On the Table: Dinner with Jon Lott & Heather Roberge

Jon Lott and Heather Roberge joined design professionals and critics to discuss designing homes for writers, and "the denial of a center" in their works

November 30, 2016

Guests gathered following lectures by 2016 Emerging Voices Heather Roberge of Heather Roberge | Murmur, and Jon Lott of PARA Project and Collective-LOK

The League’s annual Emerging Voices program recognizes eight firms with distinct design voices, each invited to lecture throughout the month of March and April. Following each night of lectures, the evening’s two presenting firms were joined at dinner by prominent architects, critics, and others in the field for informal and lively conversations.

In the following conversation (which has been edited and condensed), Heather Roberge of Heather Roberge|Murmur and Jon Lott of PARA Project and Collective-LOK joined dinner guests discuss to discuss designing homes for writers, and “the denial of a center” in their works.

Mario Gooden, Huff + Gooden Architects: Thank you, Jon and Heather, for your excellent lectures. I think that we were struck this evening by some of the similarities between your work. For example, there were what I would call reflexive conditions in the work, such as the butterfly plan or the way in which there were certain Rorschach relationships or mirrored relationships that seemed to occur. I’m thinking of Jon’s renovation of Huntington Hall at Syracuse University with the corner’s reflexive relationship between the environment and interior. And I’m thinking of Heather’s butterfly plan for the house of the screenwriter, which also demarcates a reflexive condition that denies the center.

Heather Roberge, Murmur: While Jon used the term butterfly plan, I described it as a bowtie plan. One of its productive effects is denying a center. Another is its mirror symmetry; one can occupy each half, perceiving the subtle differences between them. In the addition to the Beverly Hills residence, the plan is nearly symmetrical but the section is rotationally symmetrical. One half grows taller toward the private residential yard while the second half rises toward an alley, allowing the experience of the project to be one volume, two halves, and one part duplicated twice.

Jon Lott, PARA Project and Collective-LOK: It’s interesting that you mention denial of the center. This is critical in my work, where there is an awareness of the space that you’re not currently occupying through its relationship to the space that you’re in. I think that the bowtie—and I’ve tried it both in section and plan in several projects—puts the spaces in relationship to each other very acutely. I have an interest in that doubling, that desire created for the space that you’re not in, and I’ve noticed it in Heather’s houses too—a relationship with the other side of the house through a visual connection and tension.

Gooden: I’m also wondering if you might talk about the literal use of reflectivity in your projects. Your work made me think of the Barcelona Pavilion, which one thinks is quite simple in plan. However, the pavilion was meant to be experienced cinematically, with moments where space seems to dissolve and materials dissolve and inner-penetrate. One’s not quite sure what’s inside, or what’s outside. Again that gets to the reflexive condition, a certain kind of complexity that arises out of what appears to be simple. How does complexity arrive out of such forthrightness or directness?

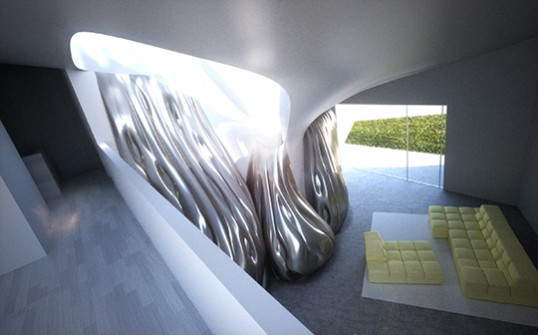

Roberge: I’d like to speak about reflectivity as a transformation or representation of view. The Vortex House is about a continual movement through spaces physically and second experience that cuts across spaces visually; the house produces a kind of endless or excessive experience that overcomes its diminutive size and offers an alternative to the boundlessness of Southern California modernism. Being a Midwesterner living in Los Angeles, I am struck by the way in which hillside landscapes unfold in the city. These landscapes are as much about elevation as ground. They are expansive and also incredibly spatial, much more so than the landscapes of my childhood. And I think my fascination with this difference informs my work spatially. More generally, I think that technology is transforming contemporary visuality through drone photography, Go-Pro cameras, and satellite imagery. The human subject is experiencing a kind of renaissance in vision. These emerging optical instruments are conceptually potent for architects. I’m thinking about how my work might anticipate the forms of perception supported by these new visual fields.

Lott: I gravitate toward reflectivity, both the literal and suggested use of doubling, as a way to dissolve what I would call the objectness of architecture, to confuse the understanding of the object or the boundaries to create awareness among users. The bookcases—in both the Attic and Haffenden House—are a collapsing of beyond and behind, and surface is one way to confuse orientation and boundary to create awareness of oneself in the space.

Gooden: Because we’ve been talking about the construction of subjectivity, or how subjects are constructed, and because both of you have writers as subjects in your spaces—-Heather, you designed a house for a screenwriter, and, Jon, you have two projects for writers—I’m wondering how have your clients responded to the conditions that you’ve created?

Lott: We’ll see in their next book or screenplay, I suppose.

Roberge: My writer pulls down all the shades, so the views produced by the project are denied; he prefers to focus on his laptop. The rest of the family lifts the shades, but the writer insists on working in a visually contained space.

Lott: For the Haffenden House, we fixed the shade, if you will, and created a translucent relationship to the exterior, so that it is light-filled, but not about an outside relationship. The writing studio is very inward focused. And I think that my clients—from what I can tell and from what they tell me—find that helpful.

Fred Bernstein, architecture writer: Hearing you talk about ambiguity and confusion, and seeing the work tonight, I’m wondering if you’ve seen A Japanese Constellation, the architecture show at MoMA? If you haven’t, I imagine you’re familiar with the work of Toyo Ito, Kazuyo Sejima, Ryue Nishizawa, and Sou Fujimoto, among others. Do you consider them influential?

Lott: I definitely feel a connection to many of their projects. The early house by Ito—the White U—and some of that Fujimoto fuzziness are very influential. Sejima’s casualness of the primitive forms that are close to but not perfect and use of ambiguity to get it just outside of familiar—yes, they’re absolutely influential.

Roberge: I’m intrigued by their technical facility. I took students to Japan to look at contemporary projects problematizing the column. We visited Junya Ishigami’s Kanagawa Institute of Technology Workshop, which is incredible both for its spatial ambitions and sleight-of-hand obfuscation of its technical resolution. None of the details of its pinned connections or its technical solutions are revealed. I find the work fascinating conceptually and technically, but the context for building in Los Angeles is really different.

Charles McKinney, Principal Urban Designer, NYC Department of Parks and Recreation: Do you recognize that the way you speak about your work really aligns you with landscape architecture? Oh, and lingerie designers—the way the designs create desire and also thwart it?

Lott: I don’t know any lingerie designers personally. But I do think it’s important to create desire in the work. I think that there are many things that lead to desire. And reflection and doubling and the space that you can’t occupy are really important in this regard.

Roberge: I think my direct references are more to fields like fashion, so I think that your observation is correct. I find an interesting structural problem in skins that are loosely attached to their superstructure. I’m quite interested in the kinds of economies and opportunities that form produces in skins—in things that become lighter and thinner as a result of their shape. And that’s part of the interest in garment making and challenging a kind of tight-fit relationship between buildings, floor plates, superstructure and envelope.

Heather Roberge | Murmur, Proposal for Succulent House, Chicago| Rendering © Heather Roberge | Murmur

Stella Betts, LEVENBETTS: I have two separate questions—–one for each of you. Jon, I’m curious about how you play with light and shadow and the idea of not just being on one side or the other of a space, but also in regards to whether it’s natural light or electric light, and how the scrims that you create in a lot of your work produce a performance of light. Heather, because of the way you were just talking about the relationship of the structure to the skin, I’d like to hear more about the nuts-and-bolts of your fabrication process and the process of making the work itself.

Lott: The question of light—it doesn’t feel like a direct consideration somehow. But when you asked the question, I thought about the need to allure, and managing light can be the variable understanding, even if it’s a vague understanding

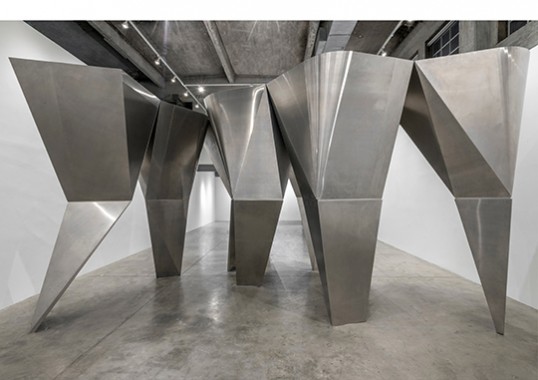

Roberge: It’s very rare that I work on a project for long without thinking about what material I’ll be working with and how I might be able to manipulate that material. This often has to do with wanting to create a correspondence between how a project is produced and the geometric systems that describe it. An example of that is En Pointe, which is maybe the most explicit about its forms of fabrication. All of the forms that were deployed in the project needed to be able to be flattened to a two-dimensional plane, and produced with a specific machine, a press brake. By step or bump braking, which repetitively folds a sheet, you can achieve a faceted approximation of curvature. Single brakes produce a simple faceted surface, while iterative brakes produce curves. The challenge was making sure the column patterns didn’t exceed the limitations of the laser and brakeforming machines I could find and afford. I’ve spent quite a lot of time learning about manufacturing techniques, collecting insights into various forms of production. In studying garment making, for example, I’ve learned how designers overcome the limitations of flat bolts of fabric. This research becomes a resource for resolving future geometric problems. There’s a detail in En Pointe, that was not shown in the slides tonight, where the brake line termination is resolved with a circular cut and a line, allowing a curved fold to end in a point. This solution applies lessons learned from studying garment-making patterns. I’m interested in formal experimentation, and these other forms of production help me resolve the kinds of projects that I want to make.

Steve Hogden, JS Hogden Inc.: There were a lot of similarities between Heather’s En Pointe and Jon’s Heart of Hearts Valentine Pavilion for Times Square.

Roberge: I also thought these projects made an interesting pairing. Jon, how did you fasten it to the ground?

Lott: Weight. There was no fastening to the ground. It was just heavy.

Roberge: Mine were pinned, with two pins, because the columns were subject to torsion due to their silhouettes. By pinning them twice to the ground, the connection resisted the torsion of individual columns.

Betts: They were in a symbiotic relationship, correct?

Roberge: Right. Within this set of nine objects, there were three self-stable sets, allowing us to install without scaffolding and to sequence column erection without concern for intermediate stability during the process.

Lott: The stability with the heart was just a ring, so there was no deviation from symmetry. There is pushing and pulling on itself.

Collective-LOK (Jon Lott, William O’Brien, Jr., and Michael Kubo) | Heart of Hearts installation | New York City | Photo © David Sundberg, Esto

Andy Bernheimer, Bernheimer Architecture: One of the great things about tonight is a reminder that we’re inspired by things outside our field. But what happens maybe after that moment of inspiration? What is the first move?

Lott: There is a kind of hunch—most often based on current preoccupations, as you say, outside the discipline—that you get from analyzing the context, program, and desires of the client that I both try to put in both check and chase. Most often this check and chase is a productive second guess of these other/outside streams and their potential influence on the work. Of course, there is a relationship to what has been experimented with before, in previous projects, so the first move is a synthetic processing of requirements with previous agendas that align with the kind of move at hand. That’s not a very direct answer. The direct answer is to chase the hunch based on current curiosities. It’s this ecstasy of influence that informs the first move.

Roberge: I am fundamentally rather pragmatic, so I prefer to parallel process material and conceptual issues. I’ll figure out what my architectural inquiry is—conceptually, what do I want to think about right now, what are my material, schedule and budget constraints, what are my site conditions? I really love drawing, especially plans, so I typically start by planning a project in relation to site, circulation, and program, and then I develop it three dimensionally. I always have an understanding of sequence and space before I really get involved in synthesizing the various project constraints I’ve identified.