Form, the elephant in the room

Garrett Ricciardi and Julian Rose want architects to rethink their role in society.

Formlessfinder is a 2020 League Prize winner.

Garrett Ricciardi and Julian Rose founded Formlessfinder in 2010. The practice aims to expand architecture’s scope by bringing uncommon materials and processes into the discipline.

The League’s Catarina Flaksman spoke with them about their work.

*

Many of your projects deal with waste. How is this approach related to the environment and the climate crisis?

Rose: Our interest in waste comes partly from pragmatism, since a lot of architecture’s price tag comes from material, shipping, and labor costs. And that’s true whether you want to end climate change or just build in the most efficient and effective way possible.

Our name and our ethos as designers come from the idea that form shouldn’t be our primary concern. In school and in most of the offices we work in, architects are trained to think that we’re supposed to show the world what we can do by inventing something that looks new. And, of course, that attitude is reinforced by the way architecture is usually talked about, and by how it shows up in newspapers and magazines or on social media.

This is way bigger than any particular style—it’s true whether someone is using the latest software to make a complex shape that wasn’t buildable before or pushing a material like concrete or glass to its limit to produce the most minimalist geometry. Even when architects aren’t talking about it, form is the elephant in the room.

So part of our interest in waste came from the desire to engage with the times we live in responsibly, but also from realizing that many of the existing channels for architects to engage environmental problems—whether we’re talking about “green design” or LEED certification—still aren’t getting to the root of the problem. Often they’re literally superficial, and as a result they tend to boil down to style and aesthetics, to rhetorical gestures that are meant to broadcast a certain attitude but may or may not actually be the best way to address the issue.

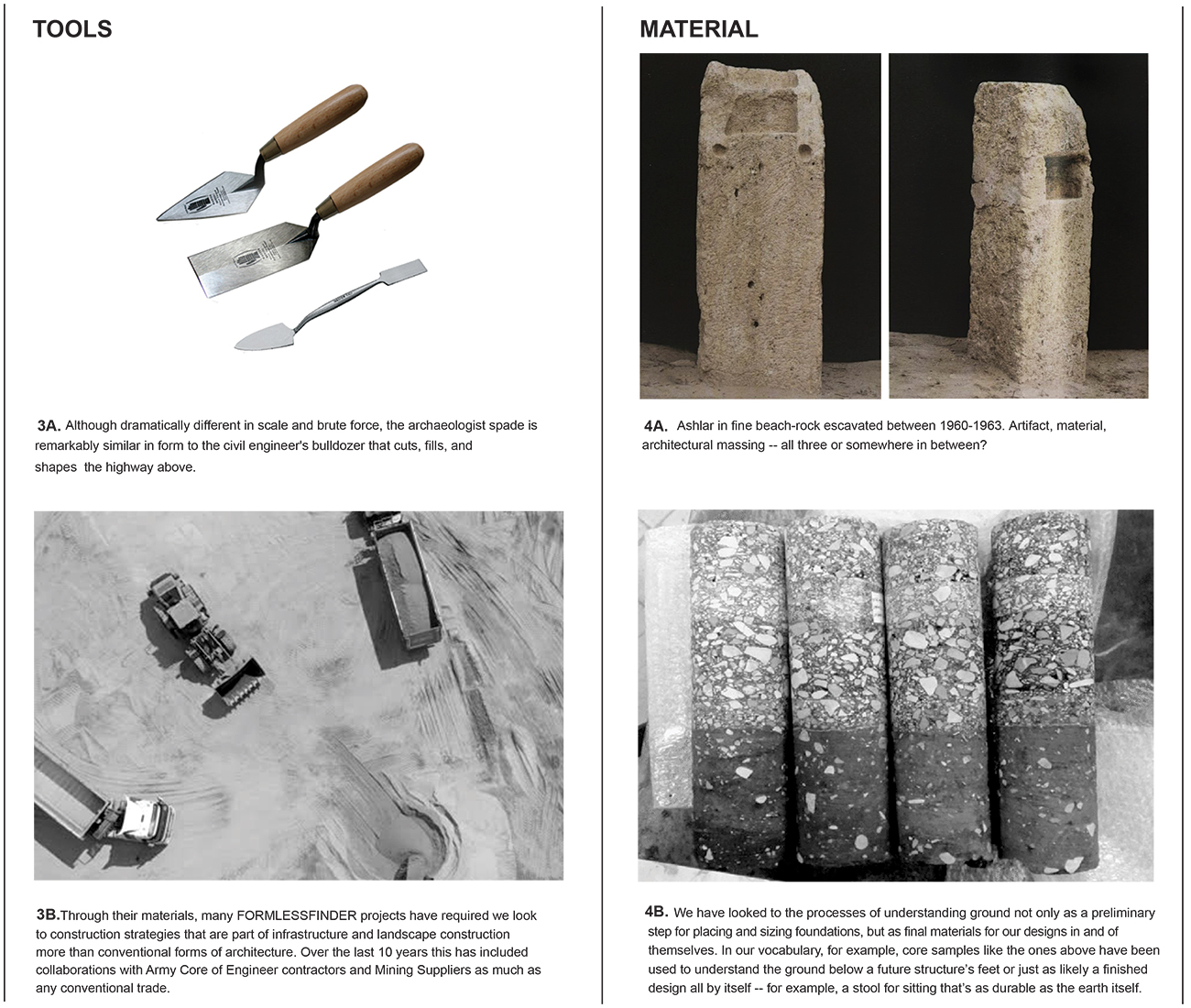

I think that sometimes the most productive solutions aren’t apparent to the casual onlooker, because they’re rooted in the behind-the-scenes processes of architecture. The questions they ask may seem really basic, but that’s the way to get to the big picture: where do the materials come from? How much work will it take to put them together? What can be done with them if they will eventually need to be disassembled? And so on. We’re more interested in thinking through those processes and designing with them than we are in sketching a shape and then trying to figure out how it will be built by reverse-engineering, which is how you’re often taught to work in architecture school. That’s what a charrette is. There are so many more exciting possibilities that open up when you design through the process rather than the other way around.

Our work with food waste grew naturally out of ideas about building waste and materials. In our conversations with the team at Blue Hill when we were designing WastED, it became clear that a lot of what’s considered food waste is still edible. There’s nothing inherently wrong with it, but for various cultural and aesthetic reasons it’s considered useless.

One of my favorite things on the menu was a dish made from scraps from one of the best pasta makers in New York. When you trim a sheet of pasta to make noodles, you end up with all kinds of weird little shapes. These are literally the same thing that customers are paying top dollar for—it’s the exact same dough with the exact same ingredients—but because they don’t look the way pasta is supposed to look, they normally get thrown away.

We’ve been able to find similar ideas in our work with architectural materials. It’s not necessarily about recycling—it’s about taking a new look at the stuff lying around us that no one has thought about using.

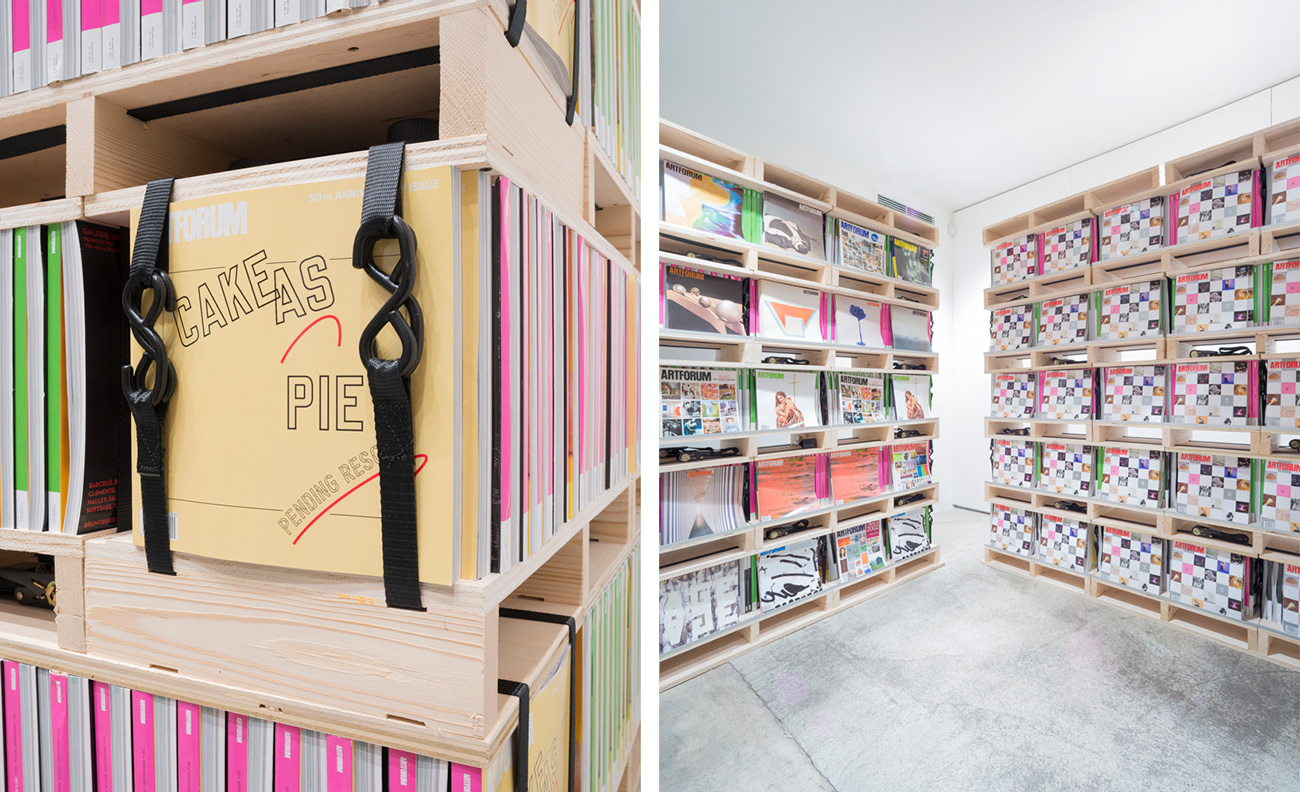

Ricciardi: This manifests in a nice way in the Artforum bookstore project. We were approached to design a bookstore for the magazine in Dover Street Market’s Lexington Avenue space. The budget was very low, but then we found out that Artforum had unsold issues that it was paying to store in a warehouse—it’s actually common for us to analyze a client’s waste streams as part of the research phase of our design, and it’s surprising how often we can find viable building materials. So we took the magazines out of storage and built the bookstore structure out of them.

The system we developed was engineered for pure compression and could be stacked like bricks—we call it magazine masonry. And in many ways it’s closer to the kind of masonry system used for the building Dover Street Market occupies, the original New York School of Applied Design for Women, than the ones architects use today, which are often just brick veneers over a structural skeleton made of another material.

If you look at the project’s material cost, the magazines sell for $15 an issue and we needed about 75 issues per foot, but we got them for free. So in the end you’re talking about a material that’s more than $1000 a square foot, and a project that was completed for less than $10 a square foot.

We’re very interested in those strange things that can come out of reshuffling supply chains and rethinking the use of materials.

In your League Prize competition entry, you talked about the idea of searching for new sites for architecture, thinking about the links between design, infrastructure, and natural resources. Can you say more about this concept? How does it relate to your interest in waste?

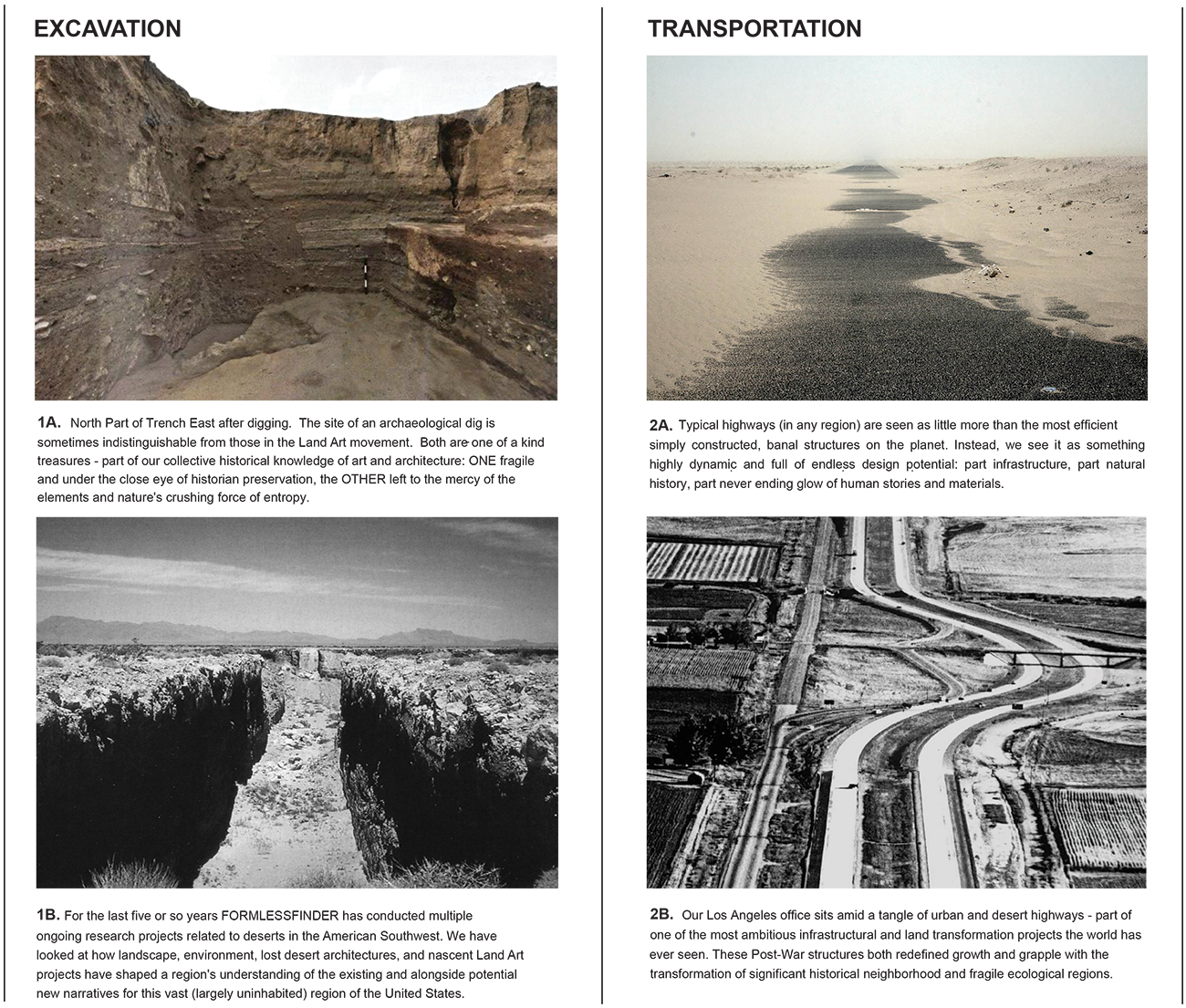

Ricciardi: Well, through Tent Pile, the project we did in Miami, we found ways to rethink the concept of local architecture in terms of a site and its natural resources, starting with material instead of shape or style.

There is an older paradigm of regionalism being stylistic. An architect from North America or Europe building in, say, South America would look to the formal qualities of vernacular architectures in the region—ornaments, roof profiles, etc.—and try to incorporate those into a new design. Even today, when there’s a lot more lip service paid to sensitivity to context, it seems like architects have just gotten really good at producing an image of the local for a global audience.

In Tent Pile, we started to develop a different idea of local architecture: creating a building prototype that uses a specific local material. After we understand how a given material works in a particular context, we can start looking regionally or globally to other areas where that material is available and begin to think about adapting our idea to those areas. So, in a sense we’re trying to do the opposite of bending a global style to a local context—we want to discover possibilities locally first, and then think outward from there.

Rose: Miami is a great example, because if the sand hasn’t been sourced locally, it wouldn’t have been feasible to build the project.

But when we think about sites for architecture, it’s not just in the literal sense—it’s also about looking at the broader cultural and economic landscape we’re operating in and trying to figure out how architecture can contribute.

We all know the statistics about how few buildings are actually designed by architects today. For complex reasons, architecture has become a very refined kind of cultural production. Most of the big decisions that shape our built environment happen independently of architecture.

This gets right back to our problem with form. We’re not arguing that there’s anything wrong with form per se, or even that making form isn’t an inherent part of architecture. But we don’t like the idea that architects are supposed to just make form. That feels like a retreat, even a surrender. Form is like the consolation prize architects have been given for admitting that what they do doesn’t matter.

We really believe in what architecture has to offer, and we believe in the ways that architects are able to think. You’d be hard-pressed to find any political, economic, or social problem today that doesn’t have some spatial and material dimension. That’s not to say that it necessarily has a purely spatial or material solution—architects can’t save the world single-handedly—but we do think that the discipline could have more agency.

So part of what we’re doing is looking for these new sites for architecture in order to expand the scope of the discipline. That’s where our interest in infrastructure comes in, too—it’s often extraordinarily tough and unbelievably cheap, from a cost-per-square-foot perspective, because it has to be constructed at enormous scales in all kinds of challenging environments. Those are the kinds of qualities that can expand architecture’s possibilities.

Ricciardi: Look at sand, for example—by volume, it’s one of the most consumed materials on the planet, second only to air and water. And almost 90% of that sand goes into architecture and infrastructure, embedded in concrete.

In the Middle East, where you’d think it would be easy to build with concrete because of the vast quantities of available material, the local sand is not appropriate for concrete because of its specific texture and grain size. So, by necessity, materials have to be shipped thousands of miles across the ocean in order to build buildings and highways.

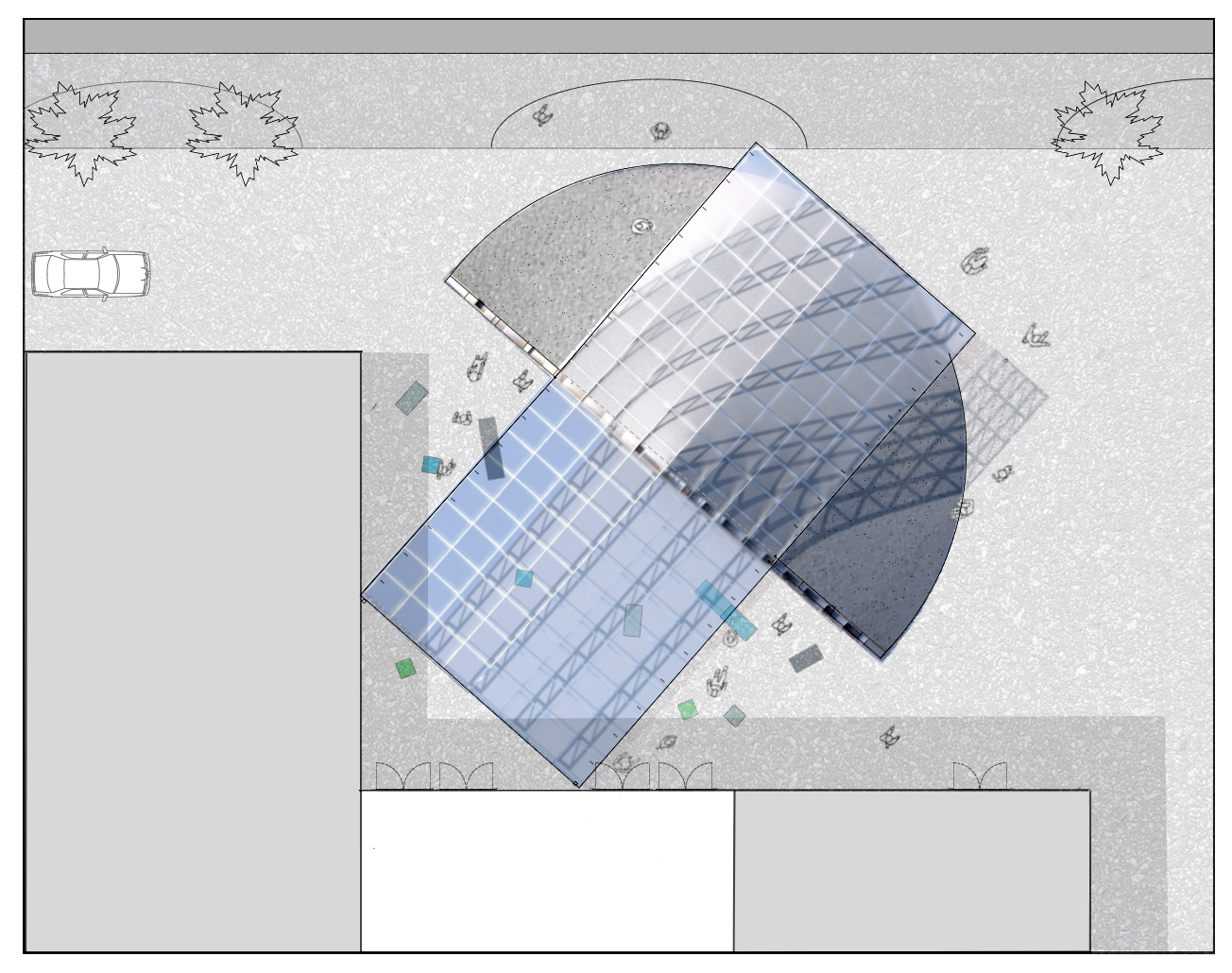

With this in mind, for the Kuwait Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, we are proposing to create sand-based structures in a way that doesn’t trap the sand in concrete, but instead digs down into the desert and leaves it as a lose raw material. We’re proposing to make space by subtracting sand from the landscape instead of adding it to make solid structures.

We’re really interested in these flows of material and how they relate to new ideas of form and can create new economies.

Sabbiyah Highway Archeology and Infrastructure Research Center. Kuwait Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2020. Section (left) and plan views. Images courtesy Formlessfinder.

Most of your projects are temporary installations. How do your ideas about formlessness relate to permanency and durability in architecture? Do you see yourselves building a permanent building in the future?

Ricciardi: Of course. The fact that most of our projects have been installations is partly due to where we are in our career, for sure.

The Kuwait proposal is interesting because it’s a speculative project that uses the materials we’ve experimented with in smaller built works, like Tent Pile, but looks to deploy them at a much larger scale. From what we learned in constructing Tent Pile, we know that our Sabbiyah Highway Archeology and Infrastructure Research Center proposal could be built cost effectively for what’s considered typical in museum or civic building construction. In a way, it’s taking the value proposition we put forward in the Artforum bookstore and finding a way to play that out across 500,000 square feet.

We’re also working on a number of residential commissions, and it’s been interesting to think about how our idea of formlessness fits in there. Sometimes it may be incorporated at the level of the detail, and other times at the scale of a building’s connection to the landscape. One of the first residential projects we had was a commission to build some furniture, and the client very specifically said, “We don’t want sand in our bedroom!”

That’s a great anecdote. Can you talk a bit more about how you communicate your ideas to clients who may not be familiar with debates within the design community or spend much time thinking about architecture’s role in the world? Do you find that people get what you’re talking about right away, or does it take some convincing?

Ricciardi: Well, we want the work to operate on both levels. For Tent Pile, on the one hand, we could write a whole architectural history of sand, going all the way back to how Egyptians used enormous sand ramps to erect their obelisks, or we could have a theoretical discussion about the iconicity of raw materials in projects like Claude Ledoux’s Les Salines Royales. But on the other hand, Tent Pile just provides a mound of sand to play on, like a sandbox or a beach. There’s a real immediacy and playfulness to what is possible with the formless.

We enjoy the full spectrum of potential engagement—the easy, tactile side as well as the disciplinary, historical side.

Rose: Your question gets back to the League Prize theme of value—what we think value in architecture is, and how we hope our projects offer value. We have a deep interest in the history of our field, but we don’t believe that our projects should live or die on intellectual or conceptual terms. With our interest in formlessness, we obviously enjoy playing devil’s advocate, but we also do genuinely believe that it’s a useful way to think about how architecture meets the world, and what architects’ goals should be.

One reason we found the League’s call for entries so provocative this year was that you pointed out that there don’t seem to be many shared values in architecture today. In that sense architecture probably mirrors culture at large—it’s very fragmented. But this got us thinking that in the absence of a clear consensus within the discipline about, say, why architecture is important or how it should be designed and built, there is another value system that rushes in to fill the vacuum: market value. Many of our projects seek to somehow subvert the market forces that typically shape architecture with the goal of opening up alternative choices. That might sound academic, but actually we hope the logic driving our projects could be understandable to anyone. A client shouldn’t need to know anything about the history of architecture or the theory of globalization to understand that if we can build 80% of the building with sand that’s already onsite, it’s more practical and efficient in a way that opens up new possibilities.

Ricciardi: We’ve certainly placed value on experimentation over professional practice, in a sense, but we do seek to balance the two. That’s what we find interesting and challenging about the formless: taking concepts that are seen as outside of architecture, or materials seen as outside of architecture, and finding ways to bring them in. And as part of this, explaining these ideas to people in ways that also gets them excited.

We did end up using sand for that client’s furniture after all. It was in a vacuum-sealed bag, but we were able to convince them, at the end of the day, they needed a little bit of sand in their bedroom.

Interview conducted on May 22, 2020.

Edited and condensed.

Explore

Anna Heringer: Sustainability=Beauty

The German architect speaks about her love of mud as a building material.

Empowering architects to take on carbon

The design community needs a robust toolkit of decarbonization strategies that all practitioners can use, argues KieranTimberlake's Stephanie Carlisle.

Mexico’s Traditional Housing Is Disappearing—and with It, a Way of Life

Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Onnis Luque are fighting to preserve their country's vernacular architecture.