Brick Construction from Córdoba to Cambridge

Juan Manuel Balsa, Rocio Crosetto Brizzio, and Leandro Piazzi of BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI discuss their historically engaged installation at MIT and compare architectural practice in the U.S. and Argentina.

August 11, 2025

BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI, GIORGIS ORTIZ | 12 Rooms installation process, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2025. Image credit: BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI & GIORGIS ORTIZ

Juan Manuel Balsa, Rocio Crosetto Brizzio, and Leandro Piazzi of BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI are 2025 League Prize winners.

Founded in 2014, BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI is an architecture firm based in the United States and Argentina led by Juan Manuel Balsa, Rocio Crosetto Brizzio, and Leandro Piazzi. Rooted in attention to materiality and building methods, the firm’s projects range from ground-up residential work to public installations. One such project is 12 Rooms, a temporary work that the firm, with GIORGIS ORTIZ, installed at MIT’s Kresge Oval which reconstructs the spaces at the Institute where pivotal inventions and research were born. For their League Prize installation, BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI produced a video reflecting on brick construction in Cambridge in relation to the installation alongside documentation of the construction process.

League Programs and Membership Assistant Demasi Darby-Washington spoke with the three partners about the methods and values which underlie the 12 Rooms installation, and how the firm has built a practice between two countries.

*

Demasi Darby-Washington: In your own words, 12 Rooms sits between documenting the past and constructing the traces of a new possible space. How does the installation bridge the site’s history with the possibilities that it aims to create?

BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI, GIORGIS ORTIZ | 12 Rooms team adjusting the final details of the installation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2025. Image credit: BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI & GIORGIS ORTIZ

Rocio Crosetto Brizzio: This project had a very strong research component. We looked into these buildings, some of which belonged to MIT’s original Boston campus but were demolished, and others which are part of the current campus but have been altered. The first question was how to select the rooms and history to include, which was a long process, because we were aiming to frame inventions and breakthroughs from many departments.

Juan Manuel Balsa: The project works with the typological idea of the room—a fundamental and recurring space in architectural history. Through traces of memory, each room evokes a space where important ideas at MIT were born, now reconfigured as a new form of collective public space.

Leandro Piazzi: The rooms [we selected] were labs, classrooms, offices, lecture halls which are most times secluded and not accessible to everyone. By bringing a scaled version of these rooms to the Kresge Oval we aim to connect MIT’s history with the broader community of Cambridge.

Crosetto Brizzio: To place these historical spaces from somewhat unknown buildings outdoors is like tracing a new possible space,and allowing for people to occupy [that space] in different ways. It is like marking a thicker line on the ground; to produce a project that will make room for things to happen.

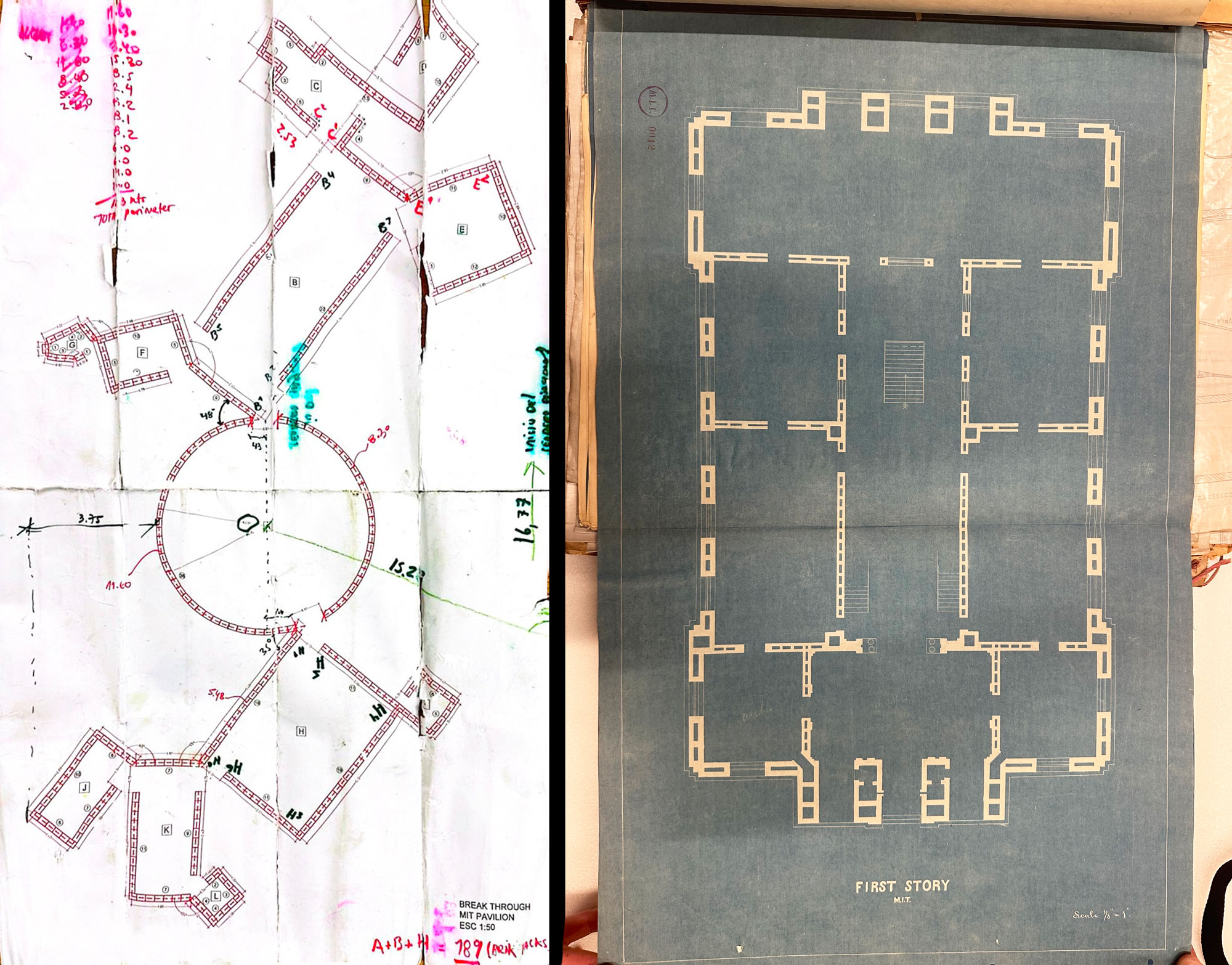

BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI | 12 Rooms printed plan used to mark the ground, damaged by some rain, and the Rogers Building first floor plan blueprint from the MIT Museum Historical Collections, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2025. Image credit: BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI

Darby-Washington: During your lecture, you spoke about viewing the United States as a place for architectural experimentation. As a firm based in the United States and Argentina, can you expand on that idea and share how 12 Rooms embodies that perspective?

Balsa: Our practice is [based] in the interior of Argentina, not Buenos Aires, and that’s very important. A rural and peripheral context demands simple, efficient, and local solutions. 12 Rooms was an opportunity to apply the same logic—common materials, simple techniques, proposing an accessible and collective space—to an urban, academic context.

Piazzi: We enjoy the differences between Argentina and the United States in the way that we approach our practice, research, and work. We go back and forth between the two worlds and they feed each other. Argentina gives us the opportunity to build in a, let’s say, more canonical way. We have been working there for 10 years now and we have a network of people who ask us to design buildings, from rural infrastructure to residential buildings. There’s a huge need for housing, and a lot of opportunities for a young practice.

Shifting to the U.S., the three of us teach at different universities. In the U.S. we are expected to have a deeper research approach. And we are supported by the institutions where we work to create a scale of architecture that engages with the public, with different technologies, and with the idea of temporality. That kind of architecture is not common in South America: to make a pavilion that costs money and then disappears is very hard to do in an environment with economic scarcity.

BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI, GIORGIS ORTIZ | MIT graduate students David and Jonathan during 12 Rooms project installation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2025. Image credit: BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI & GIORGIS ORTIZ

Crosetto Brizzio: Projects like 12 Rooms allow us to test things. Most projects in Argentina respond to very specific commissions and precise questions. Of course, you can experiment there, but it takes longer, whereas in the U.S. [there are] grants and opportunities to be part of an exhibition with other people discussing the same subject which allow you to develop your thinking and gain tools for larger projects. For example, in 12 Rooms we developed a dry stack assembly of bricks that we call “the brick pack,” which relates to our interest in democratizing the building process through different assemblies of low tech materials.

Darby-Washington: How did the materiality of brick inform the Plot or composition of the installation?

Crosetto Brizzio: We feel very identified with brick, because we are from Córdoba, which has a huge culture of building with bricks. Many of our most renowned architects and people who have been our professors build with bricks. We discovered that brick was also part of the history and the culture of Cambridge—of course, you have the references of the Alvar Aalto Baker House and Saarinen buildings close by. The materiality came from being aware of our context and wanting to work with it.

Piazzi: The brick material implies history and has carbon and energy implications, but it’s important how you put the bricks together. In 12 Rooms, we packed the brick so that we can disassemble and repurpose it. We’ve been experimenting with how to reduce the energy footprint of temporary architecture. We believe that this is crucial. Our pavilions, both in terms of materiality and technique, are always part of a larger cycle of life. This can be seen in other projects of our office such as the IX BIAU Pavilion in Rosario, Argentina or Bethel Woods Pavilion in Woodstock, NY.

Balsa: I was thinking about the relationship between temporality and architecture, specifically with the bricks. For our projects in Argentina, the bonding material between the bricks is concrete. In 12 Rooms, the bond is a strap. The [meaning of the] brick is associated not with the material but with its bond: If you join two bricks with mortar, it’s permanent, but if you join the bricks with a strap, the logic changes and you can later transform this architecture.

Darby-Washington: The way 12 Rooms reconstructs and highlights traces of the past evokes a powerful sense of memory, much like a memorial or monument. Did you approach the design with these typologies in mind?

BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI, GIORGIS ORTIZ | MIT inventions plaque within 12 Rooms, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2025. Image credit: BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI & GIORGIS ORTIZ

Crosetto Brizzio: We haven’t thought about that directly, but I understand the connection. The pavilion was part of Artfinity [an Institute-sponsored event celebrating creativity and community at MIT]. A celebration is the same thing [as a memorial] but with a different atmospheric ethos of the memory. Each room had a plaque identifying the room number and the specific invention that took place in that room and the people who were part of that. The plaques brought people into the installation and started conversations. It was an important detail within the more abstract space.

Balsa: We always try to create a strong connection with the past in our projects. In Argentina, many projects are opportunities to engage with certain historic typologies. For example, our 3 Patios House emerged from the plan of the oldest house in Córdoba, La Casa del Marqués de Sobremonte, a 16th century courtyard home, or our Long House comes from a continuous obsession with the Casa Chorizo, the typical immigrant house that has populated Argentina in the late nineteenth century

Piazzi: We’re interested in working within an existing legacy of techniques and materials. Invention is not our main goal; we’re trying to build good buildings for people to live in. In Argentina, it’s a social thing: we have amazing masons and working with masonry supports this community of laborers, their families, and the economics of construction in the places where we work. This connects back to choosing [to work with] bricks in Cambridge. That is our way to establish a dialogue with the past, present, and future—but it’s a dialog that already exists. The project takes part of a longer existing conversation and tries to add something to it. We could say that this is our general and consistent position in architecture.

Darby-Washington: 12 Rooms comprises various mediums: a built installation, video, photographs, and drawings. How do these different modes of representation work together to create a cohesive and layered experience for the viewer?

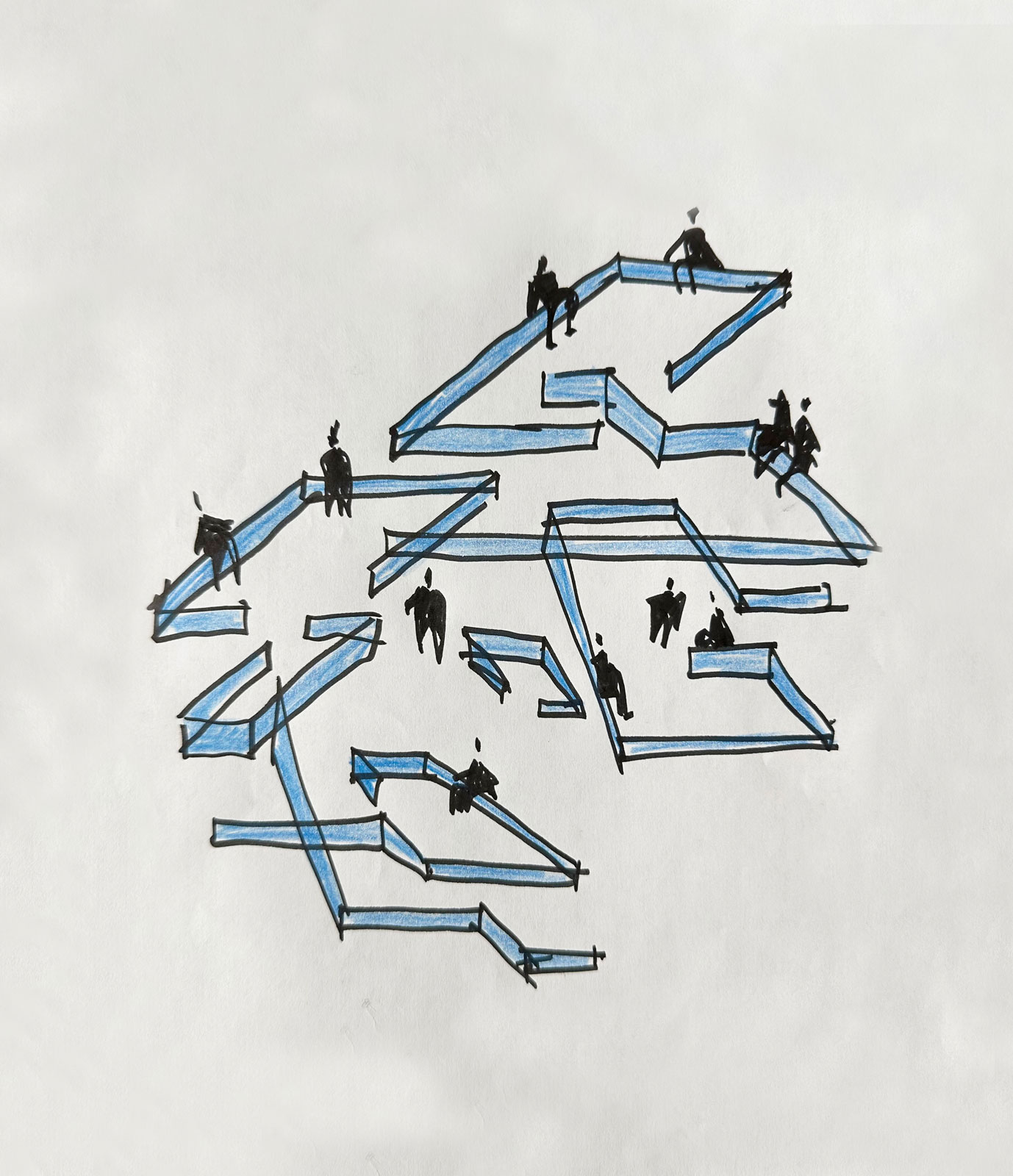

BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI | 12 Rooms initial conceptual sketch, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2025. Image credit: BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI

Crosetto Brizzio: The built project is our primary medium. It constitutes the reason why we are architects. But it is true that each form of media shows different aspects of the project and, very importantly, allows us to look at the project again in multiple and alternative ways. The drawings are quite abstract, focusing more on the compositional and geometrical dimension of the project. The video picks up on the contextual condition: the bricks in the built environment of Cambridge and seeing the installation in place. And the photographs capture special moments of visitors occupying the space.

Piazzi: One of the most exciting parts of the League Prize exhibition process was the opportunity to “unfold” this building through different mediums. For instance, the isometric becomes a very important part of the drawings because everything looks very flat in the photos.

Even if the height of the brick walls was 30 centimeters, the isometric drawing allows us to explain its three dimensionality. This post-production moment was important for us to rethink what we did, how we did it, and how we can engage a larger audience. It’s the absolute inverse of when you build something and you produce all the documentation first; it is a retrospective way of looking and drawing

Darby-Washington: What is the next chapter for the 12 Rooms project and its underlying concepts?

Crosetto Brizzio: We are working on a pavilion for the Chicago Architectural Biennial right now which connects to 12 Rooms but responds to a different set of challenges. The project operates within a similar construction logic using other types of bricks, connected to Chicago’s own history of brick construction. Similarly, bricks and this construction logic has relevance throughout our practice, including projects we are working on in Argentina.

BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI, GIORGIS ORTIZ | Adriana and Farnaz pulling the cart with the remaining broken bricks after the installation, with the Saarinen Chapel wall in the background, MIT, Cambridge, MA, 2025. Image credit: BALSA CROSETTO PIAZZI & GIORGIS ORTIZ

Piazzi: What is next is to keep the same attitude—the attitude of doing things, building things, working with local communities and resources in an economical and simple manner, bridging the gap between academia and practice.

Crosetto Brizzio: Next is to keep going; to keep teaching and doing architecture projects. It’s what we have to offer to the world and, most importantly, what we believe in.

This interview has been edited and condensed.