Lower Rio Grande, New Mexico

Searching for Her Roots in the Borderland | Doña Ana County

In this interview, Lucia Veronica Carmona shares her courageous journey searching for her roots as a Mexican fronteriza (a person who lives on a national border). Her search took her across rural Mexico, where she learned traditions from local elders; brought her back to the border, where she worked as a lead organizer for the Colonias Development Council; and has ultimately materialized in the work she leads at Raices del Saber Xinachtli Community School, a charter school for kindergarten through fifth-grade students that uses Mesoamerican Indigenous concepts in its curriculum. In May 2014, she became a W.K. Kellogg Foundation Fellow as part of the first class of the organization’s Community Leadership Network program.

Carmona sings traditional Mexican music, and in this interview shares a song in Nahuatl, English, and Spanish that was recently taught at Raices del Saber Xinachtli Community School. —Ane González Lara, Diverse Peoples, Arid Landscapes, and the Built Environment report editor

Lucia Veronica Carmona. Video credit: John Acosta

Ane González Lara interviewed Lucia Veronica Carmona in 2020.

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

Ane González Lara [AGL]: How did the border play a role in your search for your roots and identity?

Lucia Veronica Carmona [LVC]: My journey in search for my roots and identity is a long one that started with my awakening in my early youth years.

I was born in Ciudad Juárez. My grandparents arrived to Juarez from the Sierra Tarahumara, but growing up, I never had a sense of my indigeneity, and I was never encouraged to learn more about those roots, probably as a mechanism to survive in the city. Being assimilated was a way to survive in the border, so I was never encouraged to look like “los indios”1the Indians, with a pejorative connotation.

Unlike the women before me, I was very fortunate to attend middle school. When I was 15, I worked at the maquiladoras2factories while going to secundaria3middle school in the evening. If you wanted an education, your schedule consisted of going to work from six to three and to class from five to nine, every day of the week.

Unfortunately, I lost so many great teachers that I had during that time, the ’70s, just because of their ideologies.4This refers to the Mexican Dirty War, a period of internal conflict between the Mexican government, under the single-party rule of the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), and left-wing student and guerilla organizations. Learn more here. These teachers shared with us messages of freedom, of being your authentic self, and the experience of love instead of the capitalistically driven consumerism. Losing some of my beloved teachers made a big impression on me, and I started to ask questions about my own roots and origin.

In an effort to gain consciousness of who we were as fronterizos5people who live on a national border, other than just cheap labor, I decided to travel to rural areas of Mexico with a program for adults that defended Spanish as our language. It turned out that I learned a lot from this experience. I learnt many old traditions and knowledge, and I also learned that Spanish was not the original language of my ancestors. This process allowed me to become more aware of my culture, identity, my roots, my great-grandparents, the Sierra Raramuri, and the reasons for discrimination against the indigenous people and mestizos.

When I lived in Ciudad Juárez, I didn’t like to cross the border, and I had no interest in working or living in the US. Eventually, all my family lived in the United States, and I got to spend periods of time with them in the US, but I always felt like that wasn’t for me. Every time I left the border for long periods of time, either to visit family or for adult education programs, I felt the urge to go back to the border region, back to my identity. My journey was almost like a cycle that took me back to my place.

In my search process, I’ve had deep encounters, and I learned that there are a lot of borders: my border in my border town, then the border of discrimination against Indigenous communities, the border of the situation between men and women, between elders and youth, between sick people and healed. I’ve seen and experienced a lot of borders, not only the one dividing the US and Mexico.

AGL: How did you start working as a volunteer on social justice issues that were so critical in the border region at the time?

LVC: When I traveled to rural areas in Mexico, I told the elders that I was looking for my roots. One of the elders once told me: “Mija6The term mija is a colloquial contraction of the Spanish words mi (my) and hija (daughter). Spanish speakers often use mija and its masculine equivalent, mijo, to express affection., your roots are in the place where you come from, they are waiting!” I was looking for my cause, and they helped me understand that my cause was right where I started [laughs].

After going back to Juarez, the violence started to get worse as families and friends got killed. Additionally, after the September 11 events, crossing the bridge daily became an arduous task, waiting more than four hours just to cross. Therefore, I had no choice but to move to El Paso, Texas, where I started a full-time job at a notary public office as secretary to serve immigrant people who were looking for filling out paperwork from the USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services). In addition to my regular job, I got involved as a volunteer in binational projects for human rights, immigrant rights, environmental justice. Without realizing, I started to travel again to other states with that work. I spent four years doing that while I was living in El Paso.

At a certain point, I realized that I needed a bachelor’s degree to move forward in my work, and I went back to studying. It took me more than seven years to earn my bachelor’s degree in sociology. By that time, I was already a single mom, with a full-time job, going to school, and volunteering as a community organizer in different organizations like the Farmworkers Center in El Paso, the Coordinadora Regional Fronteriza (COREF), La Mujer Obrera, Las Colonias de San Elizario, Las Colonias de Nuevo México . . .

In my search process, I’ve had deep encounters, and I learned that there are a lot of borders: my border in my border town, then the border of discrimination against Indigenous communities, the border of the situation between men and women, between elders and youth, between sick people and healed. I’ve seen and experienced a lot of borders, not only the one dividing the US and Mexico. —Lucia Veronica Carmona

When I went to university, I found this book titled Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy.7Barbara Ehrenreich and Arlie Russell Hochschild, eds., Global Woman: Nannies, Maids, and Sex Workers in the New Economy, 1st ed (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2003). That made me understand an internal border that existed between my mother and I. The book is about the women that cross international borders to work, often taking care of children of other families, while leaving their own children alone with friends or relatives, sometimes leaving their kids without them for weeks or months.

I am part of a legacy of single mothers, and in my case I was also a child left alone by her mother to work on the other side of the border. I only knew that I needed my mother, and I couldn’t understand the reasons why she wasn’t there. Without realizing, I had always judged her or held resentment against her because of that reason. I couldn’t see the big picture until I got this book and understood the economic disparities that exist in the border region and the consequent family separations.

In 2004 I moved to Las Cruces, New Mexico, and was invited to work at the Colonias Development Council (CDC). The CDC recruited me as they liked the way I was connecting with the communities when volunteering for a binational organization for human rights, immigrant rights, environmental justice, and many more. Before working at CDC, my community work had always been as a volunteer after my regular job.

Carmona denouncing the streamline operation, the fast-track prosecution of immigrant people, in front of the Las Cruces, New Mexico Federal Courthouse. Protestors had hoped to block buses shuttling undocumented immigrants from entering the courthouse. Photo courtesy of Lucia Veronica Carmona.

AGL: Can you explain what the colonias are and the work that you did there?

LVC: After crossing the US–Mexico border, the first 25 miles from the border don’t have any checkpoints. After that zone, you have to start to cross checkpoints. Over time, many immigrants bought parcels in that underdeveloped zone8According to The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), “Colonias are rural communities in close proximity to the U.S-Mexico border, lacking access to basic services such as water, sewer, or housing.” The lack of socioeconomic data has prevented colonias from getting funding to improve their scarce infrastructure. and brought their mobile homes with them. Most of them were migrant workers from Mexico that moved through the area depending on the crop season and lived in temporary structures. That’s how the colonias9“Colonias History – HUD Exchange,” accessed October 25, 2020, https://www.hudexchange.info/cdbg-colonias/colonias-history/ started to grow, and grow in an unstructured way. As they grew, they also started to mean votes for local politicians that started to pay attention to them.

When I started working at the CDC, they already had 15 years of existence. They were addressing farmworkers’ issues, environmental justice, and economic and infrastructural issues. I met a lot of people and I got involved in this organization for more than eight years.

Every year we worked on different projects, from immigration to environmental justice. We worked against landfills that companies wanted to bring to the region, the contamination of the river. We fought for more infrastructure by getting more roads paved . . . In 2010, two years before I graduated, I got involved in other projects very organically as funds for CDC went down.

AGL: I believe that during this time you applied and got a fellowship with the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to expand your outreach and knowledge. Can you tell us more about that?

LVC: I applied to the W.K. Kellogg Foundation Fellowship with a question that framed my area of inquiry: “How do we overcome intergenerational historical trauma?” I joined the fellowship with the New Mexican cohort. Half of the group was native Native American, the other half Chicanos born and raised in the United States, and two of us were from the border. I was the only fellow that considered herself Mexicana. I presented myself as Mexicana, from the border region and an indigenous person of that land.

During the first day of my fellowship I had two moments of deep realization. The first one took place during one of the introductions. A young indigenous woman from Michigan in her regalia sang in her language and started to speak very proudly about who she was, how she was learning her own history through her parents. She spoke up about the oppression, displacement, and pain of her community. I was mesmerized by the way that she presented herself, so proud of who she was. In that same moment, I realized I wanted that confidence for my young people in Las Colonias. I wanted that for my son. I wanted that for us, for myself.

My second moment of realization was during another presentation. There was a white woman [who] was wearing a huipil10Learn more here. participating as a panelist. When I saw her, my first reaction was, “Who is that white lady portraying herself like a native person?” I was just so skeptical. However, when she started to talk she said that she was Mexican, from Chiapas and white. Because of her skin color, she had been rejected in her own pueblo and she had to work very hard to be able to wear that huipil. She had to demonstrate to her people that she was ready to be the voice of the voiceless. After saying that, she started to present the amazing job that she was working on.

That made me think about all the prejudice that we all have against each other—all those divisions, those borders, again, that we all construct when we don’t understand each other.

When I came back from Michigan I was ready! But where could I start?

Fifteen years before that day, one elder in Jalisco told me, “When you are ready to see, you are going to see. You have to go back to your land where you started.” And so I did. Five days after coming back from Michigan, I met Carlos Aceves, who is now my partner.

Carlos was a bilingual teacher working in Canutillo on a Xinacthli program that he created with other teachers. For 20 years they had been working on that program, introducing Mesoamerican concepts to elementary students. When I met him, he was ready to give up because the administration had decided to stop supporting the program, despite its success. When we met and he told me about the program, it was like magic. I was like, “Oh my god, that is exactly what I was looking for!” Immediately, I asked him if he was willing to bring some of his modules to the parents. And he asked, “How?”

As an organizer, I knew how to bring people together, and that’s what I did. My fellowship mostly consisted in us having conversations with the community about our roots, our background, the knowledge of our ancestors.

At the end of the fellowship with Kellogg, one of the fellows talked about the NACA Inspired Schools Network. NACA stands for Native American Community Academy. NACA’s network was focused on addressing the situation of the Native American students that were out of their reservations or pueblos, living in the city and therefore losing their language, customs, and almost everything. They were addressing this trauma of not knowing who you are, feeling worthless and not accomplished. Some of their students didn’t speak English very well and were illiterate. These kids were falling behind, like our kids in las colonias. NACA used this model of charter schools to bring the language and culture [together to] create a unique space in the classroom and education . . . from pre-K to 12. Right now, they’re in their fifteenth year already, and are being very successful.

AGL: This brings us to the Raices del Saber Xinachtli Community School. Can you explain how you started the school and the work that you do there?

LVC: The process of getting all the approvals was long. We were challenging the entire education system, and we also had to bring evidence that a student exposed to Mesoamerican knowledge would succeed in mathematics, for instance. During some of the hearings we had when we were trying to get this project started, we were asked where we were getting our knowledge from. Because the knowledge we share is coming from our elders’ oral history and it is not necessarily in books, some were challenging its validity. They even asked whether it was legal. There were a lot of things that we had to defend during those days. Luckily, we had testimonials of young adults that had been exposed to Carlos previously, so we used those as evidence. We also started to tap into similar projects in other states and bring evidence based on other projects.

And we made it! We currently have 60 students in our K–5 program. This is our second year of operations. We are building a foundation in the little ones and in their families at the same time. Our current students will eventually become advocates for this kind of knowledge in the public schools and their communities.

We started small and we are slowly growing our roots. The name of the school is connected to that idea of growing our roots. Xinachtli, in Nahuatl, means the transition moment between a seed and a plant. That’s how we see our students. We then added Raices del Saber to the name, which means Roots of Knowledge. Now everyone calls it Raices or Xinacthli.

Currently, in our second year of operations, even with COVID we have a full attendance of 60 students, 20 per grade: kindergarten, first, and second. We also have a waiting list because our commitment is not to have more than 20 students per classroom.

AGL: Can you share some examples of the pedagogy and knowledge that your students receive at Xinachtli?

LVC: Our pedagogy is based on storytelling. We use the Aztec calendar and we talk to students about its relationship with astronomy, mathematics, and many aspects of our daily lives as they relate to the cycles in life, the moon, Venus, and the sun. Every morning, we use the circle to foster a sense of belonging and community. The circle also allows students to learn to listen and be patient and wait until the one with the magic stick or the feather is done speaking.

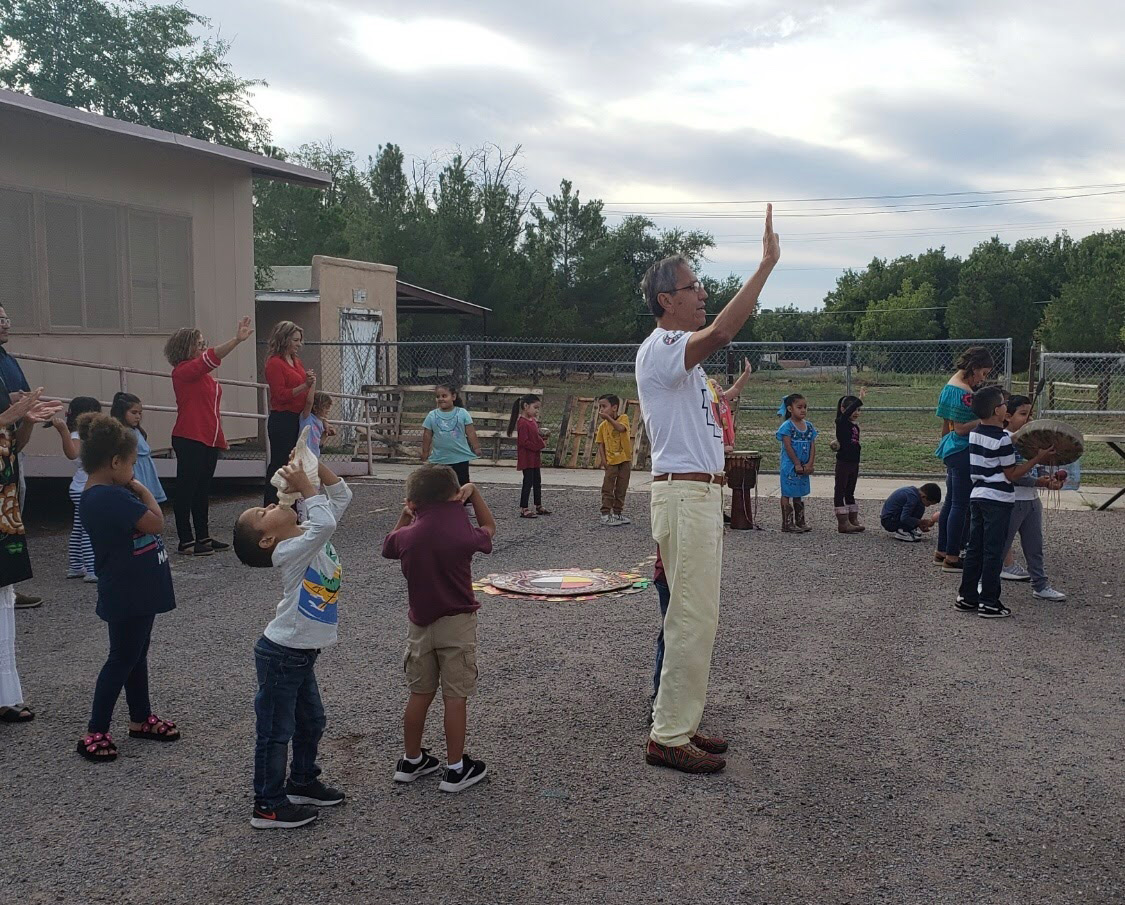

On a regular day, before COVID, the school had a commitment to start every morning with a circle. Everyone in our school—the staff, teachers, and students—saluted the directions. After breakfast at Raíces del Saber Xinachtli Community School, parents, teachers, administrative staff, and students gather outside for a socially centering exercise that involves musical instruments and acknowledgment of the four cardinal directions, the sky above, and the ground below. We face and name each direction in Spanish and Nahuatl, turning in circular motion, announcing a basic fact about each directon. The children acknowledge each turn with drums, rattles, rain sticks, and blowing a sea conch shell. This traditional greeting is part of our Native American heritage.

Right now, with COVID, we are recording and posting in YouTube the modules for our students to watch at home. The name of the channel is Tloke Nauoke.

Carlos Aceves with students, faculty, and staff of the Raices del Saber Xinachtli Community School during their morning gathering, saluting the directions and playing the conch. Photo courtesy Lucia Veronica Carmona.

Most of our students are low-income, and almost 50 percent of our students are monolingual English. This was a surprise for us, because we apply the 90:10 model to emerge students into English little by little: Ninety percent of the instruction is happening in Spanish, and 10 percent in English. The English-speaking students are in a situation similar to a monolingual Spanish student that goes to a public school. However, we provide support to English-speaking students. In most public schools, when Spanish-speaking students join, they are often segregated. They put them in an ELL [English-language learner] group, like someone that is sick or incapable. But in our school we have all students together, including special education students. We have a lot of interactive learning outdoors and hands-on. Nonetheless, the kindergarteners are also performing mathematics of third grade, fractal geometries . . . It’s unbelievable. And their parents are, “Wow! They’re learning about all this!”

AGL: You are a very talented singer, and you’ve used your songs to share the realities of the oppressed. Would you like to share one of your songs with us?

LVC: Yes, this is one of the first songs that our students learn. Our students learn English, Spanish, and Nahuatl, and this song celebrates the three languages.

(Lucia starts playing her drum)

Te cuica ahuiyolame Teotatzin Ilhuicamina (x2)

Tlazocamati Teokiahuitl – Tlazocamati huel miac (x2)

I am singing with all my heart the sky is already crying (x2)

Mother Earth is giving and sharing her precious water (x2)

Cantemos con alegría que al cielo le está gustando (x2)

Madrecita Tonanzin las gracias le estamos dando (x2)

Biographies

is a native of Juarez, Chihuahua, from Rarámuri (Tarahumara) ancestry, and has lived in Las Cruces, New Mexico, for the last 15 years. After immigrating to the United States, she led and participated in different local campaigns and grassroots movements along the border region. Through her social justice work, she became a lead organizer for the Colonias Development Council, board president of the farmworkers Sin Fronteras Organizing Project, and the regional project coordinator in Southern New Mexico for the National Immigrant Farming Initiative.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.