Interview: SITU Studio

The Brooklyn firm combines design, fabrication, and research to explore a broad range of spatial issues.

Emerging Voices 2014

SITU Studio

Basar Girit, Aleksey Lukyanov-Cherny, Wes Rozen, and Bradley Samuels

Basar Girit, Aleksey Lukyanov-Cherny, Wes Rozen, and Bradley Samuels founded Brooklyn-based SITU Studio in 2005 as an interdisciplinary practice that seeks “new territory for the designer’s role in politics, science, society, and the environment.” Organized into three divisions — design studio, fabrication, and research — the firm engages a wide range of spatial issues by leveraging “fabrication efficiencies, material re-use, flexible assemblies, and community involvement.” Recent and current projects include the Maker Space and Design Lab for the New York Hall of Science in Queens, the ReOrder Installation in the Brooklyn Museum Great Hall, and Heartwalk, first installed in Times Square and subsequently relocated to DUMBO, the Rockaways, and then permanently to Atlantic City. Among the firm’s applied research and spatial analysis projects are the Trezona Fossil Reconstruction with Professor Adam Maloof of Princeton University and the UNSRCT Drones Inquiry, a data visualization effort in collaboration with Forensic Architecture and Professor Eyal Weizman of Goldsmiths, University of London. In March 2014, on the occasion of their Emerging Voices lecture (video embedded below, also available here), the four partners sat down with League Program Director Anne Rieselbach to discuss their practice.

Anne Rieselbach: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Brad Samuels: Having four partners with varied interests, skill sets, and talents has shaped the voice of the studio. We have known each other a very long time and went to school together at Cooper Union, so we’ve had this formative experience of studying and exploring together that we’ve translated into a practice and a business model. On the one hand, our voice is quite diverse, and on the other hand, it’s very coherent because of that history, that arc.

Wes Rozen: I think we have a curious voice. We seek opportunities to engage in dialogue with collaborators or with new materials as often as possible. We take an open approach to each project we do, and we start with a lot of questions rather than a fixed idea.

Basar Girit: It’s also about a process of discovery and experimentation, in materials and structures. We always want something unique to emerge that users can interact with in a different way.

Rieselbach: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practice in today’s economic, professional, intellectual climate?

Samuels: I think the intellectual and technological climate now is prime for redefining the field. The understanding of “the discipline of architecture” that has dominated the discourse for so long is less and less relevant to contemporary practice. I think there’s a lot of openness to rethinking what we call spatial practice, more broadly defined — partially out of economic necessity and partially out of an increasing porosity between disciplines. I think there’s territory that designers can explore and contribute to that somehow we haven’t participated in previously.

Girit: Our model from the beginning has been to work in a variety of ways. Our research and fabrication divisions allow us to get projects that are not architectural in the traditional sense. I think that model really helped us through the recent economic recession.

Rieselbach: You founded your firm while still students at The Cooper Union, and have worked together now for almost a decade. What drew you to independent practice at the start of your career?

Aleksey Lukyanov-Cherny: The economic climate at the time, in 2005, was very favorable for beginning our own practice. Work was coming in and it was easy to get jobs. That would not have been possible three years later, so we lucked out.

Rozen: We set up an infrastructure that allowed us to work in the ways that we’d become accustomed to as students. That is, by making and by iterating ideas through physical manifestations, in a workspace that was evenly balanced between a digital studio and a workshop.

SITU workshop | Courtesy of SITU Studio

Very quickly we had to figure out how to pay rent and get the resources we needed to build up a studio, so we evaluated our skill sets and decided that we had to take a wide approach to what we’d consider for projects. This ended up being great for survival through a difficult economic time, and it opened up dialogue with other offices and other fields.It was great to come out of school and work with several different offices rather than taking a singular approach to making architecture.

Lukyanov-Cherny: We studied together through five years of education, and we set up our own little shop and studio two years prior to graduating. We’ve had this home base for a long time, and we got used to independence. To disband after those five years, and those two years working together, did not feel right to us.

Girit: It didn’t even seem like a question. While not an official company, we had already formed a workshop and were collaborating on creative building projects, even bringing in some money. We just continued and at some point decided to incorporate to make it official.

CNC milling in SITU’s workshop | Courtesy of SITU Studio

Rieselbach: You fabricate work both for your own commissions as well as for other architects. How did this aspect of your practice emerge? Are there any surprising lessons from fabricating other architects’ designs?

Samuels: It emerged because it was a viable business model and a way to stay solvent after graduating. There was a technological niche to be filled at that time in terms of competency in digital and physical work flows.

Rozen: We adopted CNC routing and 3D printing early on, at a time when those were still fairly new and people were beginning to discover the possibilities. These technologies were a great way for us to establish our fabrication practice and build clients and contacts.

Girit: While the fabrication work we do for other clients isn’t our own creative work at a conceptual level, there’s still engineering and material experimentation happening. And that’s always useful.

Rozen: We’re taken into geometries and territories that we might not naturally go toward ourselves. It’s an active pull away from our tendencies as designers, and we are forced to really think through alternative models for making architecture.

ReOrder installation at The Brooklyn Museum (2011) | Photo by Keith Sirchio

Rieselbach: How, in practice, does the tripartite organization of your firm — studio, research, and fabrication — work? How has each aspect of the practice informed the other? What are the roles for each partner?

Samuels: I’ll back into that question by saying that the divisions were really an attempt to clarify for the public our different types of activities. Internally, while we can’t all be involved in all projects all the time, there’s a tremendous amount of discussion and debate across all three divisions.

Girit: Creatively, we see it as one entity with structural and organizational divisions. As partners, we’re involved in all aspects but we manage different aspects of the business.I lead the fabrication aspect, Brad leads research, and Aleksey and Wes lead design. Yet even within those leadership positions, we are all involved in the larger decisions and operations.

Heartwalk public art installation in Times Square (2013) | Courtesy of SITU Studio

Lukyanov-Cherny: The partners rotate throughout, so that two partners may be working on a couple of design projects while two others are doing some of the fabrication and research work, and then we’ll switch around. We keep the creative work rotational, but then there are administrative roles that we all have to play, such as marketing and PR.

Rozen: There are two modes of operating: either the three entities are split and we present just one entity at a time, or we fold all three together and can offer turnkey projects. At different times we need each mode. As designers, it’s great to present a project and be able to back it up with fabrication expertise and research experience. For instance, our experience working with scientists is certainly appealing to the museum sector. The clients that understand what we’re able to offer across all three divisions really appreciate this diversity.

Samuels: The trajectory of the practice is moving toward buildings and projects with increased complexity and scale. Those weren’t the projects that landed on our doorstep when we were right out of school. Our interdisciplinary work and fabrication work informs how we approach those larger projects.

Sandbox at the Design Lab of the New York Hall of Science | Photo by John Muggenborg

Rieselbach: You’re building a Design Lab for the New York Hall of Science, which seems like a remarkable fusion of all three areas of your practice. How have the design process, fabrication, and installation come together?

Samuels: There is a certain uncanny affinity between the values of the institution, and their ambitions for rethinking science education to engage kids who might otherwise be uninterested, and the ethos of our practice. They teach science through design: asking visitors to problematize scientific principles, determine design solutions, iterate, and document their work. Instead of presenting the great canon of scientific achievements, the museum puts on display every solution some kid made before you. It’s a new model of learning that is all about making, and the feedback between making and design. That really speaks to us as a practice, and our reasons for setting up our studio and fabrication practice together. The program and the philosophy are really aligned even though they’re a science museum and we’re a design studio.

Lukyanov-Cherny: The Hall of Science was very invested in the making process itself, because that’s at a core of their teaching principles. I’ve never seen clients go so wild over a weld, or the kind of bolt used in an assembly. Having that level of appreciation from the client is refreshing and makes our job easier and happier.

Girit: We approached the process as a miniature design experiment, in which we had the space as a whole and then five separate projects within it as these exercises. The whole process was one of making — whether drawing or model making or building, it was this constantly emerging process, similar to what happens in the maker space itself.

Design Lab at the New York Hall of Science | Photo by John Muggenborg

Samuels: It taps into maker culture and what happens when you codify an already robust community into a more institutional context. We wanted to celebrate materiality, detailing, and structural logic. The design exposes the structure as part of the language of the project, becoming a symbol for everything that happens and is encouraged in that space. It was a welcome opportunity, since structure and detail often are buried or hidden behind sheet rock at the end of a project.

Rieselbach: How did SITU Research come to be? How do these eclectic research projects come into the office?

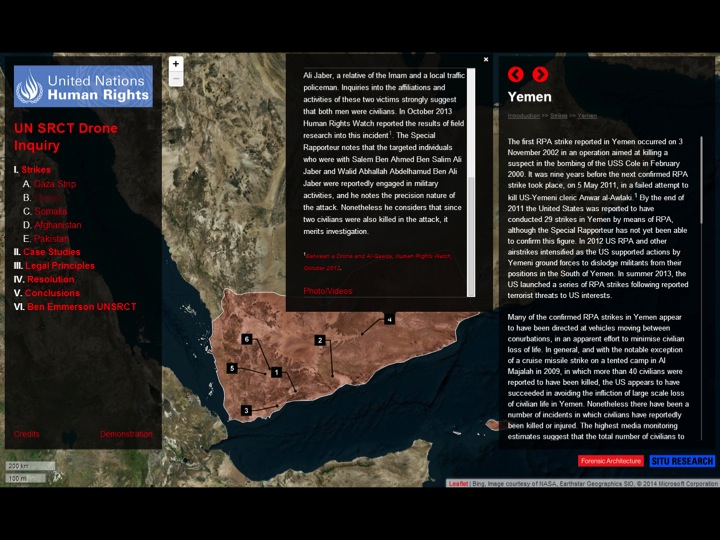

Samuels: SITU Research came into being to provide a context for projects we had been doing since the inception of the practice. Spatial analysis as a way of revealing or even advocating for social and political change has long been a theme in our work. But it started to become harder for the outside world to understand a project about a human rights violation next to a pavilion of some sort. The insertion of SITU Research as an official division was an attempt to put them in proximity, but not create a hierarchy between the subjects.

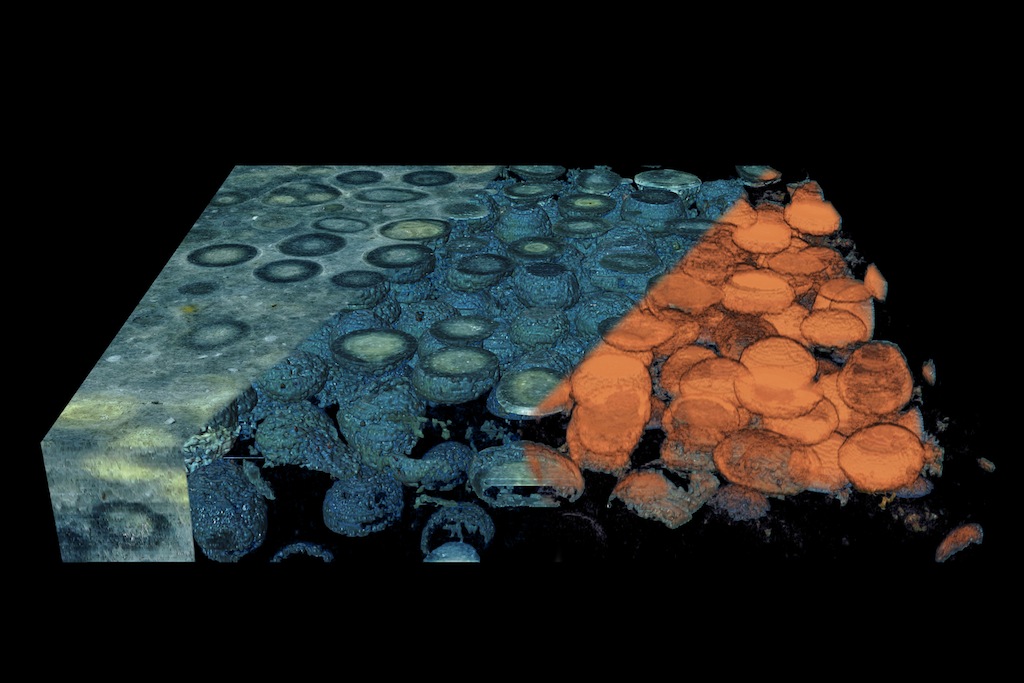

The research projects are at scales that are different than the architectural scale. The geology and earth science projects, for instance, are collaborations with people who fundamentally are asking spatial questions but on either microscopic or large geographic scales.

GIRI project colored 3D rendered mesh using Voxel data | Courtesy of SITU Research and Professor Adam Maloof

These projects come to us through both happy accidents and through intellectual engagement, as generally curious people who don’t look to sequester ourselves in a disciplinary silo. The fossil and meteor crater reconstruction projects happened through informal conversations with interesting people, during which we identified an overlapping need.

What we don’t explicitly appreciate very often is that we’re free of institutional pressures and the conventions of how research is conducted. None of us are trying for tenure or worried about our next peer-reviewed paper right now. Our friends and colleagues working within other institutions are under tremendous pressure to work in a certain way, and our lack of pressure frees us up to do research that might not otherwise get done.

Interactive visualization for the UN SCRT Drone Inquiry | Courtesy of Forensic Architecture and SITU Research

Rieselbach: What does the methodology and overarching vision of an architect bring to a social or scientific project?

Samuels: Architectural methodology brings a way of working focused on orchestration and identifying applicable tools to solve a problem. In other words, we’re generalists. In some cases, the tool that makes the most sense might be a fairly esoteric remote sensing technology; in other cases, it might be an attempt to draw a space based on a narrative account from someone’s memory. All of that is within the spectrum of what we do as architects. As an analog, an architect doesn’t design all of the HVAC in a given building project, but he does coordinate the system and how it feeds back into the design. That same architectural skill set is applicable to spatial practice research.

Rieselbach: You’re currently engaged in a housing analysis study, looking at affordability and hidden living conditions in New York City. Where did that start and where is that going?

Samuels: This is for an exhibition called Uneven Growth that will open later this year at the Museum of Modern Art, and we’re paired with another firm, Cohabitation Strategies in Rotterdam. It was, and in some respects remains, an intimidating scope since housing is a topic that can envelop an entire career.

Visualization of 311 complaints reporting illegal building conversions, 2010-13 | Courtesy of SITU Studio

We decided to focus on one section of the housing crisis, the fact that there is a large hidden population living in dense, shared spaces throughout the city — frequently in illegally converted apartments. This is a population that is, by definition, hard to locate and quantify and thus frequently left out of discussions of housing affordability. This population, mostly recent immigrants, are working in the service sector in the lowest paid jobs and crammed into housing stock that is completely at odds with contemporary use and demographics. For this project, we’re engaging with development and ownership models, since in this case process-driven design doesn’t mean how you fabricate something, but how you actually incentivize and make possible the development of affordable housing in certain neighborhoods that have this hidden density. Of course, we have some ideas about fabrication as well — not as building design, but as a system.

Girit: We’re very interested in modular construction. Although we know all the various benefits, it’s a construction approach that has always faced large hurdles. We’re trying to envision, given the recently completed modular projects in New York City, how it might gain momentum within the right policy environment. We believe modular could be realized as an efficient and lower-cost mode of construction that could also create local manufacturing jobs within neighborhoods where housing is being constructed.

Rozen: In addition, we’re interested in models for distributed agency and participation, meaning how a community can participate in the groundwork for and then realization of a project. This has been a long-standing interest, but now we’re looking at how these ideas might be implemented at a larger, more permanent scale. With some of our temporary structures, such as the solar pavilions, we developed a kit of parts that could be put together freely or organically, and invited people to participate in their construction. With housing, it’s setting up a framework that invites the participation of contractors, manufacturers, and financers. We’re looking at different models for how a community might come together to develop a structure so it’s not always just the five major developers.

Exploring modular housing typologies for the Uneven Growth exhibit | Courtesy of SITU Studio

Samuels: Potentially, all the way through the architectural or spatial decisions. Our early work was about how to take the design problem out of the hands of the architect — or, at least, turning it over a lot earlier as a form of distributed agency. Of course, pavilions and permanent constructions pose completely different challenges. But that is still our ambition.

***

Basar Girit, Aleksey Lukyanov-Cherny, Wes Rozen, and Bradley Samuels, SITU Studio, Emerging Voices 2014, complete lecture video | Recorded March 27, 2014 | Running time: 42:19

***

All four partners met while students at The Cooper Union, where they received their B.Arch. degrees. Rozen has taught at The Cooper Union, Girit at Pratt, and the partners have served as critics and led seminars at a number of institutions. The firm has been awarded an Independent Projects Grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, and a grant from the National Science Foundation. They were winners of the annual Times Square Valentine’s Day Heart Competition, Interior Design Best of Year in the Exhibition/Installation category, and the Award for Excellence in Design from the Art Commission of the City of New York. The Emerging Voices award spotlights individuals and firms based in the United States, Canada, or Mexico with distinct design voices and the potential to influence the disciplines of architecture, landscape design, and urbanism.