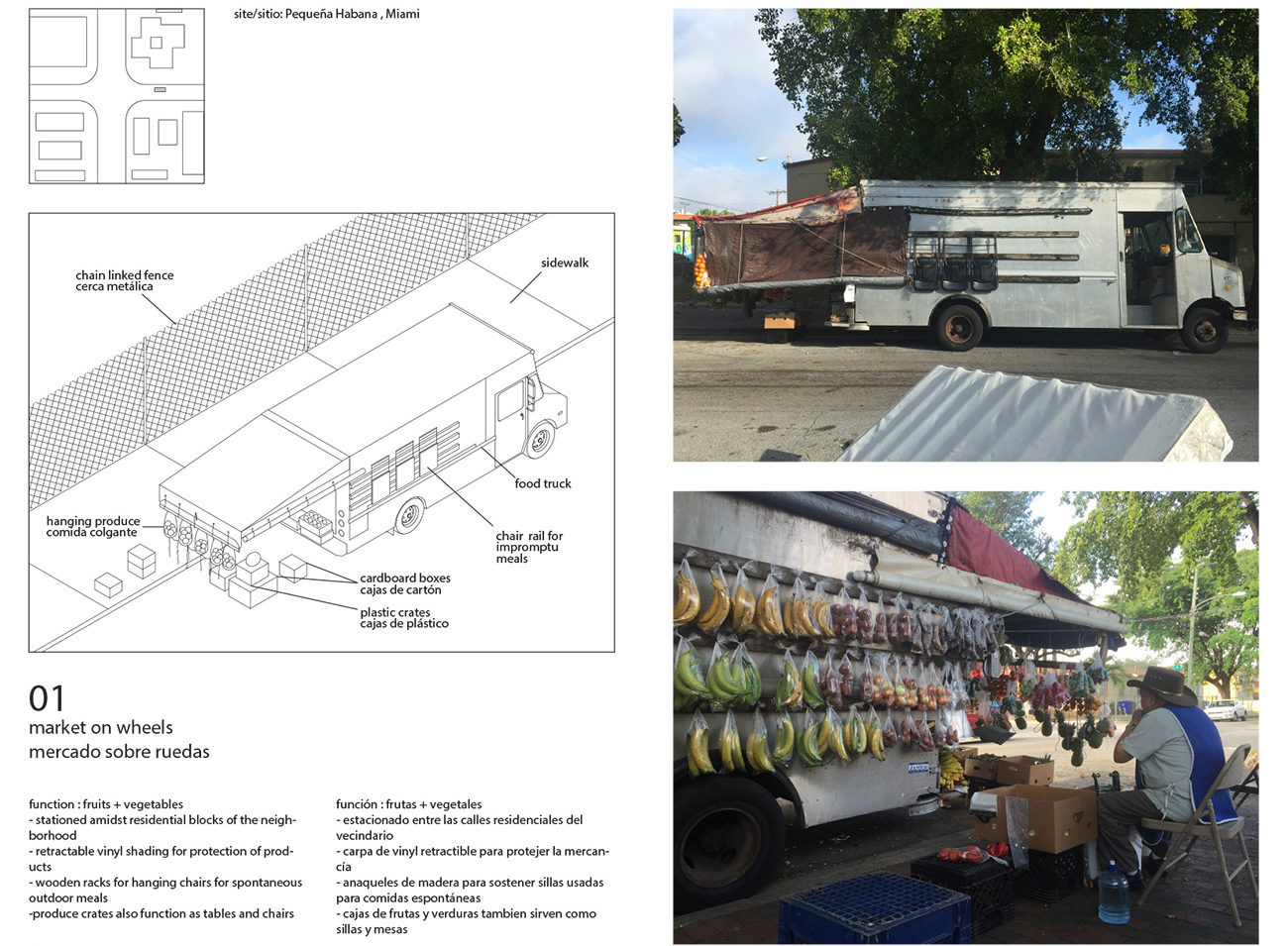

One example we’ve looked at are abandoned gas stations that have been reappropriated. Tenants move in and occupy the space under that large roof and turn it into a fruit market, for example. So all of a sudden there’s communal public space in the middle of suburbia, packed with people eating.

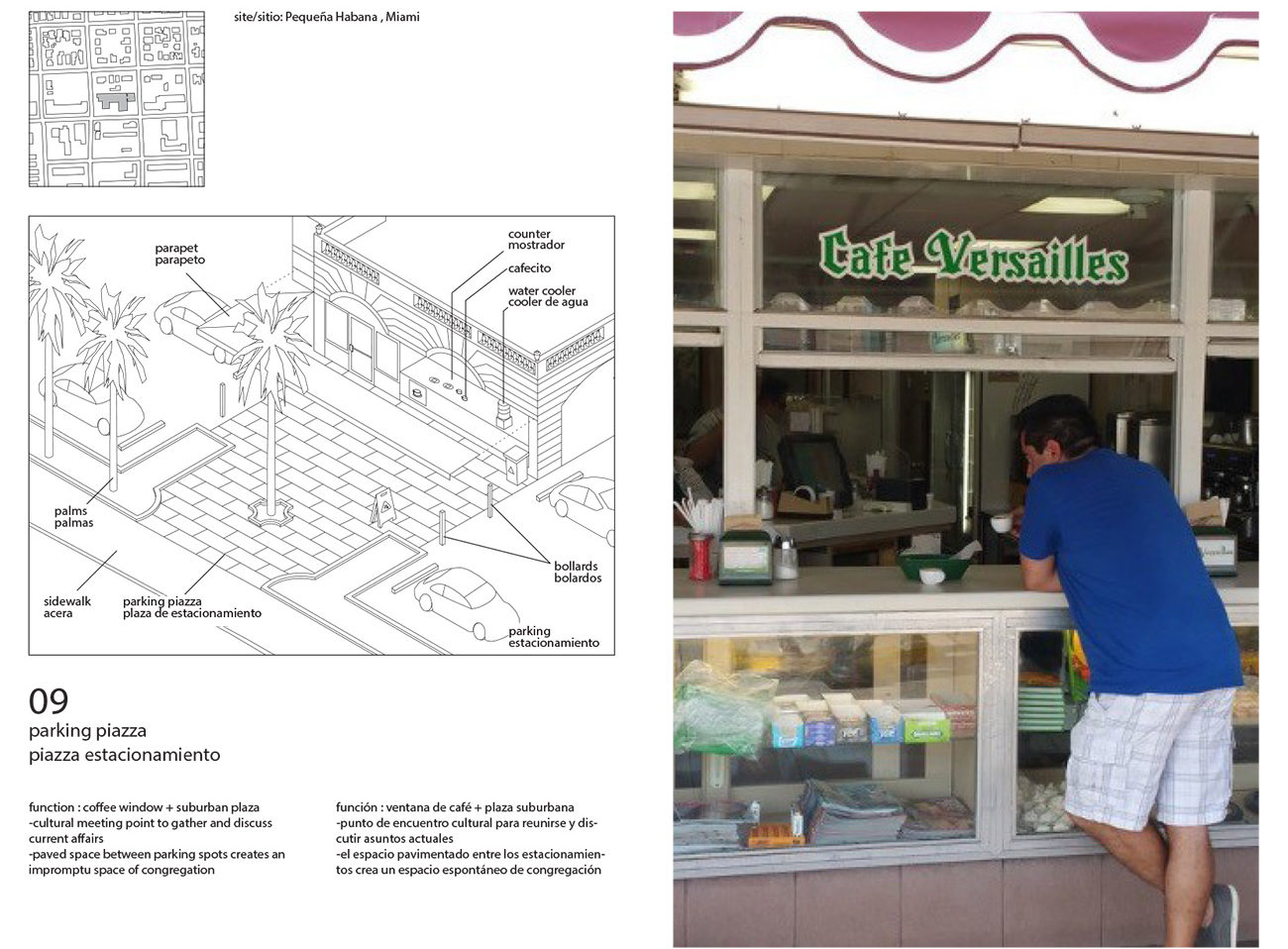

Another example are the Cuban coffee windows throughout the city; people go up to a window—some small, some large—to order a pastry or drink a cafecito. The space in front of the window becomes a gathering space, a type of informal plaza—again, oftentimes in the middle of a suburban landscape.

Adib Cúre: The book is part of our interest in trying to find value in the colloquial or beauty in the ordinary. That’s something that we’ve been trying to do for many years, and it goes back to our own education at the University of Miami School of Architecture, where we had the great fortune of being exposed to teachers who had this interest as well.

Penabad: We don’t turn our backs on high art; in fact, we embrace it. But we also believe that there is wisdom and beauty in the ordinary. And the ordinary can become extraordinary when you start to see how it defines characteristics that make places unique.

How do you think about the relationship between this research and your built work in Miami? To what extent is the book a way to understand urban challenges or opportunities for design, as opposed to a kind of more pure observation or appreciation: See what’s out there first, then figure out what to do with it later?

Penabad: Well, the city is always the initial point of departure for us, in all our work. We trained as architects in undergrad and urban designers in graduate school, and some key figures in our education taught us to always oscillate between the object and the city. Reading places from the macro allows us to see patterns that then inform the way we operate within those worlds.

In the case of Miami, while we do celebrate a lot of what we’ve found, we’re also critical of that reality. The disconnected neighborhoods, gated communities, office parks, and expansive parking lots throughout the city are the byproducts of postwar growth. Oftentimes it’s an inhospitable environment, and it’s not very sustainable. The city has really reached its limits and encroached upon the Everglades; it needs to densify and contract.

In terms of our own built work, MDO is an example of a design project located within one of these typical Miami suburban conditions, adjacent to strip malls and surrounded by surface parking lots.

When taking on projects we ask ourselves, what can we do within the boundaries of this project, both to learn from the site but also improve it? In this instance we did a few simple things. Generally speaking, buildings in this area have parking in the front. It’s a world of vehicles; pedestrians are not considered. We inverted that diagram, placing the building alongside the sidewalk.

Second, the project is in an area dominated by strip malls: very, very low and very, very deep, artificially lit spaces—cavernous, dark spaces. We said, OK, how can we assemble a retail interior in such a way that we create a tall-volume, amply lit space, in sharp contrast to the deep, dark interiors surrounding the site?

We also introduced landscaping—which seems like a small thing, but there are almost no trees on any of these cityscapes. So we thought, well, if we plant two trees that will eventually mature, we could begin to alter the street section.

And then of course there is the building itself, which utilizes the common elements of Miami’s contemporary vernacular architecture—the neon sign, stuccoed walls, prefabricated structural elements, etc.—and composes them in unique and unexpected ways.

All these decisions, while seemingly small, we hoped would produce a kit of parts that would allow at least the immediate area to question the way it operates.

Cúre: Through the Made in Miami / Hecho en Miami research, we’ve also been discovering areas within the city that are potentially extremely powerful sites for the development of housing connected to a very limited but existing metro system. We’ve identified lots and sites that would allow residents to get around without a car, which is the dominant mode of transportation here. We’re beginning to develop housing projects on some of these lots that could become very interesting moments in the city.

This research has obviously focused on the unique qualities of Miami, but I’m wondering if any of the lessons you’ve learned are applicable to other American cities?

Penabad: Well, Miami is emblematic of the challenges of the unbridled suburban development that defined the American city in the postwar era, and in that sense it shares similarities with many other American cities. Miami didn’t invest heavily in mass transit or the public realm. To this day, the public realm in Miami is largely being built by the private sector. Our Oak Plaza project, for instance, is essentially a public plaza that was built on private property. This occurs often here.

Cúre: It’s important to keep in mind that Miami is a very young city, barely over 100 years old, not like New York or Boston. It’s maybe in its adolescent period—learning from the problems and challenges and mistakes made in the last few decades. We believe that’s the case. We’re beginning to see a better city, and a more mature city.

Penabad: We do see that the city is making wiser decisions in the sense that it’s densifying the city center.

Although now Miami has even greater challenges because of climate change. We are among the most vulnerable of cities, really; we’re ground zero. I can’t say definitively that Miami is leading in terms of cities that are challenged by these issues, but it is doing interesting things.

One thing that we have discovered is that Miami only has housing at two extremes, for the most part: we have detached single-family residential and the high-rise condo building. There’s virtually nothing in between. And as a result, we have pockets of extreme density and wealth, and then we have a kind of flat landscape that moves us into very vulnerable territory.

We think there’s a need to develop new housing prototypes for Miami. We are currently working with ĀINA Sustainable Housing Development to design new urban models that will allow you to contract into higher ground in the future and develop a city in the middle ground: a mid-rise city that could allow us to foster more sustainable neighborhoods for the future—more sustainable both architecturally and socially.

In trying to rethink housing or other aspects of the built environment in Miami, do you find it easy to identify collaborators—developers, clients, etc.—who share your vision, or is it a struggle to convince people to try something new? And what about the regulatory side of things? Do building codes and the like allow for experimentation?

Penabad: We have found common ground with individuals and corporations that seek a greater good beyond the immediacy of their own projects. Our recent work with ĀINA Sustainable Housing Development is investigating how we can make affordable housing—truly affordable—in the city. Why can’t affordable housing be beautiful? What does that mean in Miami, and what kinds of regulations do we have to be able to push back on?

We chose to develop these ideas at a smaller scale with a team that is willing to, quite frankly, go the extra mile. Whenever you want to question the norm, you really do have to put a lot more time and effort into thinking how you can push back against certain conditions that create what you’re seeing around you. That involves more design time and more commitment, but we always think it’s worth it, because if you can create one project that illustrates a different way of doing things, that can become a new model. It helps others see a different reality for a given place.

Cúre: One thing that is also happening is that some of the codes are changing—perhaps an example of how Miami is growing and maturing. The City recently changed the code to allow for different densities, different building typologies, different modes of living and working. In some cases, developments don’t require parking, or as much parking as before. So the City is trying to imagine a community that is much more connected to public transportation, less reliant on the car.

In the end, we’ve been fortunate enough to work with clients that are interested in the shaping of the city, and we have worked closely with them to provide new places and spaces for Miami.

We believe that being collaborative is an essential part of being an architect—it’s this messy business of negotiating and working things out, and we’re very comfortable with that. We believe it’s actually fundamental to what we do: collaboration with clients, collaboration with the craftspeople that build the buildings, collaboration with engineers, collaboration with senior officials—trying to figure out intelligent ways of producing better work and building the city of the future.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

The spectacular vernacular of Queens

Two photographers discuss the beauty, joy, and whimsy of the “ordinary” houses of Queens.

Drawings and intent in American architecture

Excerpts from the book's introduction by David Gebhard looks at themes of style, intent, and value in architectural drawing, situating these works in relation to "high art" of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Mira Hasson Henry: Gentle nudge, cutting look

Mira Hasson Henry of (HA) Henry Architecture tackles ideas of cultural identity, normativity, and the vernacular.