On the table: Dinner with Fernanda Canales, Ersela Kripa, and Stephen Mueller

Three designers recognized in the 2018 Emerging Voices competition join members of the design community for a broad-ranging conversation.

The League’s annual Emerging Voices program recognizes eight firms with distinct design voices. In March and April, each firm delivers a lecture, then joins prominent architects, critics, and others in the industry for dinner and informal conversation.

In the following, Mexico City-based Fernanda Canales and El Paso-based Ersela Kripa and Stephen Mueller, founders of AGENCY, discuss borders, time, and political engagement.

Sunil Bald, studioSUMO: As I was listening to both lectures tonight, I was thinking, what is the other lecturer thinking? It was so interesting to have AGENCY coming from the border, and then Fernanda coming from the other side of the border. What from the other talk resonated with each of you?

Fernanda Canales: In Mexico the border is a recurring theme, but in Mexico City, we’re always speaking about it from a distance. I find it really appealing to actually make your life in that place.

I also really envied that for AGENCY there’s no division between research and production, books and teaching. I have to divide my time between writing and seeing clients and rushing to the construction site.

Ersela Kripa, AGENCY: I was thinking about the shared interest in empowering laborers, in the democratization of making. There’s a shared idea about respecting and enhancing the work that’s made by people who might not always necessarily understand architectural drawings, but understand the logistics of making.

Bald: That’s an issue where you intersect in an interesting way. AGENCY’s work looks super high-tech but is actually pretty low-tech. Fernanda’s work is so carefully crafted and beautiful, but is made by rural laborers who don’t look at the drawings.

So in both cases, the active making is not necessarily a preconceived operation, but instead really takes advantage of limitations. When you work that way, are you surprised by the results?

Canales: I try not to be. We were just speaking about the equilibrium between controlling and improvising. We have to deal with that all the time in Mexico because of the disparity between the designs you’re taught in school and the actual realities of building.

My work attempts to learn from construction workers and adapt projects to existing conditions. But I hate surprises in the sense that if a project loses its character or priorities, it’s no longer yours.

Stephen Mueller, AGENCY: We talked a little about the benefit of constraints in our lecture, but paired with that is the idea that designers need to identify what’s achievable and how to bring the most dignity to the situation given the limitations.

That was one of the things that struck me about your work, Fernanda: You’re so focused on the achievable effects within the reality of the material conditions, the labor condition, the geographical condition of the site.

Dominic Leong, Leong Leong: Along those lines, I think what’s interesting about every architecture practice is that they have their own concept of time and control. That’s an increasingly interesting thing to think about relative to our contemporary context, when things seem to be constantly accelerating vis-à-vis technology.

In your practices, do you feel like you’re trying to catch up or slow down relative to time?

Mueller: I have architect friends who describe their practice as trying to operate five minutes into the future. I feel like we tend to take that sort of tack, but our research is based on what’s happening now in order to predict what might happen soon.

Our built work has all been done very expediently, though—a 24-hour installation, a three-day installation. We see them as prototypes or rehearsals of a future that we might be helping to make concrete.

Leong: The other commonality is that you both have not only a making practice, but also a mapping and research practice. I’m curious how those two different types of practice have different senses of time embedded in them.

Canales: Yes, research and writing has its own timing, and it’s very different from clients and buildings and competitions.

For me, doing both things is the only way to have some sanity. I think we cannot produce without thinking, and cannot think without producing. My interest is not in history as a thing from the past, but as an active instrument to better understand the present.

Elaine Molinar, Snohetta: Fernanda, your work displays a very strong singular architectural vision. I’m wondering what role the client plays in that.

And Stephen and Ersela, have you thought about how to bring your work to a general audience?

Kripa: It’s a great question, and it gets back to this idea of time, where the larger research is simmering in the background and the smaller projects are… well, if we’re on a train of mapping, the stops are the small projects.

Even temporary installations can generate a public space for discussion—having 2,000 people inhabit our selfie wall and have a discussion about data privacy, for instance.

We do have an enormous private client project right now. It’s a city block in El Paso, and we’ve been really lucky to cultivate a relationship with an incredible client. We looked at a property and imagined ideas for it, and then we spoke to this person and he absolutely loved the proposal and bought the property. It’s been successful because the person we partnered with believes in it and we have a lot of shared interests.

Canales: I used to find working with clients really challenging, especially with public work. The administration changed and everything fell apart, or competitions never respected the actual project…

But now I’m trying to shift the scale of my work. I’ve never had an office, but I thought I needed to have a big team and a big office and do a lot of competitions and projects. Now I’m slowing down and shrinking, even in the idea of how many projects can I do in a year, or in a lifetime.

That really helps, because clients are no longer a struggle or fight. It’s just a dialogue that has its own timing and its own process. It’s part of understanding that I have to be on the site more, narrowing the gap between client, site, and construction workers.

Ken Smith, Ken Smith Workshop: I was struck by the emphasis on expedient and tactical operations in both firms. But at the same time, the practices are strategic and ideological. How do you negotiate between the two?

Mueller: I think the strategy is played out in the selection or crafting of the project. There are projects we’ve chosen not to pursue because they didn’t fit in with our stance. And the tactic is basically a method by which we engage when we choose to.

Canales: I have no idea, actually. It’s my everyday struggle—what to say yes to, what not to do, how to make something work when you’ve been doing it for two years. Most projects take longer than I think. And being halfway through and not being able to develop it in the way you imagine it is really problematic, but once you start there’s no way out. It’s a matter of hanging on and fighting for the original ideas to come out.

Rosalie Genevro, The Architectural League of New York: A question for AGENCY. As faculty [at Texas Tech in El Paso], yours is a fairly unusual situation, given your binational student body. What do you dream of for your students? What kind of future do you imagine for them?

Kripa: Our students are absolutely incredible. The issue is that because they live this binational condition—some of them cross the border from Juarez almost every day to study with us—they don’t necessarily have the time or tools to understand how unique and important that condition is.

El Paso is one of the major ports that enacts the NAFTA agreement: Trade moves from Mexico to Canada through the US there. But there’s so much political and economic activity that completely ignores what’s actually happening.

After the election, most of the students were really upset. Some of them were crying and saying, “I don’t know how to be in a country that doesn’t want me here.”

Now, instead of living with this marginalized psychology, they’re doing research that proves how important they are and how important their context is. Through rewriting curricula, studios, and seminars, we’ve been able to help them understand that they actually are at the center of the world.

They’re generally first-generation students, and they don’t necessarily have mentors in their immediate context, so we’ve become not only their teachers, but their friends and mentors.

Mueller: Yeah, a lot of students come to us with a perception of being at a disadvantage, and we want to transform that. They are actually uniquely situated to make a difference.

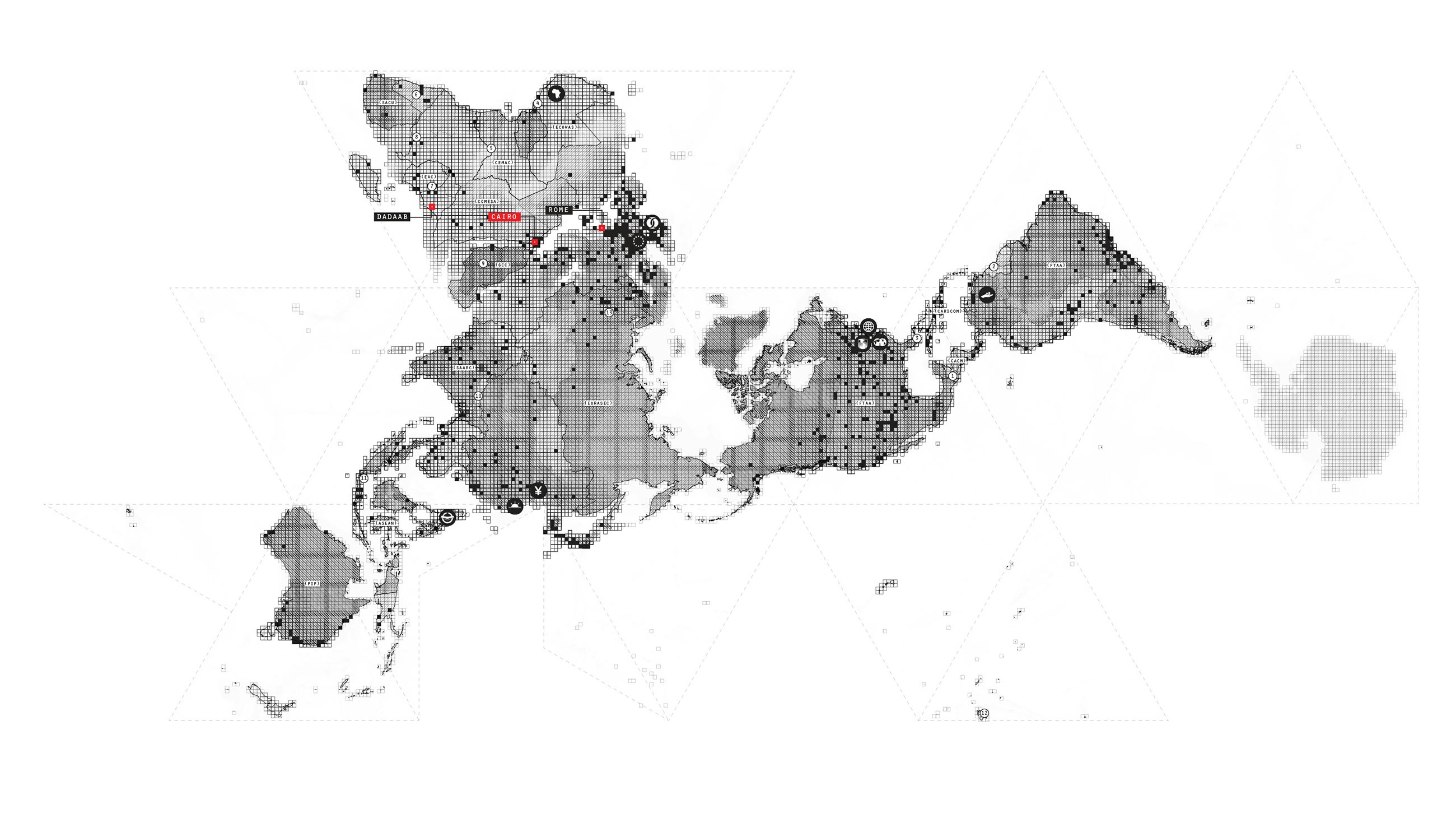

Border wall dividing Anapra, Mexico, from New Mexico. AGENCY is planning to deploy dust sensors in this area, which is on the outskirts of El Paso. Credit: AGENCY Architecture LLC

Bald: Question for Fernanda. We were looking through the Emerging Voices portfolios—I’m the only one here from the jury, but we look through all the applicants’ portfolios—and then we have this incredible two-volume version of the history of Mexican architecture over the last century that Fernanda wrote. It was like, damn! How the hell do you do all these things, especially since you don’t have an office?

And this is a selfish question, because my partner always thinks about the integration of research and practice, whereas I think I’ve always seen them as parallel. I’m hoping that there’s some kind of affinity here, that that’s how you operate as well.

Canales: I think I can do both because precisely I don’t have an office. I used to be really ashamed of not having an office, but now I think it’s what allows me to understand the different timings and to focus. Sometimes I don’t have work, so I have more time to write. Sometimes it’s the other way around.

The two things also complement each other. For me it was a necessity to do both. At the beginning of my career I thought that if I designed many bathrooms and closets very well, one day I would design a house. And after doing bathrooms and small apartment renovations for 10 years, when I told people in Mexico that I had studied architecture, they always said, “Oh, so you like curtains and sofas!”

So it was really important to start this academic work and convert my career into a whole new thing—not just interiors. Now I don’t know how you can do one without doing the other.

Bald: With this perspective from your research, do you feel that this is a special moment in Mexican architecture? Do you feel that your generation is unique?

Canales: I think there have been many special moments, but this one is different because architects are coming abroad more and there’s more of an international connection, at least with the United States. This is really recent. Most of the architects in my generation are giving classes in the United States, so there’s an opening that was not common in the past.

But no, I think every generation has its own power. I’m now more interested in the newer generation that I barely know. None of us are as prepared as they are, and their understanding of Mexican architecture is fascinating.

Leong: To add to that, we were talking earlier about how you started your lecture with the image of Mexico City in 1968, when there was alignment between the political administration and urban development, and the architect was valued as an active participant in the formulation of the city.

We’re in a radically different place today. I think this also speaks to this conversation about strategies and tactics. There is a radical misalignment between political agendas and architecture that produces a different expectation of what it means to be an architect, as well as a set of strategies and tactics that we have to develop in order to negotiate that misalignment. I see that happening in both practices.

Mueller: Yeah. One of the misalignments that we’re exploring is the relationship of architecture to military engagement. There are historical examples, right? Leonardo da Vinci—all these historic alignments where architects have trodden very deeply into the structures of building and militarism.

So we recognize that there is this inherent misalignment between these historic roles, and there should be an even more radical misalignment moving forward. But to disengage would be a mistake. So we intentionally engage in order to reclaim a seat at the table for the architect.

Canales: For many years, and particularly around the 1950s, the Mexican president commissioned museums and public work in a time characterized by a really tight relationship between power, institutions, and architects. And we’ve lost that.

In many ways that’s a good thing—architecture has been democratized—but in Mexico we still don’t have the institutions that can provide truly democratic commissions. We’re lacking the old system, and we don’t still have the foundations of the new one.

So I think improvisation—working abroad; doing things that nobody asks for, in a way—is our way of finding new alternatives so that we can be useful to society. Society in Mexico doesn’t need architects to build, so we’re really fighting against the system.

Text edited and condensed.

Explore

Frida Escobedo, Taller de Arquitectura lecture

Escobedo explores the concepts behind projects in Mexico, the US, and Portugal.

On the table: Dinner with Eduardo Cadaval, Clara Solà-Morales, and Thomas F. Robinson

Emerging Voices winners discuss timber construction, architectural ethics, and the value of design.

Rahul Mehrotra: Working in Mumbai

Rahul Mehotra discusses his research and design practice.