Interview: Estudio Macías Peredo

Emerging Voices 2014

Estudio Macías Peredo

Salvador Macías Corona and Magui Peredo Arenas

Salvador Macías Corona and Magui Peredo Arenas founded Guadalajara-based Estudio Macías Peredo in 2012 with a focus on design and construction, embracing a critical regionalism in which the craftsman is part of the building process. The firm has designed residential, commercial, and institutional projects across Mexico that combines the local and the global to create a timeless architecture that makes the vernacular contemporary while exposing the handcrafted materials. Their projects include residential projects Casa Arenas in Guadalajara, Casa Atlas in Zapopan, and Casa Prado in Tapalpa and commercial projects Oficinas Casa Hidalgo in Guadalajara and Oficinas Toyo in Zapopan. The firm also won the Pabellón Eco 2013 competition at the Museo Experimental El Eco in Mexico City for a temporary installation to make a courtyard into a public square. Work in progress includes Mendoza Dwellings apartment building in Zapopan, Casa Chacala in Chacalilla, and development projects for Rancho los Venados in Acatic.

In March 2014, on the occasion of their Emerging Voices lecture (video embedded below, also available here), Macías and Peredo sat down with League Program Director Anne Rieselbach and Program Associate Jessica Liss to discuss their practice.

Jessica Liss: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Magui Peredo Arenas: Our voice is the voice of our conscious. We have a voice that is constantly reminding us where are we from, and what is possible in our context. We are always talking about our context because we have mainly worked within our city, Guadalajara, Mexico, and its surroundings. The ways there are very defined. Our work tries to give continuity to processes and practices from our local traditions, more than a singular voice or a singular vision of architecture.

Salvador Macías Corona: People from Guadalajara are more traditional than people from many other big cities. This can be a good or a not so good reality, because the traditions of construction and building do not change much. Our voice is to take these existing conditions and realize new visions, making something with manual labor that is practically extinct today.

We are living in a world in which it seems that architecture can no longer be made brick by brick — but Magui and I are always trying to. In our city it’s a totally different condition, and for us it makes a great difference.

Laying handcrafted brick | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

MP: Although our city is the second most populous city in Mexico, the profession of architecture is still very linked to the idea of construction. We realized that if we wanted to have a presence as architects, we needed to start by being builders. This was a whole new type of schooling for us. We learned from construction to experiment, to be creative, and to give the time necessary. We work outside a lot, next to the artisans. Our role as architects is to establish some rules, and then allow skilled builders and artisans to interpret those rules through our drawings. There is a lot of improvisation and openness; we’re okay with letting go.

SM: In other places these experiments might not be possible, either due to regulations or lack of interest from clients. Despite being traditional in some respects, it’s a place open to experimentation, most significantly in the construction processes. I tell my students that in Guadalajara, architects are more builders than architects. They may spend around 80 percent of the week at the building site; architects are on site more than in an office.

Using steel frame with handcrafted brick at Casa Atlas | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

JL: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practicing in today’s economic, professional, and intellectual climate?

MP: We live in such a tumultuous world that we believe architecture must always be adaptable. We try to do things that are very flexible, that can change a lot. The economy plays a big, big role in our work. We’re of course always trying to put forth a solid architectural idea, but the reality is: how are we going to build it, how are we going to finish it on time, how are we going to meet the client’s budget? You always have to adapt, but especially in this time.

SM: I think that architects all over the world need to be able to adapt to varied global conditions. We worked with Carme Pinós, who has the flexibility to move from Austria to Guadalajara, which we view as an imperative for making architecture now. Our city will always be important to us and we will continue to work there. However, Magui and I speak all the time about seeking opportunities to learn and develop our work in different contexts.

MP: We’ve been isolated in a city that really has defined us, and shaped the way we view and practice architecture. We wonder what our work will be like when we start to do projects, we hope, somewhere else.

JL: Tell us more about your emphasis on the importance of craft and handwork.

MP: Guadalajara is a land of artisans, and this includes construction. It’s a real tradition; there are families of carpenters, towns of ceramicists. We embrace the notion of construction as craft, and it’s very defining to what we do. We find it very difficult to embrace architecture that’s neat or perfect. Imperfection and the imprint of manual labor are fundamental to our work, and we love it.

Our dream project is to build ruins. There’s imperfection there — they show what they are made of and there’s no adornment. There’s such honesty behind a ruin. We would like to make architecture that has that kind of essential exposure, when only structure and space remain. To expose craft is a method to show time. As time goes by, age becomes very apparent.

Terraza CV under construction | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

SM: We try to show the processes of the labor and the materials. The mason’s hand cannot build perfectly polished walls. But when a mason polishes a wall, the textures left behind are more interesting. We feel that these things are important, that the making process should be revealed in architecture.

MP: Craft is not a nostalgic theme for us; it’s a condition. There is a lot of creative opportunity in this approach. Our office is very hands-on — we do lots of modeling first, and the images come later. We have a huge table where we’re doing, doing, doing all the time. It’s a small-scale version of the building process for us, in which we experiment with textures and scale. The craft comes not only on the construction site, but in our office as well.

Oficinas Casa Hidalgo during renovation and construction | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

Completed Oficinas Casa Hidalgo | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

JL: You describe your firm as, “In a balance between the understanding of our regional situation and the needs and aspirations of present architecture.” One of the ways that you bridge that gap is through your yearly international field studies. How do you incorporate what you learn through travel into your working process and finished projects?

MP: Every year, for six years now, we organize an international study trip. We’ve visited Brazil, Portugal, California, Chicago, Peru, and various regions of Mexico. Our next trip is to Japan, and we’re going with 36 architects from 20 to 60 years old. We look at ourselves as permanent students of architecture, so we really take this seriously. We are in Guadalajara, and always studying Guadalajara, but we force ourselves to leave our city because we need that balance.

When we travel, it’s the spatial organization of the buildings and their relationship with the site that we study, less how they’re actually constructed. We take these ideas home and our job is to figure out how we can achieve the same solution with our artisans in the building process.

Mies van der Rohe once said that he really loved to teach because that was his space to reflect about architecture and problems related to architecture. When a project came into his office, he wouldn’t have time to think, he just had to do. We share that feeling — our moments of studying, reflecting, and analyzing architecture come through teaching and on our trips. When clients come, they don’t come for an architectural idea, they come with “I need to build a house” or “I need to build an office.” That rush doesn’t let us think about the ruins, for instance.

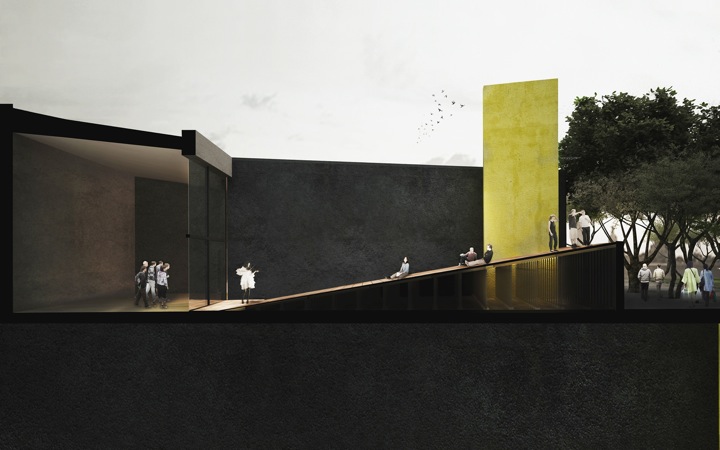

Juxtaposing traditional and modern | Rendering courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

JL: You submitted your Emerging Voices portfolio on textured illustration paper inside a wooden box. We viewed that as an acknowledgment of the importance of texture. Could you talk more about the choice of materials in your work?

MP: Our material choices are very closely linked to the structure of the project. We don’t choose materials to be coating or cladding — they work structurally or architecturally. We do very few coverings, so what you see is what it’s made of.

Casa Arenas | Photo by Jaime Navarro

Casa Arenas, a one-story house for a retired couple, is a great example. We got these very small steel chips, excess pieces from car mechanics, and we gave them to the masons to mix with concrete and other materials to create a sort of plaster. The walls are actually stained by the process of oxidation and then sealed. The oxidized steel chips might be considered a coating because there’s regular brick beneath, but by using this coating we hope that the owners would never feel the need to paint the brick. It’s integral.

SM: We don’t really like the industrial, pre-fabricated brick that most houses under construction use. Each one is the same, and it’s very repetitious. So instead we prefer to use handmade brick, from artisans that specialize only in brickmaking. With Casa Atlas, the neighboring houses use brick as a facade, as covering. Casa Atlas is the only house that uses traditional local brick. How come nobody else used it?

Casa Atlas in Zapopan, México | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

MP: We love the contrast between rough and refined materials. You can see the perfection of the steel structure against rough carpentry, with each one of these elements cut, shaped, and accommodated on site. That relationship strengthens the voice of the other material. The perfection of the steel frame speaks to the imperfection of the brick, and makes it more evident.

SM: Our clients for the CV Terrace don’t like modern architecture like Mies van der Rohe’s. Yet the space in the CV Terrace mimics his use of space — it’s a clear span, a continuation of landscape. The services are placed in boxes, and, just like the Farnsworth House, they never reach the ceiling. But we used stone and wood instead, and just by changing the materials and the construction system, these clients feel more comfortable with the spatial organization. They forget about Mies.

Terraza CV in Zapopan, México | Photo by Jaime Navarro

JL: You won a competition in 2013 for your Eco Pavilion at the Museo Experimental in Mexico City. What was the goal of this temporary installation?

MP: With our intervention, we wanted to highlight an existing condition that visitors had likely never paid attention to — in this case, the clay floor of the courtyard. The museum was designed by Mathias Goeritz, a German artist who lived in Guadalajara and Mexico City. He was a very close friend and collaborator of architect Luis Barragán, and you can see Barragán’s influence. The building looks so contemporary that you can’t tell it’s from 1953. The clay floor, one of the only surfaces that isn’t painted, is the only material that expresses the real age of the building.

We found a vendor for the same clay tile that Goeritz used, and built a sloped floor over the existing tile in the walled outdoor courtyard. The new sloped plane started at the gallery level of the museum and reached the low wall that separates the courtyard from the street, blurring the boundary between the museum and the street.

Model for Pabellón Eco 2013 | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

Finished installation of Pabellón Eco 2013 | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

Across the street there is a big park with a popular arts and craft market and tons of people, and inside the museum, which is free, you usually find few people. So with this gesture, connecting the institution to the public realm, we’re saying, “Why don’t you come in here?”

JL: That Pavilion, where you reinterpret the museum as open space, speaks to the tension between solid and void that exists in many of your other projects as well.

MP: We love patios — we try to put them in our buildings as much as we can. When we want to open architecture to an exterior, we need it to be an exterior that we have built and controlled. That’s probably a very Luis Barragán lesson that we follow as much as possible.

We’re more void builders than solid builders — we build the voids and then have the solids relate to them.

SM: In a ruin, the ceiling has fallen and you can see trees between the walls. The definition of space, between indoor and outdoor, is no longer clear. The intention with this house is to remember that condition. The relationship between spaces in Casa Atlas is similar to a ruin. The lack of distinction between inside and outside makes it more comfortable and strengthens the relationship between the house and the trees and plants.

MP: The site was a very narrow plot of land without vegetation; we needed to build a garden to make the site work. When our photographer, Jaime Navarro, was photographing the house, he said, “I’m not going to charge you anything for this. You can’t see the house in my pictures, only the garden.” And we said, “That’s what we wanted, that’s our ruin.”

Gardens at Casa Atlas | Courtesy of Estudio Macías Peredo

***

Salvador Macías Corona and Magui Peredo Arenas, Estudio Macías Peredo,Emerging Voices 2014, complete lecture video | Recorded March 27, 2014 | Running time: 36:49

***

Both Macías and Peredo earned their architecture degrees from Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO) in Guadalajara and graduate degrees from Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) in Barcelona. Macías participated in 2008 in the VI Ibero-American Architecture Biennale in Lisbon and in the international exhibition44 Young Architects in Barcelona. Peredo has lectured at institutions across Mexico and her research, “Herbert Bayer and Mathias Goeritz, New Monumentality in Mexico,” has been featured in several architectural forums. The two currently teach at ITESO.