Installation as Testing Ground

For Sekou Cooke, a Chicago installation offered opportunities to unite multiple strands of design inquiry.

Sekou Cooke is best known for exploring the connections between hip hop and architecture, producing well-received exhibitions, events, and publications on the subject. But the Charlotte, North Carolina–based designer views this work as only one aspect of a practice that weaves together multiple strands of inquiry and tests them through the process of building.

A project commissioned for the 2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial offered Cooke a chance to assess architectural ideas while helping a neighborhood-focused nonprofit. The League’s Anne Rieselbach and Sarah Wesseler spoke with him about the resulting installation, Grids + Griots.

*

Sarah Wesseler: How did this commission come about, and how did it develop from there?

Sekou Cooke: The biennial, which was called The Available City, was curated by David Brown. His idea was that if you put together all the empty lots in Chicago they would be the size of a typical midsize city in the United States—so there’s a whole city’s worth of land available. And most of those empty lots are concentrated in the more poverty-stricken areas of the West Side and South Side.

He reached out to me with an idea of collaborating with a local organization that had a couple of lots on the West Side, YMEN, or Young Men’s Educational Network. They focus on teenagers, both male and female, teaching them life skills.

The brief was relatively open. At the outset my idea was, how do we amplify some of the things that are happening in the community through this organization? And how do we do that in a way that will feel appropriately temporary for the biennial but still have a permanent resonance in the area?

When we first started talking, YMEN had a 40-foot shipping container on the site that they were using as a bike box. They accept bike donations; they teach people how to repair bikes and lend them out free of charge. They have events to encourage people to bike more. It’s a pretty well-oiled machine.

They’ve also recently added a few other elements to the site—another container for additional storage, a little shed, a covered area, and some planter boxes. They grow a specific kind of peppers that they bottle and sell.

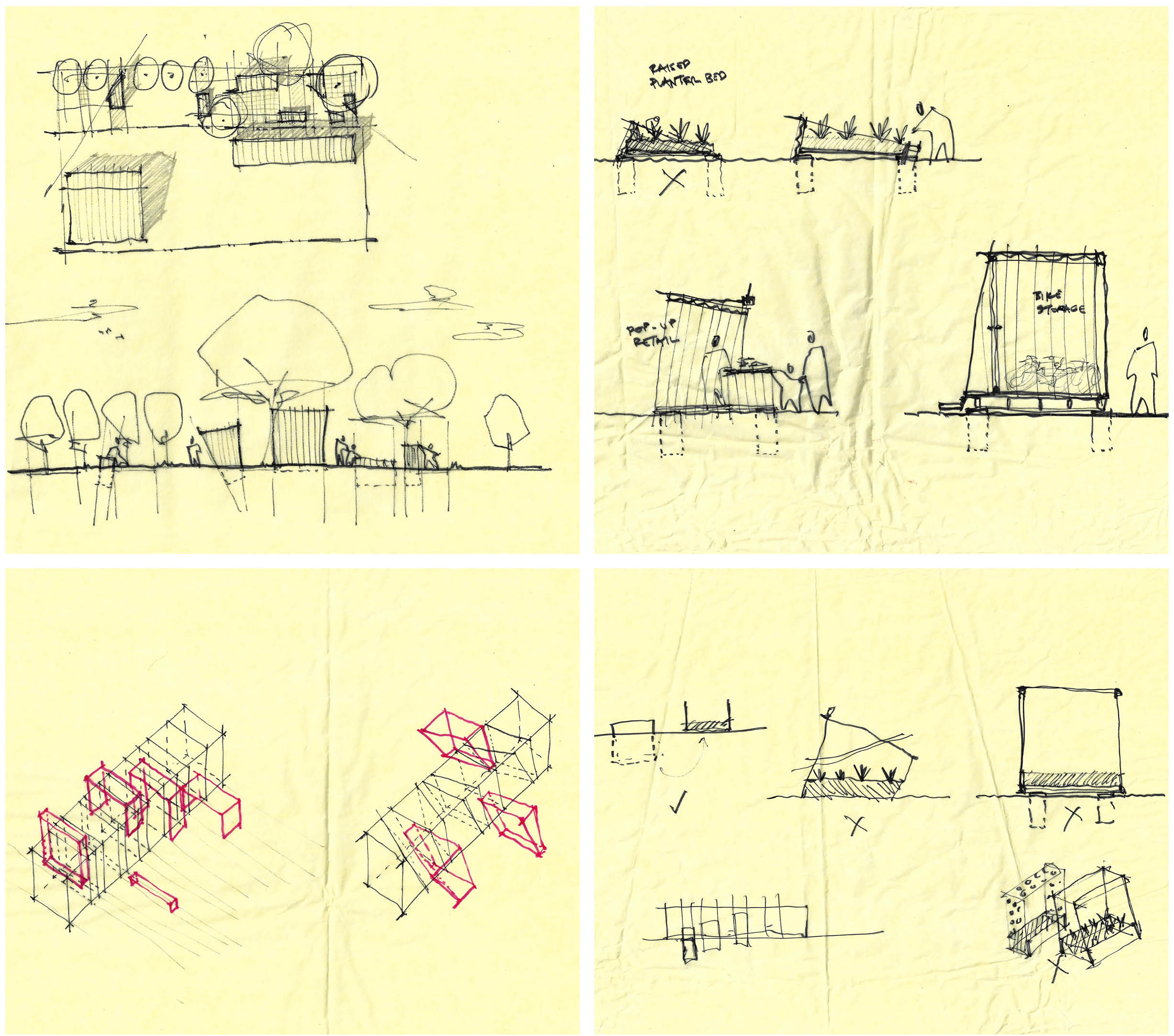

The first idea we sent them was to add another 40-foot shipping container, chopped up. We wanted to use the language of the current landscape rather than bringing in something foreign, transforming and adding new functions to what was already existing. We showed them a few different ways that the shipping container could be remixed, but we wanted to hear from them how this could work programmatically.

The primary organizers, Mike Trout and Marcus Thorne, were interested in having more spaces for bike storage, more plants, seating areas. In our meetings, we talked about how we could create these spaces with a new shipping container and how they could be laid out on the site. They had a lot of ideas about what would work best for their needs: “Well, it’s probably going to work better if we have a seating area here for collective relaxation and conversations; it’s better to move this over here; we could use some more planter beds.”

This project allowed me to try out ideas about new models of working with communities, or, in this case, with local organizations. I’ve been thinking through the idea of community empowerment, as opposed to the typical model that’s called “community engagement.” The basic concept of community empowerment is that by actively involving people on the ground in the design process and releasing part of the designer’s agency to its users, you can achieve something much more lasting.

My relationship with YMEN isn’t that different from a typical architect–client relationship, but they weren’t a typical client, and I wasn’t a typical designer. They wouldn’t normally have had that kind of agency in what would happen in their neighborhood.

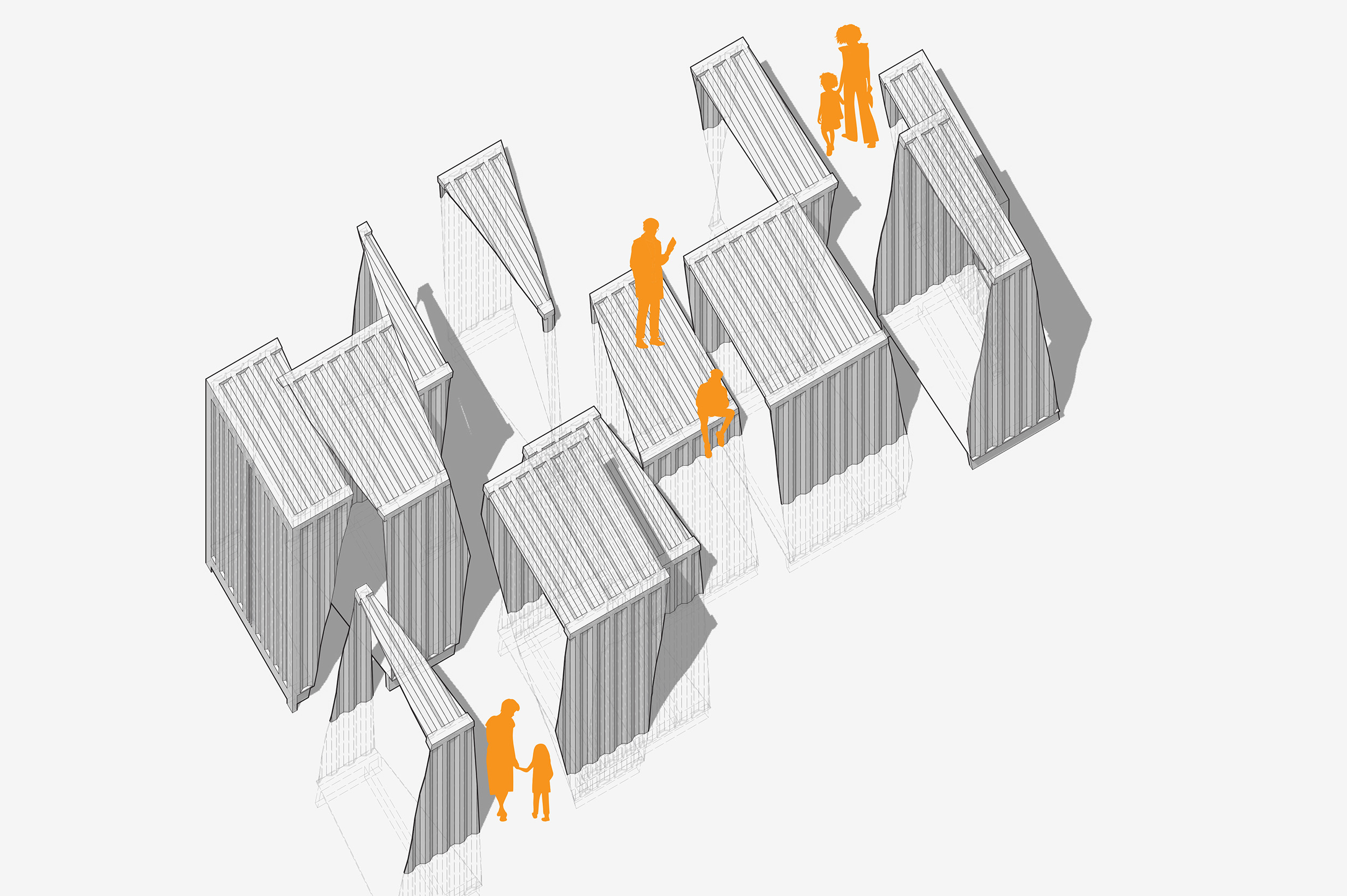

Grids + Griots. The colors used in the installation were drawn from a palette developed for YMEN's bike box by graphic designers at the School at the Art Institute of Chicago. Image credit: Nathan Keay

Wesseler: Can you say more about the dominant model of community engagement and why you think it’s ineffective? And is this something you see primarily on an official RFP level—“designer shall hold X number of community meetings,” etc.—or do you think it’s something architects have internalized?

Cooke: I think it’s both. I think certain ways of working with communities have become standard processes within publicly funded projects, and architects have also incorporated these ideas into their practices more and more. Which is great in some ways, because 30, 50 years ago, designers and planners would maybe just be working by themselves, and then whatever they made would just show up in a neighborhood—and, more often than not, affect it in a detrimental way.

So legal processes were developed to require basic steps: “Okay, please talk to the people who live in the neighborhoods where you’re working. Help them understand the processes involved, and maybe even listen to their opinions.”

But in practice, the community engagement process is extremely extractive: You’re extracting information from people and not really involving them in the process of design. I can only speak generally, of course, and as an outsider, because I’ve never worked in a corporate architectural practice. But I’ve attended some of these meetings, and what happens is literally, “This is the design we’ve come up with. What’s your feedback?” Or maybe earlier in the process, asking “What would you like to see for your community?” There are usually a bunch of sticky notes on a wall, and the design team starts to group them: “Oh, a lot of you want open space. OK, we’re going to put some green stuff on our drawings when we go back to the office.”

What I imagine instead is actually empowering communities to participate in the process of design by saying, “This is how we are looking at transforming this site. How would you do it differently? What tools can we give you to imagine how the space gets shaped? Can we bring you into our office while we’re working and actually see you as part of the design team?”

Because of the short timeline for this project, I couldn’t test those ideas to the fullest. But I worked with YMEN all the way through the design process, talking to them about the programming—how the installation would be used, their ideas for transforming the site—so that their voice was really prominent as the design progressed.

Another aspect of community engagement I’m interested in is getting people’s hands on what’s being made. For this project, we involved not just the YMEN organizers, but also the kids they work with, who were each paid $50 a day for three days to work on the installation. So now when they pass by the piece, it’s not just “Oh, some cool designer came in and did that.” Instead, it’s “I worked on that.”

Anne Rieselbach: How do you think about this project in relation to your other work, particularly in terms of its spatial, tectonic, and decorative strategies?

Cooke: This project is one outcropping of a line of research that began in 2017, when I started doing 3D Turntables. For that project, I began hacking 3D printers by disrupting prints as they came out of the machine.

Sekou Cooke discusses his 3D Turntables project for Technology | Architecture + Design (TAD) Journal.

The formal and procedural language developed through that research has produced drawings that were in different exhibitions, and then started to suggest the formal language of ADUs [accessory dwelling units] that I developed for Los Angeles. It also came out in this project.

There’s an element of dynamism when you’re in the installation; you can sense movement. I think that’s a byproduct of the process of getting to this design: the conceptual chopping and shifting as well as the actual physical chopping and shifting. It was really important to me that it wasn’t just about building something that looked like it was chopped and shifted, but actually taking a shipping container and chopping and shifting it.

I see a lot of my projects as test beds for larger ideas and larger conversations. This one was a combination of three or four different ideas. The formal language from 3D Turntables is one and the community empowerment approach we talked about is another. I wrote a chapter in my book called “Grids and Griots,” and I worked with shipping containers in 2018 when I did the Close to the Edge exhibition at the Center for Architecture in New York. So this project continues those investigations.

But I don’t think I have a singular spatial, tectonic, or decorative approach. It might sound idealistic, but I believe that I really approach every single project with beginner’s eyes. First, I always want to find out what a project is about. The next step is usually thinking about whether there’s a clear conceptual thread that connects to the other research I’ve been doing, or to other projects.

But sometimes there is no direct connection. I’m designing a house right now near Rochester, New York, where the owner wants to use Tesla Solar Roof tiles and a Tesla Powerwall. This will be one of the first projects that uses that technology in that kind of climate, so there’s a whole new line of research into environmental systems happening that doesn’t necessarily connect to my other work.

Wesseler: You said that YMEN had strong thoughts about the program and spatial strategy for this installation. Did they also weigh in on the aesthetics?

Cooke: They weren’t really invested in the formal language. I think they were fascinated by the ideas behind it and glad that I was being upfront about where they came from. I was having conversations with them about griots, about hip hop. We talked about how in architecture, the grid is usually perceived as this completely banal organizational tool, but in reality, it’s quite oppressive. My argument is that every interaction the Black body has had with the grid in this hemisphere has been a violent one, starting with the slave ship galleys, where people were organized and packed in for efficiency, right through to public housing and prisons today. They’re all oppressive structures built for efficiency and based on the grid. It’s a tool that seems neutral, but it actually separates us from our basic humanity.

And then there’s the griot figure, which is the antithesis of that. In West Africa, griots were storytellers, entertainers, sometimes faith keepers or healers, but always keepers of a community’s oral history. In various texts around hip hop, that figure is a model for the DJ: the cultural knowledge keeper in hip hop culture. The DJ knows more about music than anybody else in the room.

So when the griot comes up against the grid, there’s going to be a shift in attention, and distortions of the grid—things that we can’t quite predict, but that are always in response to a more humanistic reading of the grid. And of course, Chicago is one of the quintessential gridded cities.

When I talked about these ideas with YMEN, they were like, “We respect that, we understand that. This is something that we want to see incorporated within the project. And we’re gonna respect your space as the artist.” They wanted to preserve that vision, but for them the functionality of the installation was more important.

I think functionality, in particular, is where there’s a lot of space for more community empowerment in architecture. As architects, we often become protective of our process because we think we’re going to lose control of the design vision. But I think we can preserve that vision while allowing additional voices in the process of determining what we’re making and how it works.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Nothing Spectacular

With an ambitious project in southern Florida, Germane Barnes is helping a neighborhood envision a better future.

The Menu of the Day

For APRDELESP, running a network of commercial and cultural spaces in Mexico City offers the chance to rethink design practice.

Designing Through the Lens of Culture

For Studio Zewde, the process of learning about the communities it serves is a creative act in its own right.