Framing Change

Laura Salazar and Pablo Sequero of salazarsequeromedina discuss designing for adaptability, flexibility, and economy across scales.

July 28, 2025

salazarsequeromedina | Entramados Materiales material sourcing process. Image credit: salazarsequeromedina

Laura Salazar, Pablo Sequero, and Juan Medina of salazarsequeromedina are 2025 League Prize winners.

Laura Salazar, Pablo Sequero, and Juan Medina founded design studio salazarsequeromedina in 2020. Often working with repurposed materials, the collaborative practice describes their projects as “open-ended structures” which are realized through dialogue with environmental context and activated by use. In line with this focus on process and adaptability, salazarsequeromedina explored the tension between generic and specific materials in their League Prize installation: a set of ambiguously scaled models located within a series of identical rooms at Pratt University’s MFA Studios.

The League’s program manager Zoe Fruchter spoke with Laura Salazar and Pablo Sequero about the site-specific installation, designing for adaptation, and the large impact of small-scale interventions.

*

Zoe Fruchter: How did you develop your installation concept in relation to this year’s League Prize theme: Plot? Has your relationship with the theme changed since you submitted your portfolio six months ago?

Pablo Sequero: Initially, we were thinking of this idea of entramados materiales, material throughlines, and how every project that we do has a material story that informs it, whether through economy of means or related to site, scarcity, salvaging off cuts, or the re-used materials and off-the-shelf components that we resignify through our design. After we won the League Prize, we thought, let’s explore the idea of material frameworks and material throughlines at the scale of an ambiguous model.

Laura Salazar: The notion of a material throughline or an entramado is about foregrounding process, and how much process informs the outcome of the work. We approached this installation as an opportunity to expose an analog of that process within an entirely different context to the one that we’re accustomed to working in, but using a new set of constraints to go through a similar mode of thinking. In the end, our proposal for the League Prize was about foregrounding an approach.

Sequero: I don’t think [our] definition of plot has changed, but what I see as something valuable and unique [about] the League Prize is that it prompts us to frame our work through a lens that we hadn’t thought through before, and that unpacks different ways of reading our own work, which then informs new work.

Salazar: Yeah, I think the value of the theme is that it destabilizes some of the vocabulary that we have a tendency to use, and this act of reframing opens up new ways to reinsert ongoing concerns under a slightly different umbrella. It’s an opportunity to gain some distance.

salazarsequeromedina | Subway station in Gowanus, Brooklyn juxtaposed against a still from Entramados Materiales. Image credit: salazarsequeromedina

Fruchter: Your work often incorporates repurposed materials. How did you source the materials used in this installation, and what’s next for the pieces now that the show has been taken down?

Salazar: We used a combination of materials that we found in a secondhand warehouse for discarded building materials in Gowanus combined with off-the-shelf hardware store materials. In a way, the whole project was about finding a balance between the generic, standardized quality of the store-bought materials and the highly idiosyncratic repurposed object that has a complexity from a previous use.

Since the installation at the Pratt MFA studios, we’ve deinstalled the pieces but kept them in storage within the building, with the idea that we will set up a second iteration in the fall. We’re interested in iterating the design; what is the final form of these pieces? They’re open-ended explorations that respond to specific qualities of the rooms that they’re built within. We used notions of typological figures—the tower, the plinth, the platform, the line—to help direct their form, but we’re also curious to see how many times you could refigure these things. I think [the new iteration] would be a contextual response, loosely guided by an overall typological direction, that would exhibit a process rather than a static design.

Sequero: I think it’s interesting that the installation was only up for some days, which taps into our interest in transience and semipermanent architecture. In [the installation’s] new iteration, we will probably rehearse a different assembly that transforms or adapts the as-found condition, which is something that we also like to disrupt or adjust.

Fruchter: Entramados Materiales contains formal motifs that can be seen throughout your work: unfinished wood juxtaposed against a metal grid, planes punctuated by holes. Where do these motifs originate from?

salazarsequeromedina, Frank Barkow | The Outdoor Room, Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, Seoul, South Korea, 2023. Image credit: Swan Park

Salazar: We design from an observation of sites and local typologies filter[ed] through abstraction. It’s a process [of mediating] between the generic and the specific [qualities] of a site. Inevitably some figural or formal themes are recurring, but those themes are recurring because we’re interested in a set of ideas relating to the enclosure of an outdoor room. This recurring figure is driven by an interest in generating a sense of belonging and domesticity within the public sphere. There is also always an interest in landing a project deeply within a site, meaning that it really responds to things that are already there. In a way, the tectonic of the project is always interested in grasping its context. Going back to the notion of the wall or perimeter, in some projects we’ve inserted devices by which you could see in and through windows or very specifically located openings. These devices are about directing a view, opening up a new form of intimacy with a public space from the outside, and an invitation to wander in.

Fruchter: As you’ve said, your projects have a strong formal perspective, yet people are what fully activates the work. How do you approach designing programming?

Sequero: Programming is at the roots of each project. The human scale is the anchor point. We strongly believe in this paradigm shift [away] from the monumental sign or sculptoric building. What we’re doing now is on the flip side of that. There’s a lot of practices and architects working now that have reengaged with human scale; the body, how people interact, and different forms of appropriation are really how we start. In terms of use and programming, I think there’s also a general approach of not being super prescriptive, through abstract formal devices or non-prescribed ways of appropriating spaces. This is something that Lacaton & Vassal talk about all the time, this notion of spaces that don’t have a specific use and can be appropriated in different ways.

Salazar: The atmosphere that’s constructed in a project leads to how the space can be used. I keep coming back to our installation Monumental Splash at Concentrico [International Festival of Architecture and Design of Logroño], because it was one of our most successful projects in terms of being completely appropriated, misused, over-populated.

Sequero: Almost to the point where our design doesn’t matter, just because it’s been activated and reinterpreted in so many ways.

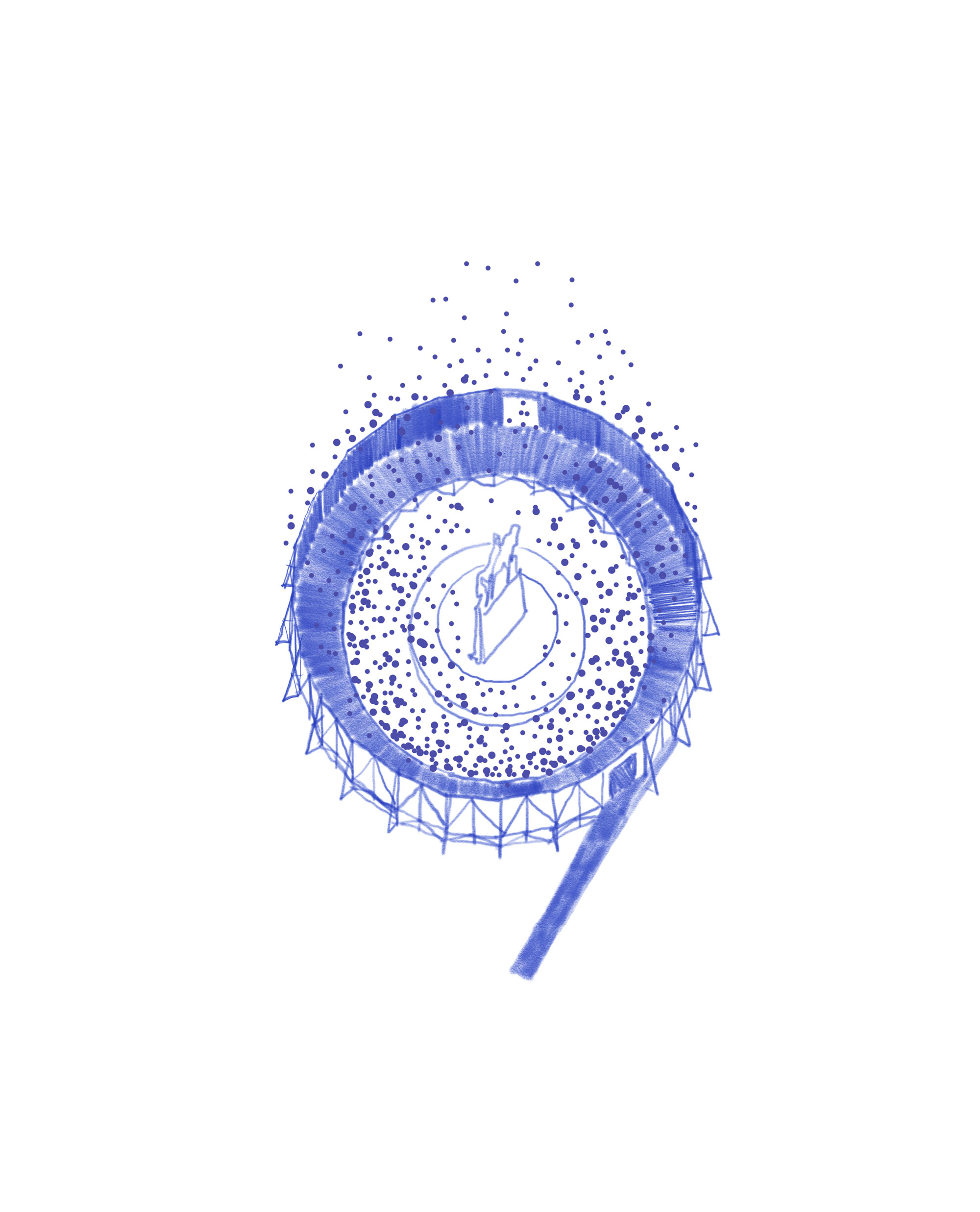

salazarsequeromedina | Monumental Splash sketch, Concentrico International Festival of Architecture and Design of Logroño, Logroño, Spain, 2025. Image credit: salazarsequeromedina

Salazar: There were multiple uses [of that installation] which have become very important lessons for us in terms of how you produce the right atmosphere and access that enables this. [There were] these stylistic devices that I described before, but then it was also essential that we inserted a ramp as the main access to the project. This led to the pavilion being constantly occupied by strollers. A group of disabled children in wheelchairs came through to play with the fountain. And there was a couple that went through on roller skates and another woman that went in with a bicycle as a part of a loop. [The installation] was designed to [have] an accessible ramp, but we didn’t realize the extent of the impact that such a gesture would make in terms of who was allowed in there and how they felt they were allowed to use it.

Fruchter: I’m curious how you understand temporary forms of architecture as a mode of practice, for yourselves and within the field at large.

Sequero: On the one hand, working at the scale of the installation is something that is endemic to our generation, but it’s also the way in which people have always started [their careers], except for this construction bubble that we had in the late 90’s, early 2000’s where every project was huge. But I think precisely because of that shift, we are really comfortable with the impact that very small things allow you to generate. We’re interested in the capacity of installations to have a huge impact: to transform dynamics, rituals, ways in which you understand the city; ways in which you engage with public space, with each other; ways in which you transform even your domestic space, and that’s something that that we think is possible through simple, small-scale interventions.

Salazar: We’re interested in public work, culturally relevant work, and civic space. As a young practice, the way that we have managed to approximate these questions that to us are critical for architecture, is through installations.

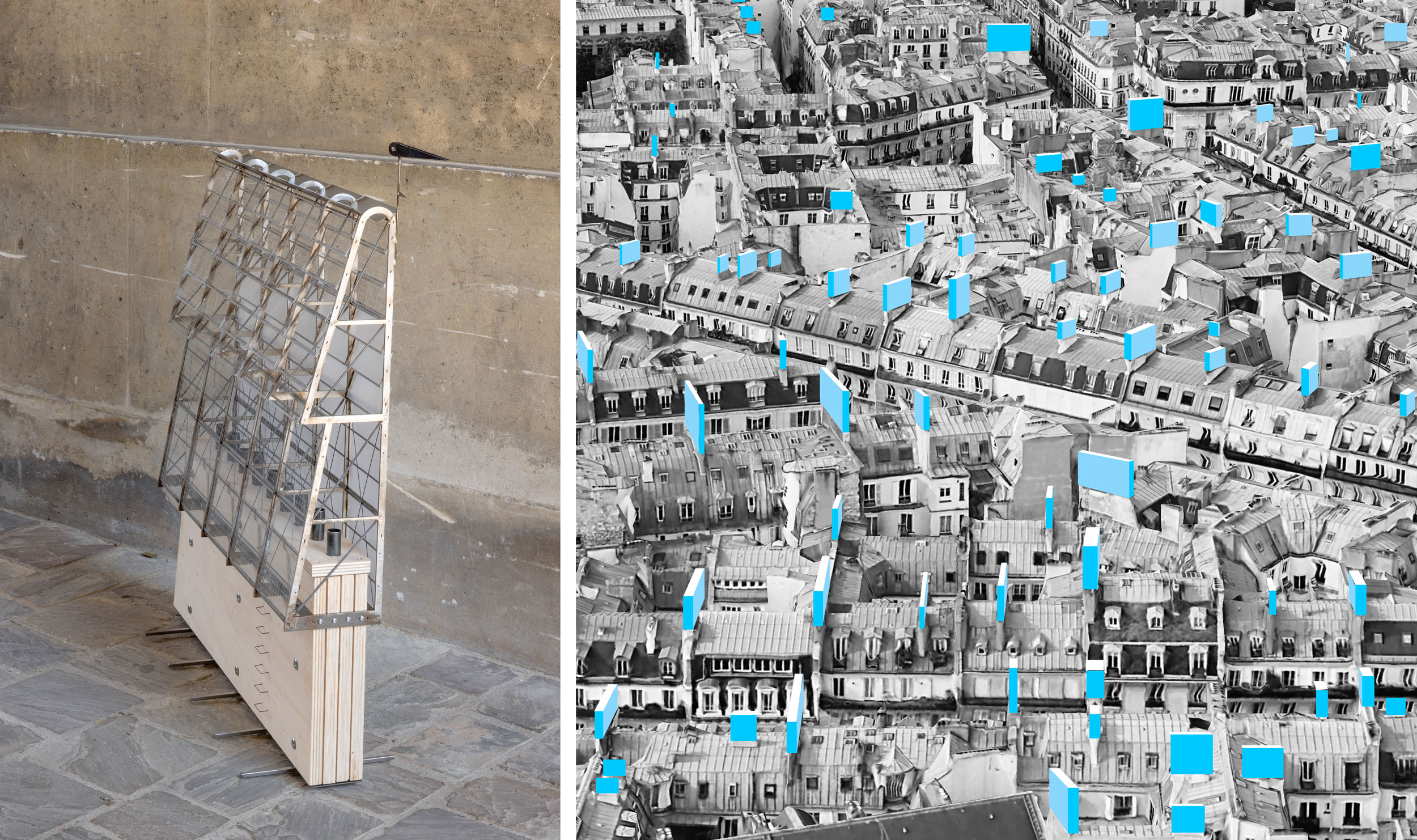

salazarsequeromedina | Murs Solaires, BAP! Île-de-France Architecture and Landscape Biennial, Versailles, France, 2025. Images courtesy salazarsequeromedina

Fruchter: What would it look like to translate these methods to larger scale works in service of your investment in these urgent questions?

Sequero: This relates to the idea that a project can be small—even an object such as a solar chimney, [the focus of] our research project Murs Solaires which we presented at the BAP! Île-de-France Architecture and Landscape Biennial—but have a territorial impact. A project that we always mention is the Palais de Tokyo by Lacaton & Vassal because it brought to the foreground in a radical way that architects have a responsibility to engage and transform what is there and, at the same time, they have the power to produce those changes with very small-scale devices. That’s something we try to pursue with our work.

At the same time, yes, we would also love to work at larger scales. One of the first projects that we did together as a practice was a 45-unit housing building competition in Spain, which we won. That’s when we realized that we had a practice. But that was an interesting project, because scale was thought through in a different way [in our entry], through growth over time, which comes back to the questions of economy of means, adaptation, user agency, etc. So that large-scale project also encapsulated the different scales in which we’re working now.

Salazar: This issue of adaptability and the flexibility of buildings to adapt is critical as a public project. How can structures like the affordable housing project that Pablo mentioned anticipate the future on multiple different scales: from the daily routines of use within the building, to how a family might evolve over time, to the fact that families within contiguous units may not have the same structure, and then to broader questions about the size of building and a greater timescale? Architecture’s ability to provide a stable frame against which these things are allowed to change and become appropriated is really important to us, from a pavilion to a large project.

Interview has been edited and condensed.