Design as anthropological experiment

The founders of New Affiliates want to rewire how their clients think about architecture.

New Affiliates is a 2020 League Prize winner.

New York City-based New Affiliates was founded by Ivi Diamantopoulou and Jaffer Kolb in 2016. The Architectural League’s program director, Anne Rieselbach, spoke with the partners about their work.

*

Anne Rieselbach: In your League Prize submission, you wrote about how the field of economic anthropology has influenced your thinking about material reuse and adaptation. Can you say more about this idea?

Jaffer Kolb: Economic anthropology is a subset of economics that developed in the mid 20th century as a response to the idea that markets don’t always operate with total efficiency. The thinking was, if efficiency doesn’t govern our decisions, what does? The answer usually has to do with society or culture or desire or human behavior.

What appeals to us about this is the thought that, since things like culture and behavior are flexible, maybe we could use them as ways to rewire the way that our clients desire things. Architecture is a profession that responds to the demands of the market: we get paid, we have clients. It’s a service industry. And we love that it’s a service industry. But could service itself have some flexibility built into it? Could we come up with new ways of influencing the way that clients think and operate in order to create new kinds of architecture?

Ivi Diamantopoulou: We started our office with a shared desire to dive into practice. Like most young offices, we would say yes to everything: no project’s too small, no work not interesting. Seeing projects, small or large, from design through construction is exciting; there are so many moving parts!

We’ve always treated the process itself a bit like an anthropological experiment, keeping a close eye on the actors and logistics behind architectural production: what is available to us, where it comes from, how long it will be there, who is involved and how. Our interest in tracking material lives and thinking of new kinds of scales of reuse is a direct result of these kinds of observations, which have begun to take on a life of their own as new projects.

Rieselbach: How did your collaboration with the New York City Department of Sanitation come about? What have you learned through this work?

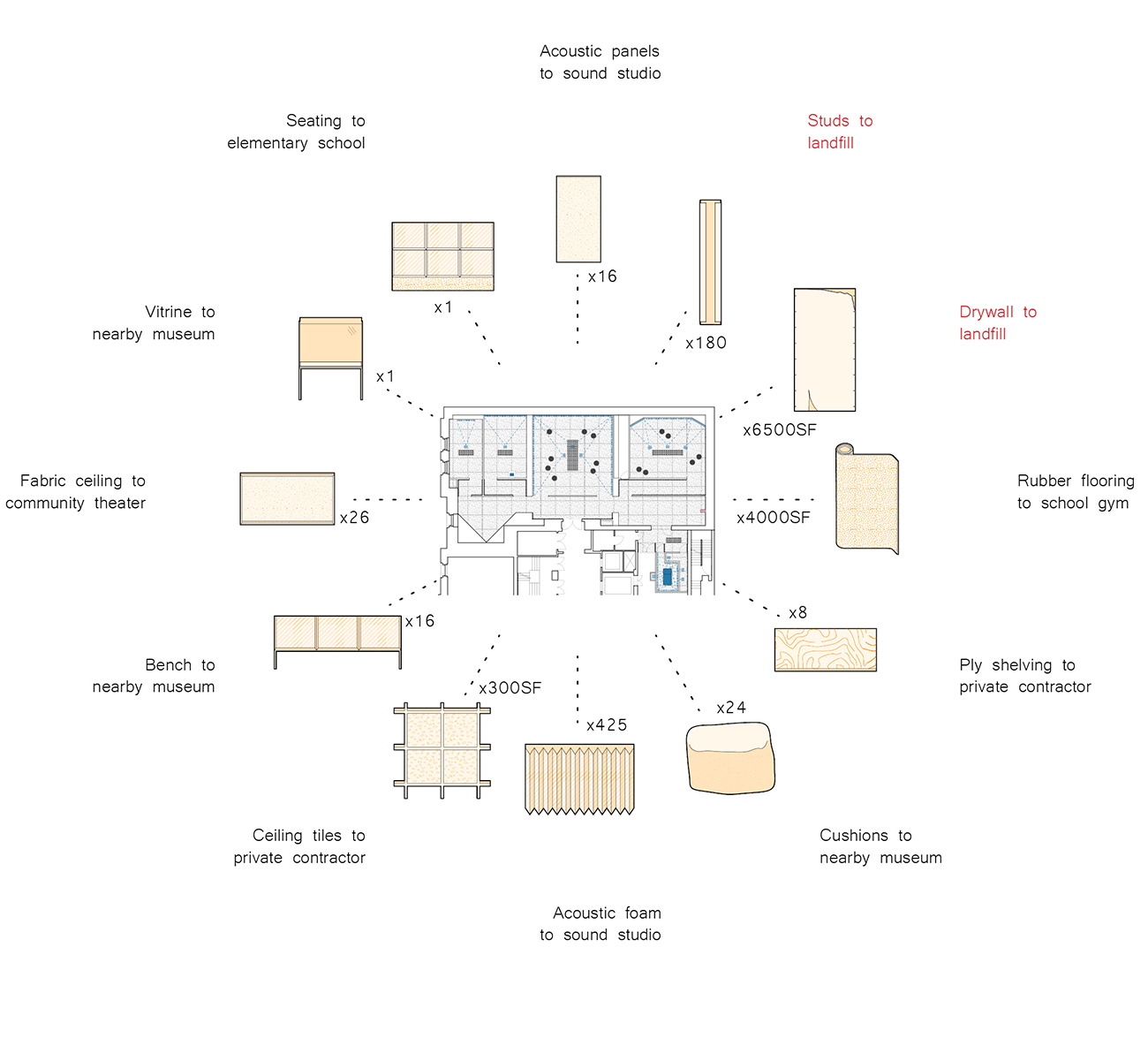

Diamantopoulou: We do a lot of exhibition design, which, as you can imagine, usually leads to a sad story—the exhibition goes up, we celebrate, and then a few months later it all gets torn down and thrown in the garbage.

We decided to design the Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything show at the Jewish Museum so that it could be disassembled when it was over. The show was essentially 12 artists responding to the work of Leonard Cohen, so it wasn’t so much about presenting paraphernalia from his career, but rather producing conceptual pieces. The main design challenge was, how do you take a 19th-century mansion and turn it into a collection of acoustically isolated microenvironments?

Within the very specific scope of this project, we aspired to catalog all the materials we were using and specify them so that they would be removable after the show. We contacted the Department of Sanitation early on in the process and worked alongside their team and the museum to look for places to send the materials when they were taken down.

Kolb: We’re both big fans of Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who’s been the artist in residence at the Department of Sanitation since the ’70s. That’s partially why we had this desire to do something with them—we were looking for some excuse to get in touch.

Issues like obsolescence or expendability or newness come up a lot in our work. Working as a small office in New York leads you to think through time cycles in a weird way. The city is kind of a machine of constant motion, and part of that constant motion is making and remaking things over and over. Our desire to contact the Department of Sanitation came partly out of our interest in Ukeles, but also partly from trying to understand how, as designers, we can intervene in that cycle of constant regeneration.

Rieselbach: How did this concept influence your Drywall is Forever piece?

Kolb: It very much came out of that. Right around the time the Leonard Cohen show was coming down, we were contacted out of the blue by Performa, saying “We’d like you guys to do a performance for us.” This was not like anything we’ve ever done before; I think we were both a little freaked out by it. What does performance mean? Do we do choreography now? Do we become actors?

Then we thought, well, why don’t we tap into the work we’re already doing with the Department of Sanitation—because actually, architecture is a different scale of performance, right? The erection of buildings and dismantling thereof; where the raw materials come from and where the waste goes. If you were to zoom out over space and time, you’d see that this whole network of exchanges is like a really beautiful orchestrated performance.

One thing we learned from the Leonard Cohen show is that it was possible to give away 90% of the stuff we used, but not the walls. So we thought, let’s take on drywall and see what we can do with it.

Diamantopoulou: If you think about it, drywall is the largest common denominator, materially speaking, in museum galleries. And it’s the one thing you can count on finding in any given museum dumpster during de-install, no matter what the show looked like. It’s too cheap to think twice before discarding, tricky to recycle, and ultimately truly problematic from an environmental standpoint.

We collected all these leftover pieces from museums that were taking shows down at the time, and imagined we could stitch them together into a new gallery wall—one that is scarred, or ornate, depending on how you read it. We looked back at Brian O’Doherty’s writings on the white cube and his critique of displaying art in anonymous, timeless, apolitical space. And we also looked at our own discipline and our fascination with all things seamless and polished.

Imperfection and inefficiency come up a lot in our reuse work. As we’re working with found parts, whether materials, objects, or assemblies, standards fail us, and so do typical details. For this one wall, for example, we had to rethink the distance between studs, come up with a strategy for arranging pieces of varying thickness, find a mix of compounds for massive joints between their irregular edges.

We’re used to copying the same partition detail from one drawing set to the next and don’t even think about these things anymore. But typical details are the result of material standardization, and working with one-off fragments becomes generative.

Rieselbach: Shifting scale, what was the inspiration for your Garden Test-beds project?

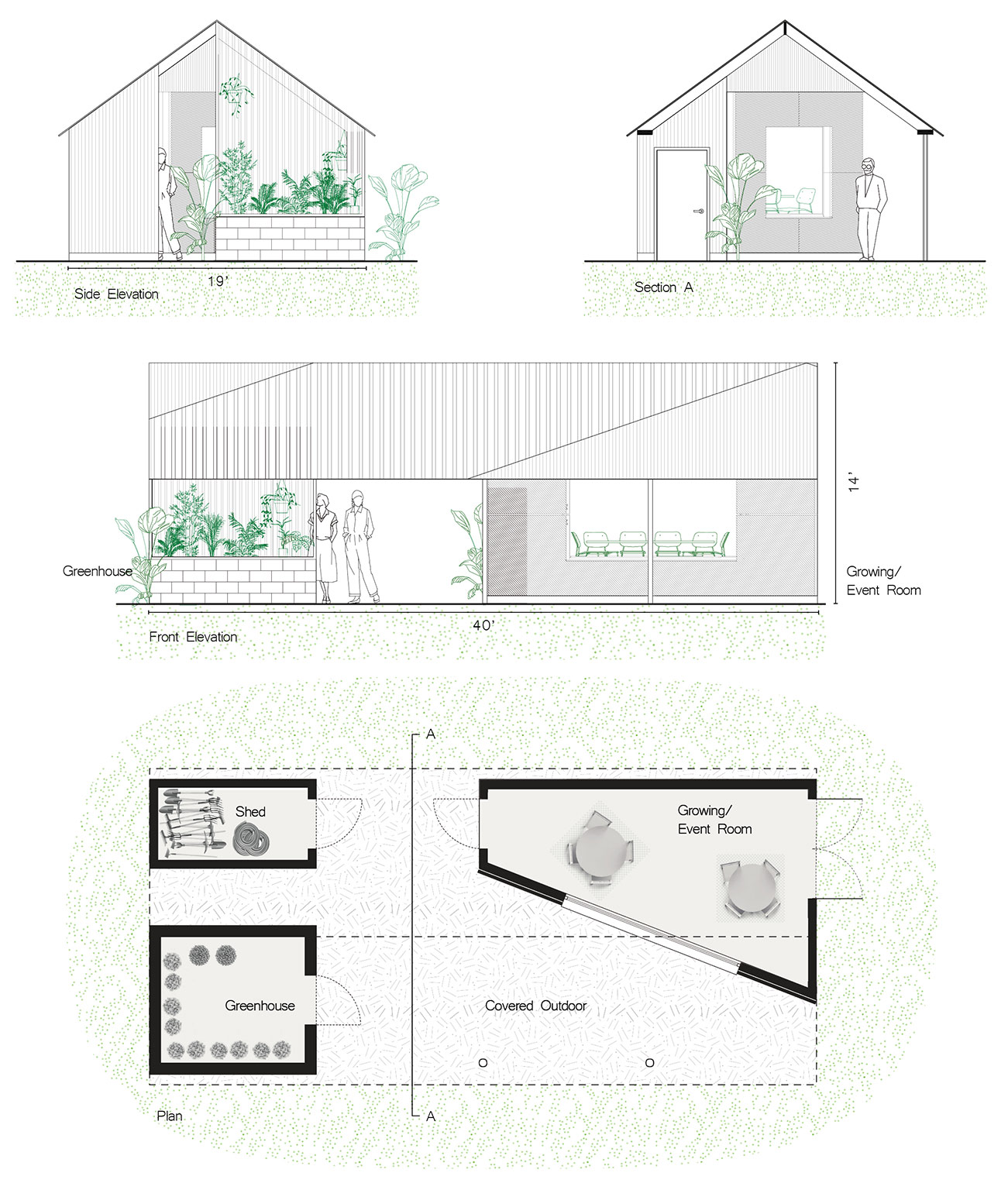

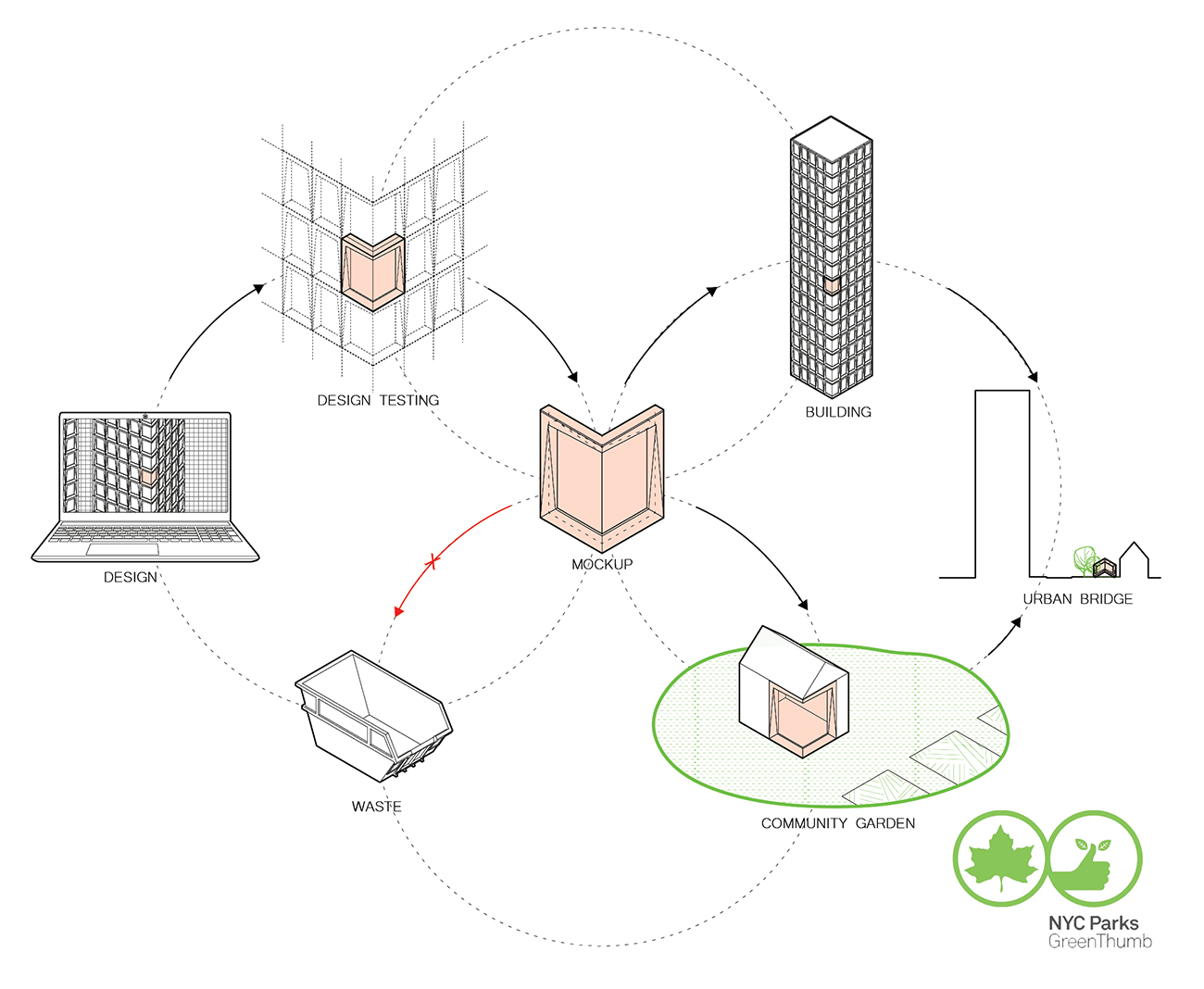

Kolb: Our Department of Sanitation relationship came out of frustration over wasted materials. This one came out of a consideration about how the architecture profession operates. We did the project in collaboration with a good friend who is a historian at Columbia, Samuel Stewart-Halevy. We were thinking about ways that architects create byproducts through testing. Every time a fancy new building gets built, they make one of these mockups, which go for $100,000–$300,000, if not more. They build them out of the real materials of the building—stone, aluminum, steel, marble, glass.

So we started investigating if, in fact, these really get thrown away after they’re used for review—and it turns out that they do. We went to a testing facility called Intertek out in Pennsylvania. We started the project through six months of interviews with architects, contractors, developers, and engineers, to try and get a sense of what was happening with these mockups and to see if we could find something to do with them.

Then it was really just through walking around the city that we were like, “Oh, there’s like a funny resonance with little garden structures. What if we use them as cornerstones or anchor pieces for a casita or a greenhouse?”

Rieselbach: Were you thinking about it in a larger, systemic way? Do you think it would be possible to develop a system for identifying mockups and other potentially reusable building elements, as well as potential sites for reinvention?

Diamantopoulou: Absolutely. For us, it’s always been about inventing a system that turns the waste stream into a resource. We’re up to year two on the project. It’s been a steep learning curve in terms of understanding all the stakeholders and voices at the table. Our idea has been to make one project work, learn through that experience, then do more. The numbers of mockups produced and then thrown away is extraordinary. These are resources that we could be capitalizing on. So yes, we are actively thinking of starting a rescue foundation, so to speak.

It’s been very interesting to work with communities for this project too. Most gardens are run by small groups of individuals of varying ages and skill sets and interests. You arrive with a strange idea. Each time we ask, “Hey, there’s this thing, do you want it? What do you want to do with it? Can we design this together?” There are a lot of twists and turns. We’ll have a long meeting with a garden group, and then at the next meeting someone who missed the other meeting will turn everything on its head. It’s a long process.

Meanwhile, mockups typically get discarded immediately after being reviewed and approved; testing facility real estate is steep. Getting the two to align takes a bit of luck. But we are optimistic that once one is completed, we will know how to navigate both conversations with more precision.

Rieselbach: How has this approach to reevaluation and reuse influenced other projects that you’re working on?

Kolb: For us, all our work is very much a project of design, not simply, “We look at how to rearrange material flows.” We’re always trying to understand how architectural design represents this assemblage of different components. Somewhat classically, we see our work as being coordinators and orchestrators of materials and of contractors and subconsultants. We try to enter into every project as though it’s a novel network of things that are both immaterial and material. So from expertise through to literal pieces of materials, site, etc., that’s inflected how we design in both directions.

Simply put, I think we came to the project of reuse as designers, and I think we’ve learned from it as designers.

One of the things that was interesting about the Department of Sanitation collaboration is that at a certain point, we had to have this conversation with them about, like, “We’re not going to start a reuse center here. Our interest isn’t making a database so that everyone can list things and then borrow them.” There’s a ton of value in both of those things, but that’s not where our expertise lies, and it’s frankly not what engages us as designers.

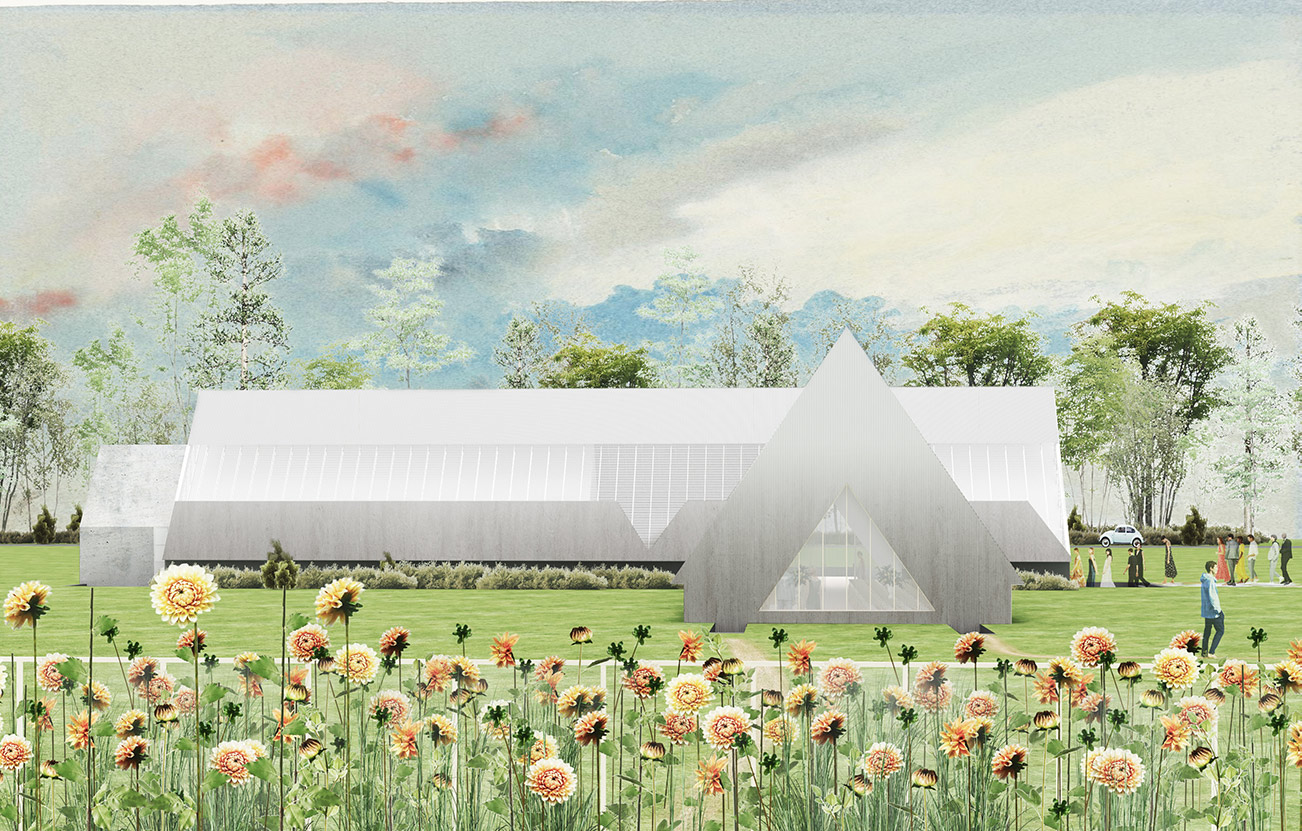

But we try to bring the logics of material ecology and material economies into every project, even ground-up projects. I think specifically about the Michigan farmstead, which was designed a few years after we were doing a lot of the reuse work and thinking through these issues. We were really excited, of course, about the opportunity to do a ground-up, which, when you’re a New York-based architect, are few and far between. But instead of just saying, “Well, it’s a ground-up, so let’s think from the ground up,” our first thought was, “Okay, we want to rely on a network of materials and experts that are out there building things for farms in a kind of industrial apparatus.”

That’s why we were immediately drawn to steel-frame building types. Architects are forever bemoaning parts of our profession that are lost to standardization. You can just go online and order a custom barn made out of steel structure and never talk to an architect. You put the order in, the building arrives on site, and it gets built out.

We thought, instead of feeling upset about that, why don’t we start by pretending we’re a client ordering a steel barn? Then, as designers, let’s enter into that, figure out new ways to make a new program out of it, figure out ways to supplement, augment, transform, or use that as a starting point to do something totally different and unexpected. That felt like a really exciting way to take on the project while confronting a kind of Achilles’ heel in the profession.

That was a logical extension of our conversations around the Department of Sanitation, the Test-beds project, and reuse—asking how we give ourselves constraints that are like fragments of architectural forms that we can respond to and build from. That increasingly that’s a way we think and work.

Diamantopoulou: No project starts with an empty piece of paper anymore. There’s just no way. This is not where the world is.

Interview conducted on May 22, 2020.

Edited and condensed.

Explore

Everything old is new again

For Miriam Peterson and Nathan Rich, adaptive reuse projects offer uniquely exciting design challenges.

Material flows, ecosystem growth, and urban landscape renewal

Paul Mankiewicz explores ways to improve the environmental, infrastructural, and economic health of cities.

Annabelle Selldorf lecture

A lecture by Annabelle Selldorf, who works nimbly within a wide range of architectural typologies.