On the Table: Dinner with Beth Whittaker, Andrea Soto & Alejandro Guerrero

Two 2015 Emerging Voices were joined by prominent architects, critics, and others in the field to explore the material aesthetic of the handmade and "finding the project within the project"

The League’s annual Emerging Voices program recognizes eight firms with distinct design voices, each invited to lecture throughout the month of March. Following each night of lectures, the evening’s two presenting firms were joined at dinner by prominent architects, critics, and others in the field for informal and lively conversations.

In the following conversation (which has been edited and condensed), Beth Whittaker of Boston-based Merge Architects, Andrea Soto and Alejandro Guerrero of Guadalajara-based ATELIER ARS°, and dinner guests discuss the material aesthetic of the handmade, buildings as machines, and “finding the project within the project.”

Guests gathered following lectures by 2015 Emerging Voices Beth Whittaker of Merge Architects and Andrea Soto and Alejandro Guerrero of ATELIER ARS°

Stella Betts, LEVENBETTS: One of the things that struck me about the two firms this evening is that you both spoke a lot about detailing and materiality. The focus on fabrication and the trend toward architect as maker was, I think, a common denominator between the firms. Beth, I know you did a lot of the fabrication earlier on in your practice. How is that changing now that your projects are growing and it’s obviously more difficult to do those mock-ups?

Three examples of hand-crafted interior walls by Merge Architects | Photos courtesy of the firm

Beth Whittaker, Merge Architects: It’s really hard to scale up that kind of hands-on involvement, admittedly. I’m not even sure that the work necessitates a literal hands-on involvement to achieve the same sensibility for materiality with bigger projects, although I haven’t done enough to know for sure yet. With the Marginal Lofts, the custom stainless steel mesh facade was that project within the project. But that detail was always on the chopping block whenever the budget was tight. It was the last thing to do and the developer didn’t think we needed it — the building looked “fine,” according to the client and the contractor, before we installed it — even though it was always part of the CD set.

Marginal Street Lofts in East Boston by Merge Architects | Photo courtesy of John Horner Photography

The goal is to get everyone to come along with this kind of detailing throughout the design process so that they understand the importance of that moment in the project, whatever it might be: the CNC-cut ribbed wall, the peg wall. Our body of work has that methodology built into it. When clients hire us for a project, we talk about how that’s built into our thinking and they sign up early on for that kind of detailing.

Betts: It was great to hear you talk about not really knowing how you were going to pull off that mesh detail. Alejandro and Andrea, you also spoke about the making that happens on site with the tradespeople and how those kinds of details sometimes just happen during the course of the process. I think that’s really interesting, to kind of let go of the full control of the project.

Alejandro Guerrero, ATELIER ARS°: For the house in Mar Chapálico, with the woven screen facade, we originally designed the house with a different latticework. The project started in 2007 — it’s a house, a seven-year house. In that region, there are these traditional baskets made from the Palo dulce tree, and one day Andrea and I stopped by the road and spoke with this woman who was weaving. We asked the woman to make that work for us, but when she saw the facade she got overwhelmed: “I can’t do that.” A mason at the site suggested we ask fishermen, because fishermen make their own nets. So a fisherman came to the site and made those screens, and at a very, very low cost. Isn’t that incredible? Weaving, or textile architecture, had been in our minds for many years but we never had a project in which we could apply it. This was a natural fit.

ATELIER ARS°’s House in Mar Chapálico, with a hand-woven screen facade | Photo by Onnis Luque

Whittaker: It’s interesting to be trafficking in this kind of material aesthetic — the handmade. Especially now, when architecture is all about digital fabrication. I think it’s interesting to mix the high-tech and the low-tech. My firm is not about high-tech digital fabrication, yet it is a tool that we use as part of our toolbox. We use it to arrive at the stainless steel mesh facade, for example. And it is bizarre that two of our projects actually are in alignment in terms of materiality and fabrication — and incorporate fishnet, in very different materials!

Ken Smith, WORKSHOP: Ken Smith Landscape Architect: I was struck by the idea you presented, Beth, of “finding the project within the project.” I thought that was an interesting notion that applies to both firms. I was struck in both of your work by structural approaches that appear very pure, but are looking for things that work against that structure. Like your sawtooth warehouse, Alejandro and Andrea, that has the end bay with a different proportion. That’s a complicated thing: structurally those bays are completely related, but the design is also opportunistically talking to the street. So how do you find the project within the project? And how does that then hold the whole endeavor together in some way?

The Levering Trade headquarters with sawtooth roof in Zapopan, Mexico by ATELIER ARS° | Photo by Onnis Luque

Alejandro: In our office, we don’t have many projects at one time. But we keep researching and teaching; for example, we are running right now a course about architectural theory and history. If we’re always making projects and projects, we wouldn’t have time to think. But we have time to think. We make drawings about architectural ideas so that when a new project is on our table, we know how to act and we know how to respond because we’ve had time to think about it. For example, the TID Annex is a form about air; its facade with the louvers is an idea we’ve had for a while.

Andrea Soto, ATELIER ARS°: For that project, we went to the board of the department of architecture at ITESO, the university where we teach. We really wanted to do a building on our own campus, but it’s really difficult to build there because you have to be invited into a competition with other architects. So for this project, we went to the board and asked them, “What do you need?” It’s really hard to be trusted as an architect, even if you’re a professor, but a lot of people there already knew our work and said they should give us this opportunity. It’s 200 square meters — it’s really small. We worked on it for maybe a year. We went to all these meetings with a lot of people, and each one of them said, “I need this, I need that.”

TID Annex, a fabrication space for architecture students, at ITESO University by ARS° | Photo by Andrea Soto

Smith: But there are many projects that respond to all those metrics: they solve this, they solve that, and they do all that good stuff. But it doesn’t rise to the poetry of your structural simplicity — that the vent shaft had a proportional relationship to the base was kind of mind-blowing. It goes way beyond the metrics and requirements.

Soto: Yes, and that’s exactly the point. Like Alejandro said, we have a personal agenda — I want to show people how to work with light and air, and how to work through references. Like the hórreos, the primitive granaries. We love this vernacular or primitive architecture, so we try to transform it into a contemporary language. The TID Annex was the perfect moment to try this idea, because the students use the space to apply lacquers and lots of toxic things, so it has to be really ventilated. It’s just common sense — of course you need fresh air, and you don’t need high-tech systems.

The interior of ARS°’s TID Annex, with adjustable walls of wooden louvers | Photo by Onnis Luque

I do want to mention something about the materials, though. We’re used to working with very low budgets. We’ve been in a crisis in our country for the last 50 years and somehow we have gotten used to it. I wouldn’t know what to do if we had a client say, “spend all this money doing whatever you want.” It’s easier to focus when we have to choose materials and be very efficient. We don’t do anything with a decorative purpose because that’s just wasting money. We really like industrial architecture because that is the kind of building you can do with a very low budget. We have found ourselves in that way in the last two years. We believe ourselves to be more like, or we wish to be more like, engineers instead of architects — make it work very efficiently, without making formalized expressions in the architecture. We work our buildings as machines, and we have to focus on the technology we have in our specific epoch, our moment.

Clifford Pearson, Architectural Record: To follow up on Ken’s question, do you tell the client what the project within the project is?

Whittaker: Sometimes. Most of the time. I’m not trying to hide it, because it’s often the most interesting part of the project in terms of the design. A lot of the process is budget driven: you have x amount of dollars to build out 5,000 square feet. You’re not going to put an equal amount of attention and money into the entire project, so it’s about the wall or the furniture or whatever it might be. I think the components where we focus are simple by definition, but actually rich in opportunity for material exploration. The Marginal Lofts was just a dumb box — it’s a smart section, but in a dumb box that’s wrapped in corrugated metal. There was absolutely no luxury spending on anything except for that facade. As with any clients, you have to talk their language, which for developers is about marketability, about something that’s unique versus just a tasteful modern box. Conceptually the core project is often born out of necessity and financial drivers.

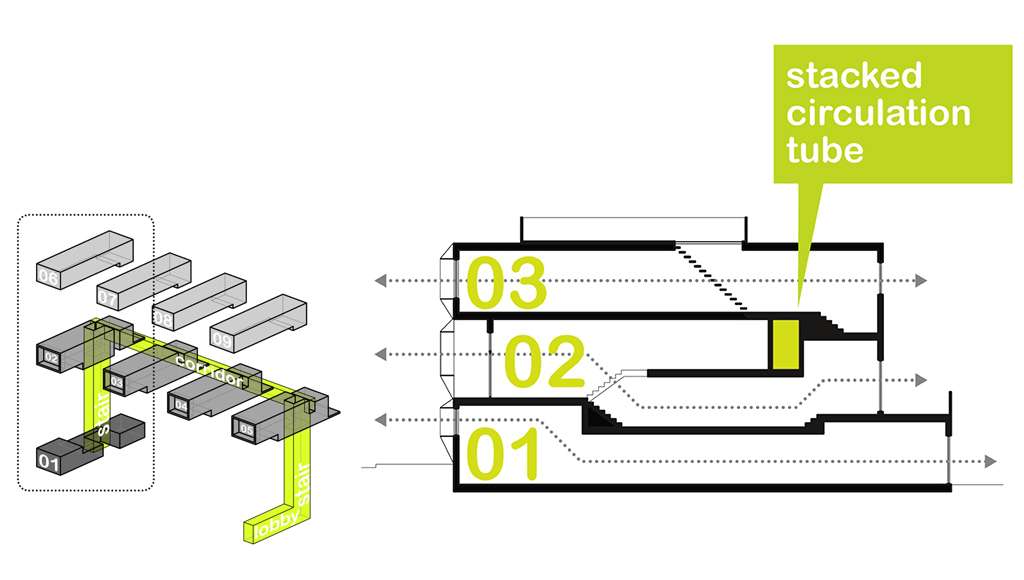

Section diagrams of the nine-unit Marginal Lofts by Merge Architects | Images courtesy of the firm

Mario Gooden, Huff + Gooden Architects: I want to go back to the question of materiality. You both talked about context, but not so much the physical site as the cultural site. For instance, in your discussion of fishermen or woven pieces, you’re sort of dealing with context as a cultural practice. Which I think is what perhaps lends the poetic quality, if you will, to your projects. It resonates at that level — it’s not just the rationality of physical context, but a deeper level of context that a client can relate to.

Whittaker: I think you hit it on the head. There’s a specificity about context with regard to the resources that you can involve and acquire to create a kind of craft. So for us, it was the steel worker that happened to have worked on boats, ironically — he can handle the stainless steel mesh because it’s like fish netting. He had the patience and love, actually, of sewing this facade onto these super-frames. The lattice screen wall made from the Palo dulce tree, Alejandro and Andrea — that’s a very site-specific material that we would never have in Boston. For us, stainless steel is an industrial version of your lattice.

The steel mesh facade of Merge’s Marginal Lofts was hand-sewn by a steel worker who is also a fisherman | Photo courtesy of the firm

The facade of ARS°s House in Mar Chapálico was woven by a fisherman from the area with branches from the Palo dulce tree | Photo courtesy of the firm

Leslie Gill, Leslie Gill Architect: Alejandro and I were talking earlier, and at this moment in time where architecture slips boundaries from one country to another, how do you understand your own work in relationship to work outside of your context? In your and Andrea’s work, I was struck that your projects weren’t really about the individual material, but about the application or how you put those materials together. So I can look at it from my vantage point and both learn and begin to question the assembly in some way. It was easier for me to see that in your work than in the work that comes from America. To me that is one of the most interesting moments — it’s the detail that is both the translator of materiality, but it’s also the point where the materiality shows the cultural heritage in some way. So I don’t think it’s just about an economy — of finding the right labor, or the right application — it’s about understanding how the assembly, construction, and sequencing happen.

David Leven, LEVENBETTS: There’s a fascinating convergence in your work between making and modernism. Modernism and industrialization in the West has gone through a lot of phases of making designed objects rather antiseptic, but there’s this moment right now where the making of modernism is really at the fore. In tropical modernism it’s already been there, so maybe we’re learning now.

Whittaker: I feel a little bit guilty that I don’t directly address modernism in my work because it’s such a given.

Leven: But in your work it’s not just modernism, it’s also industrialization — we have to make boxes for efficiency, so we’re using making as a means to find a project.

Whittaker: They’re almost unconscious assumptions that I admittedly make and I don’t even vocalize, for better or worse, with regard to my background and my education in modernism.

Gooden: But just to play devil’s advocate for a second: the first slides that you showed were of typical types of residential buildings in Boston, and you have made a conscious decision to resist that context or that kind of architecture. Even if you don’t always think about it, there is something embedded which says, “I’m not doing this.”

Whittaker: You know what I think it is? Modernism — if we’re going to use the word modernism, I don’t know that I would’ve — is so embedded in our psyche and education that it’s the baseline for me. A box, a Platonic solid, is a modernist, formal take. The traditional and historical architecture of Boston has very little to do with the kind of form-making and form-thinking that I’ve been doing for the last 20 years. I’m a fish out of water thinking about even beginning to mimic any kind of detailing or formal specificity of the contextual images that I showed. The minimalism and sparseness of a modernist approach feels natural. So for me, it’s step one and then it becomes, I wouldn’t say embellished, but developed for of all the reasons that we’ve been talking about. Maybe that’s a problem, frankly — I should be questioning that.

Rendering of Merge’s Grow Box house in Lexington, MA, now under construction | Image courtesy of the firm

Leven: But maybe it’s not a problem. Maybe it’s, like you’re saying, a basis to start from and also a means to critique both modernism and vernacularism. I just think we’re at a really fascinating moment and I’m wondering, where does this all go? Are we going to go back to antiseptic plastic forms and have backlash against making? It’s a really interesting moment where you can hold up Albert Kahn and you can layer or introduce a sense of making to an industrialized architecture.

Soto: Yes. I think that’s a commonality that we share: we both believe in transformation. Beth, in your opening statement you said, “I’m not going to keep doing this vernacular or romantic architecture. I’m going to change; I’m going to evolve.” In our case, recognizing our references has become a conscious decision and we like to do it. In 2007, Alejandro won the local Biennale in Guadalajara for the SMO House, the one that resembles Mies’ Farnsworth House. And everyone said, “That’s plagiarism.” He had a lot of critics.

Smith: Most people don’t know the difference between copying and critiquing. You should say, “Thank you.”

Soto: Right! “Oh, really? That’s wonderful.” But it was really hard, and I think that was the beginning step for us to construct our manifesto. It’s been a ten-year process.

SMO House by ATELIER ARS° | Photo courtesy of the firm

Guerrero: We became famous by copying the Mies house. I was 30 years old, and it was a kind of weird that a young architect copying a masterpiece won the Biennale.

Whittaker: I think you approached it with such sincerity, exposing that that was exactly what you were doing. There’s something wonderful about admitting that you’re copying intentionally.

Guerrero: Even if I wanted to, I can’t deny it — you look at the house and there’s two slabs, those columns. That house is the work that taught me most of the things I know. With that, we started to think about tradition, but not in a traditional way.

Let me explain something: the houses of our parents in Guadalajara are glass houses. Andrea’s grandmother’s house is a piece of architecture in glass. So that’s exactly the architecture we knew as kids; that is our vernacular. Many of the best works of modern architecture are in Latin America. Brazil, for example, has extraordinary modern architecture in the work of Escola Paulista, among others. So what can I say? Modernism belongs to us.

Alfonso Medina, T38studio: I think every architecture project is about negotiating, and both of your practices have done that really well in really different senses. Developers always have a formula, so, Beth, you’re pushing the envelope to change this level, or exit strategy, or whatever is not about a facade or a detail, it’s really about finding a new model of development. That’s really, really interesting, and not easy to achieve.

In your case, Andrea and Alejandro, I think that you’re a theoretical practice more than a building practice. I find that a lot of theoretical architects don’t like to build because they don’t like to be judged — once you have a building, you can be judged. So it’s very interesting to balance that really theoretical practice with an actual building. What’s it like negotiating with a client, or with an institution, and explaining, “But Mies did this” or “the Parthenon was like this”? Even how you pitch the project must be an interesting process.

Guerrero: We always talk about architecture with our clients. Always. We explain everything to try to make a common language between them and us. If we are building a Mies van der Rohe house, they know about it. No matter who the client is, even a developer. But it’s hard.

Whittaker: It’s very hard. I have to be very careful about how I talk about architecture with certain clients because it can be very alienating. Not only will they not understand, it will scare them into thinking that my ambitions or priorities are not in alignment with theirs. I don’t converse with the intent of deception, but I have to be very careful because the things that are motivating me to sew on a stainless steel mesh facade are not the same reasons that would motivate a developer to pay for it. And frankly, not to sound crass, but when you’re trying to build good work you have to keep your eye on the ball. How do you get it done? So it’s not always about educating them about architecture, although I love that your life allows you to do that! That is amazing.

Medina: But in that sense, it’s about speaking different languages: if you’re talking to a developer you describe the project one way, and then if you’re talking to another architect, it’s a completely different way.

Penn Street Lofts in Quincy, MA by Merge Architects | Photo courtesy of John Horner Photography

Whittaker: I get into the mindset of the client, and I respect the fact that they need to make a buck and that there’s a pro forma that has to perform. So I actually appreciate trying to game code so that they don’t have to pay for that elevator up to the fourth floor. My promise to developers is that we’ll capture a demographic that would have never considered living on that block. And that has been happening with our projects because of the architecture. The Penn Lofts is in Quincy, outside of the city — not as desirable necessarily as Boston to live in, although it has its charm. One of the first buyers was a senior curator for contemporary work at the Museum of Fine Arts. I was elated. You never know who a project is going to resonate with, but you have to provide a spatial experience and amenities to get a curator at the MFA to come live outside of the city next to a Lowe’s store. Because they love it that much.

Elizabeth Whittaker is principal of Boston-based Merge Architects. Andrea Soto and Alejandro Guerrero are principals of Guadalajara-based ATELIER ARS°.