On the Table: Dinner with Alex Anmahian, Nick Winton, Cesar Guerrero & Ana Cecilia Garza

Cesar Guerrero, Ana Cecilia Garza, Alex Anmahian, and Nick Winton joined designers and critics to discuss architects' social responsibilities, building enclosures, and site.

The League’s annual Emerging Voices program recognizes eight firms with distinct design voices, each invited to lecture during the months of March and April. Following each night of lectures, the evening’s two presenting firms were joined at dinner by prominent architects, critics, and others in the field for informal and lively conversation.

In the following conversation (which has been edited and condensed), Cesar Guerrero and Ana Cecilia Garza of S–AR, Alex Anmahian and Nick Winton of Anmahian Winton Architects, and dinner guests discuss an architect’s social responsibilities, building enclosures, and site.

Nader Tehrani, NADAAA: One theme we’ve seen tonight in the work of SA–R and Anmahian Winton Architects has been that of social responsibility. I’m reminded of the way that the media has portrayed this year’s Pritzker Prize winner as having a social program and a political agenda – a portrayal that has dominated the line of reasoning for his selection. But Alejandro Aravena is no innocent lamb – he is a master of form and he understands the challenge of “occasion.” The work presented tonight by both practices is meticulous in its design and also has significant social ambitions, but not all of the work was described in material, technical, and formal terms. How do you reconcile your motivations as a citizen and the agency of the architect as the expert in matters of form, material behavior, and urbanism, such that you bring to the table something that nobody else can?

Cesar Guerrero, S–AR: Well, we don’t see the difference between architecture and social architecture in our own work. For us, architecture should be an activity that we all share. Architecture is an activity that we all share – we, as architects, envision and design buildings, others construct them, and then there are occupants. These aspects make architecture a social activity. We don’t focus on the cost or other technical aspects, instead we focus on an economy of sharing.

Casa Caja by S–AR was constructed by the family that now occupies the house. Photographs © Alejandro Cartagena. Courtesy of the architects.

Henry Cobb, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners: I was very moved by Casa Caja in that the architects and the clients and the builders and the occupants all became one. They were one group, one body working together. This is something almost unimaginable in our stratified American professional culture. What in the end is the relationship between an architect and a client and a builder and an occupant? I think those of us in practice occasionally feel that we are engaged (in some way) with one of those participants. We feel a sense of engagement that we wish could be stronger and more fruitful, if you will. How we, as architects, relate to the constituency that we serve has always been an important question. It’s so refreshing to me to see the practice evolve such that the idea of power and power relationships has been replaced by a sense of equilibrium. Everybody is contributing, and not just in separate ways. Everybody is contributing to the totality of the enterprise.

Guerrero: For us, the difference between one project and another is its size, program, type, materiality, and so forth. But in the end, they are all about building a team of diverse people who are trying to understand common necessities and who are driven to get involved. I don’t know if architects should really separate architecture into all of those categories as a methodology. We have to share to get projects done – when you finish a project, for example, someone moves in or someone uses the building. The construction of architecture is a social process, and the use of architecture is a social project.

Ana Cecilia Garza, S–AR: Most of the architects in Monterrey constantly think about when a client is going to pay for a building. We have to stop looking at architecture that way. Clients who cannot pay us with money find different ways to pay us – maybe by helping to fabricate certain components of the building, like the windows or doors, for example. This helps us complete our work. We are interested in this idea because we see architecture as a shared learning process.

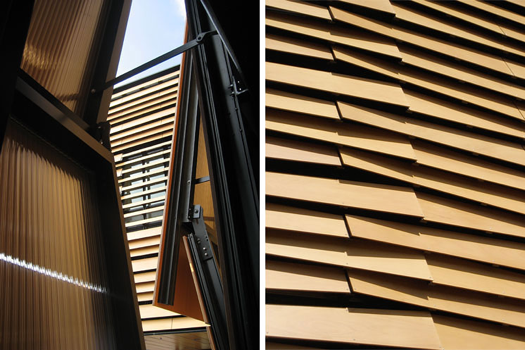

Operable facade of the Community Rowing Boathouse by Anmahian Winton Architects. Photographs courtesy of the architects.

Cobb: Nader’s question touches on a very difficult subject. Anyone who is literate in the history of architecture cannot possibly look at S–AR’s Casa Huastok without thinking about two very significant precedents: the Farnsworth House in Plano (because of its frame) and Schindler’s House in Los Angeles (because of its roof). This brings me to the question of authorship, the meaning of authorship, and the relationship of authorship in architecture to the constituency that we imagine ourselves as serving. I see the Farnsworth House and Schindler House as being part of an idea about a way of life and the relationship of people to the natural world and the constructed world. I would like to hear about those issues from Nick and Alex, in particular about your Community Rowing Boathouse project and its operable facade. I was brought up as a functionalist in the 1940s, so I need to know how things work. And I couldn’t figure out how the facade on the boathouse works, though I admire it enormously.

Paul Lewis, LTL Architects: Yes, I was surprised by the emphasis on skins in both presentations, their articulation and development. Is the issue of architectural expertise best played out in the realm of enclosure? There were a lot of arguments made about the performance of the skin (for Anmahian Winton Architects), the contributions by the blacksmith (for S–AR), and the degree of their operability (for both). You didn’t make arguments about program as much, or even about the flow of people. If you look closely at Nick and Alex’s boathouse, there are many detailed sections through the building. I’m curious if you have anxiety as an architect that your expertise is so focused on issues of image and the performance of the skin. Or is that where our expertise now lies?

Alex Anmahian, Anmahian Winton Architects: We were kind of obsessed with the skin of the boathouse, preoccupied with it even. It was a mistake not to talk about the program though, because it was very much a collaboration between the owner, the client, the users, and us. There wasn’t a frame of reference for the project, because the organization that owns the boathouse had previously used a Quonset hut along the river. Many other boathouses weren’t useful as models either, because our boathouse had to store so many more boats. The building serves an inner city outreach program for girls and boys, veterans, and the Perkins School for the Blind across the street. There was a certain level of discovery throughout the design process for everybody, including the founders of the organization.

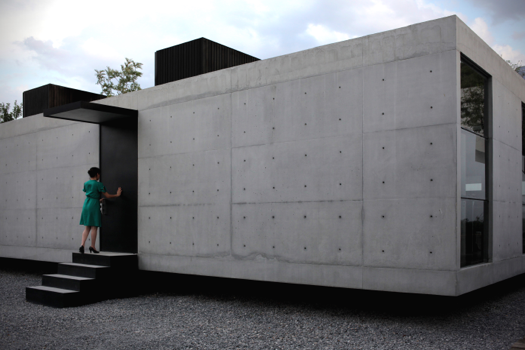

Red Rock House by Anmahian Winton Architects. Photograph © Jane Messinger. Courtesy of the architects.

Joel Sanders, JSA: There is an age-old dilemma in architecture that social responsibility and form are mutually exclusive – I hope it isn’t true! Both S–AR and Anmahian Winton Architects have demonstrated that you can be invested in socially responsible programs and also craft formally engaging buildings that pay exquisite attention to refined details and skins. But in addition to taking on briefs like housing and institutions that benefit the public realm, another way to think about social responsibility is to go one step further and challenge the status quo, positing and envisioning alternative forms of social interaction. Although formally accomplished, S–AR’s houses treat domestic program in a normative way and reproduce standard programmatic adjacencies and conventional domestic relationships. Can domestic design be considered socially responsible if it accepts, rather than challenges, the normative disposition of how people inhabit a house? Is it a restraint?

Guerrero: We think architects should be very practical! People use the spaces we design, so it’s important for us that the function of the space comes easily to the occupant. So our houses are very simple, all of our projects are simple. Our work references modern architectural planning, and part of that is determined by economy. We don’t have projects with big budgets. When we started our practice, we were always thinking of the homemade or other crafts when we designed. And this thinking carries into the drawings. We design details to be affordable, but also easily constructible for builders. It’s a more logical way of designing, but sometimes it’s all that we have to work with for a project.

Garza: Keep in mind, in Mexico, it’s very easy to work with blacksmiths and carpenters. Sometimes, it’s even more expensive to buy a prefabricated window than to work with a craftsman. I’m curious to hear about your own experiences.

A blacksmith crafted the crank (below) used to open a window in Casa 2G (above) by S–AR. Photographs courtesy of the architects.

Nick Winton, Anmahian Winton Architects: This is something I’ve known about the work in Mexico for quite some time. Everything handmade is so much more accessible. Of course, here in the United States, the opposite is true. There is such a high level of production, and the quality of many architectural products drops significantly with a lower price. Craftsmanship is an exception, not the rule. And I think this is in part a result of our culture of mass production. We aren’t engaged with craftsmanship in the same way that we are not engaged with social issues in architecture. There are very few examples of good public housing in the United States, for instance, and no architecture schools teach it. Harry, probably when I was a student at Harvard GSD was the last time that social housing was taught – that was a long time ago! Now, an infatuation with skins and envelopes and enclosures has taken over. We love it because we tinker. But at the same time, I think it has distracted us from other important issues.

Cobb: It’s true that there is an infatuation with envelopes. But if you look at your boathouse, the skin that folds out is not just a matter of skin. It tells you something about the relationship between the people on the outside and the people on the inside and the building and its environment. It’s transformative. It’s not just about the skin. That boathouse is an example of the potential in the building’s envelope to say something about the structure of relationships in the world. And similarly, although you didn’t mention it, Cesar and Ana, I challenge you to deny that Casa Caja was conceived as being part of a very large urban array. Otherwise the solid wall on one side and the garden on the other would be inexplicable. You must have imagined that there would be another house on one side and another house on the other side.

Guerrero: We actually aren’t interested in that.

Cobb: Really? You made the house with privacy on two sides – it implies a very clear division. This is mine and that is yours.

Guerrero: That’s true, we know that. In fact, we receive many e-mails requesting the Casa Caja because it’s cheap and affordable. But the Casa Caja is not a prototype – that would be antithetical to our own philosophy and it would support what we fight against. We believe that all families are different, and so they all deserve different houses. It’s undeniable that Casa Caja could become prototypical, but it was built and designed with one particular family in mind. To us, no one else can use the house as well.

Tehrani: I must ask Ana and Cesar a question about detail. It’s no coincidence that many of your projects are lifted up above the ground and have an inset structure. Those are very deliberate architectural devices that make your houses appear to float – how does that become relevant in the larger conversation that we’re having?

Guerrero: That’s a difficult question.

Tehrani: Because it didn’t happen once – it happened many times. It’s a trope, if you like. It’s an architectural bias. Or maybe it’s part of your authorship, or an indulgence? But it seems like one of those things that we as architects do to ourselves. We betray our sense of geographic specificity and also our sense of material specificity. Maybe we even betray our social agendas. “At all costs, it must float!” But why?

Casa de Madera (above) and Casa Huastok (below) by S–AR both float above the ground. Photographs courtesy of the architects.

Guerrero: Well, we have our reasons. In the first project – Casa 2G – we were accommodating the site’s slight slope. Floating the house kept it level without having to grade the plot. The second project – Casa de Madera – floats because we wanted to keep the house cool. Air comes up through the floor and into the house. The third project – Casa Huastok – floats because we didn’t want to disturb the nature of the site. Animals are free to roam underneath and vegetation was left intact. Those are our reasons.

Sean Anderson, MoMA: In a way, we have seen both offices question the nature of ground, or what the function of the ground is or can be. With Anmahian Winton Architects, inevitably every project, including the office tower in Ankara, frames and reframes the ground as a kind of sanctified space of exchange and of movement. By shifting the experience of the ground in that project, or in the Red Rock House, or in the Ford Hill Observatory, the ground becomes an arbiter of different kinds of experiences and meanings. In S–AR’s projects, it’s a deliberate decision and it obviously has some truth and value to it. Elevating the floor can allow air to cool the building or it can allow animals to pass underneath, but the ground is something that one must transgress as much as a door frame is a threshold. And in Casa Caja, the one project that is not elevated, the ground has a very different meaning – your client spent the last 20 years contributing to that land and is very much a part of it. Whereas Casa Huastok is fundamentally a stage for seeing, removed from the ground. I think in S–AR’s work, the narrative of the ground (or of social responsibility or of the city) is present in many ways. And in Nick and Alex’s work, the narratives are fundamentally about material, structure, function, accommodation, etc. Having seen these projects tonight, what new narratives do you hope to write with your work?

Guerrero: I’m not sure. The scales of our projects are very different. And I think we are more interested in designing small projects, perhaps because there is a greater sense of control for us – we are a pretty small firm. In Mexico, it’s also difficult to find good labor and the right technology to accomplish certain goals. We’ve definitely become established in our community in Monterrey, and we are trying to accomplish some sense of refinement and elegance using the details and architectural devices we have already developed. We don’t have the resources that firms have in this country, but that’s a principle I learned today.

Anmahian: There is a certain nuance in the elevated platforms of your projects. I immediately noticed that S–AR does them in different materials, testing different heights with different ground planes, and I think you may have an interest in the possibility that the same idea or device can negotiate many different situations. It’s a form of design research. I think the answers that you gave are practical ones. But I also think there’s something more that’s of interest, because you adjust them, you play with them in different ways. I found that fascinating. Based on your earlier response to Harry’s question, my guess is that the nuances are based on the individual or the family that you’re designing for.

Winton: And to continue Alex’s thought, I think our goal is to have more agency. Cesar, as you said, architecture is about opportunity and working with people, clients, or communities that really care about architecture – it doesn’t mean that you have to do bigger or more expensive projects. Good design will inherently affect good outcomes, whether they’re social or political or behavioral.

The Capitol Vista Office Tower in Ankara, Turkey (below) and the Ford Hill Observatory (above) by Anmahian Winton Architects. Photographs courtesy of the architects.

Jing Liu, SO–IL: There is an original expression of architecture in both of your practices, but the works also seems deeply rooted in the fabrication technologies and construction skills of the place where you are building. Alex and Nick, I clearly saw your signatures and the techniques you used in many of your projects, from the Berkshires to Turkey. Maybe this is a very personal question to ask, but do you feel that you are obliged to be regionally specific, or do you feel the freedom to explore as a practitioner?

Anmahian: I would say both. I don’t see how I can remove my authorship from the work that I do.

Winton: Or its location. I would love to see S–AR’s work in New England. Cesar and Ana’s designs are so regionally affected in a beautiful way – they are very honest and sincere. Your work is absolutely of your own culture, and your use of material, methods for assembly, and the social order are so clearly of the place. I’m sure you would do very interesting things in a climate and a context that isn’t where you grew up.

Anmahian: Can we ask the question first: Would you work outside of your city if you were asked to?

Guerrero: We have started to work in several places outside of Monterrey. Next year, we will have a project under construction in Central Mexico and another in Baja California. We do believe that there is knowledge in every place, so we are always working with the people who construct our projects. Part of that is trying to bring them something they’ve never experienced before. When the time comes, and we work on a project in another country, the first thing we would do is travel to that country to learn from the culture and site. What are the resources there that we can find to make architecture? What knowledge is embedded in that place? And then, we’ll create with that knowledge. That’s what’s interesting for us.

Garza: Yes, it’s certainly not about taking a concrete block to another country.