Interview: DIGSAU

EMERGING VOICE 2013

DIGSAU

Jules Dingle, Jeff Goldstein, Mark Sanderson, and James Unkefer of DIGSAU conceive of the architect as a generalist, rethinking architectural processes. The Philadelphia-based practice uses craft and low-tech construction to inform today’s complex computational and manufacturing systems. DIGSAU’s recent works include the Construction Training & Education Center in Wilmington, Delaware; the University of Delaware Campus Bookstore in Newark, Delaware; and, the Sister Cities Park & Pavilion in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. On the occasion of their Emerging Voices lecture (video below), the following interview was conducted through a series of email conversations between League Program Associate Ian Veidenheimer and the partners of DIGSAU.

Ian Veidenheimer: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practice in today’s economic, professional, and intellectual climate?

Mark Sanderson: The economic challenges of starting an architecture office were amplified by the recession, but it wasn’t all bad—it taught us to be both careful and better at taking risks.

Professionally it is easier to adapt to a changing world when nobody knows who you are and you don’t have 50 employees. There are great opportunities today if you are willing to practice architecture differently.

Jules Dingle: In terms of the intellectual climate, it’s refreshing to get beyond the ideological battles that were taking place when we were in school. As a profession we seem to be more tolerant of different points of view. If somebody wants to build peripteral temples then I say go for it—I just hope that they do it well. There is a heightened interest in making things these days, and the people who love what they make historically have made some pretty great things. Our focus is simply on making things that elevate human experience.

Sister Cities Park & Pavilion, Philadelphia, credit: Todd Mason/Halkin Photography | click for a project slideshow

IV: This lecture and prize series specifically emphasizes “voice.” How would you describe your voice, particularly since you all came out of the same office, Kieran Timberlake?

JD: We certainly don’t speak with just one voice. I guess you could say our voice is polyphonic. As a collaborative office of 14 people, we can make a pretty wide range of sounds.

Jeff Goldstein: We are also interested in engaging and assimilating the ideas and priorities of our clients who offer a unique voice to each project.

IV: DIGSAU seems to make work for itself. How does this proactive approach influence the development of your work? I’m thinking of the Corn Mobile compared to the University of Delaware Campus Center.

JG: We had several goals when starting DIGSAU. Working hard and having fun doing what we enjoy was one of them. We also found out quickly that few people are willing to risk hiring a young firm that hasn’t built anything yet.

Our focus is simply on making things that elevate human experience.

James Unkefer: The Corn Mobile was a creative and collaborative folly that taught us something about ourselves, and how to engage in a design and fabrication process with people coming from completely different perspectives. Our competition entry was probably a bit too precious for the concept, but the impossible schedule and a $300 fabrication budget forced an improvised collaboration with an eclectic team that included a metal worker, a carpenter, a font designer, several construction trainees, and a crew of farmers who were just crazy enough to spend a few days with us converting a late ‘80s Ford Bronco into a creepy black convertible filled with dirt and several hundred transplanted stalks of corn. The process beat some of our fussy architect tendencies out of us and gave the project some teeth.

MS: The UD Bookstore project came out of an RFP response that challenged the internal, anti-urban big-box store described in the project brief. Like the Corn Mobile, that project was optimistically critical of the status quo.

JU: Yes, but there was a very specific set of programmatic goals that had to be addressed. At the end of the day, the Corn Mobile taught us more about ourselves, but both had productive outcomes.

IV: You work through consensus. How does the structure of your firm—particularly the relationship among you four principals—allow for this approach?

JG: For us consensus is as much about trust and respect as it is about agreement. It is a process that requires a commitment by all involved to work together towards the best possible solution to a given problem.

JD: We also emphasize that consensus is very different than compromise. We actively debate potential solutions for each design problem until we feel the best solution has risen to the top. After a direction is established we all get on board and work to strengthen the design. At least until the next crit…

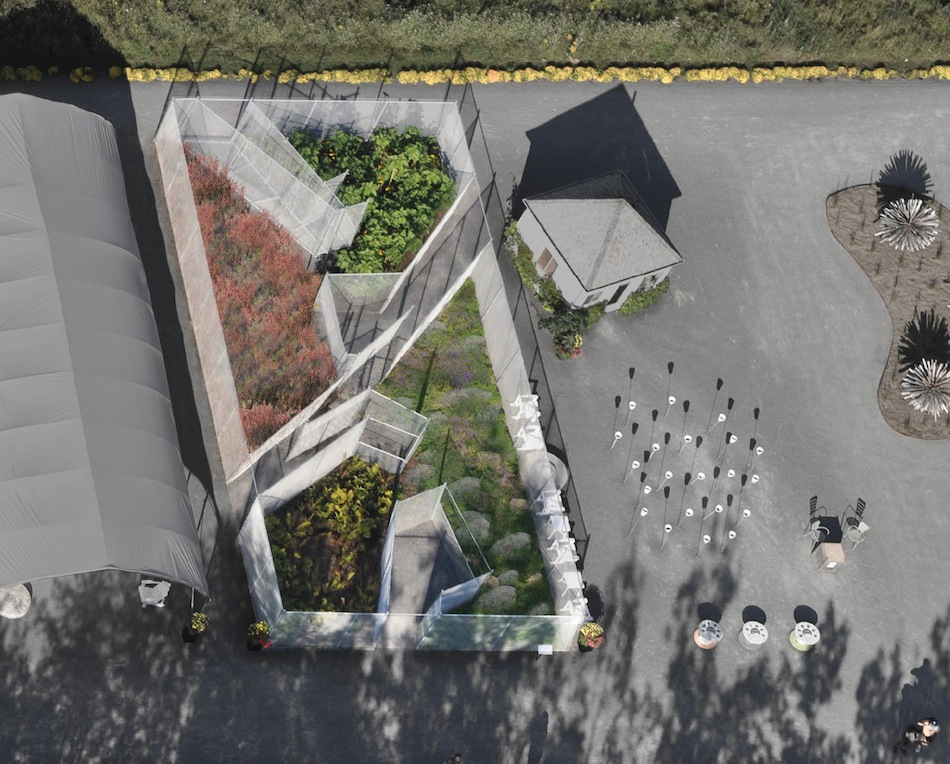

Dogfish Head Brewery, Milton, Delaware, credit: Pixelcraft

IV: Much of your work is in the Mid-Atlantic and your practice is based in Philadelphia. Is there a regional approach or set of conditions that is specific to that area?

JG: I’m not sure, but maybe Philly’s strength is that a lot of people are doing work that is accessible and that doesn’t take itself overly seriously. We are interested in responding to the context of a given project on a specific level but rarely do we think about that response in regional terms.

IV: Texture is prominent in your work. What is the value of textures—their production, look, and effect—in architecture? How does texture relate to craft, vernacular, and nostalgia?

JU: We are interested in texture as a means to convey different ideas about craft, materials, light, and scale. In different ways, we want our work to be as expressive of these characteristics as possible.

MS: Vernacular architecture has such a rich tradition of the handmade, which is often evident in the texture of the buildings. Contemporary materials and construction techniques offer less opportunity for that and there is a much greater emphasis on the joint between materials. We spend a lot of time looking for materials or construction techniques that have a strong materiality.

JG: Past generations sought to conceal the process of making something in favor of machine-like precision. We spend time with the builders and tradespeople to learn about how we can capture their hand and their process in the finished product.

IV: How do high- and low-tech interact in your work? Where is chance in this equation?

JU: We’ve acknowledged that no matter how you may try you can’t have complete control over a design and construction project, and that’s okay—in fact it’s a good thing. Chance can be a useful design tool.

JD: Projects like the Agrarian Artist Studios outlined a set of construction guidelines that determined the resulting forms of the structures in general, but relied on chance in detail. Mounding earth as concrete formwork and excavating the house with a shovel is pretty low tech, but the concrete mix design, the carbon fiber reinforcement, and the engineered formwork guidelines for loosely defined complex curves were reasonably sophisticated. We are more interested in unlikely combinations and juxtapositions of building technology than in operating on the strictly futuristic or primitive fringe.

IV: Many of your materials are re-used. What is your attitude toward reclaimed materials?

JG: Construction, no matter how well intentioned, is a burden on our environment. Re-use of structures, components of structures, and materials just makes good sense. The exterior cladding on the Rural Loft was salvaged from a collapsing barn on a neighboring property. That solution was as much about finding an economical siding material as it was about environmental stewardship or an aesthetic agenda. One building was falling apart and becoming a burden so we used pieces of it to make something new. The Romans did that kind of stuff all the time.

MS: Also, re-using something in a different form plays to our creative and resourceful instincts as problem solvers. We like the fact that reclaimed materials often have a story, reflected in a unique patina or tactile quality that invites people to touch.

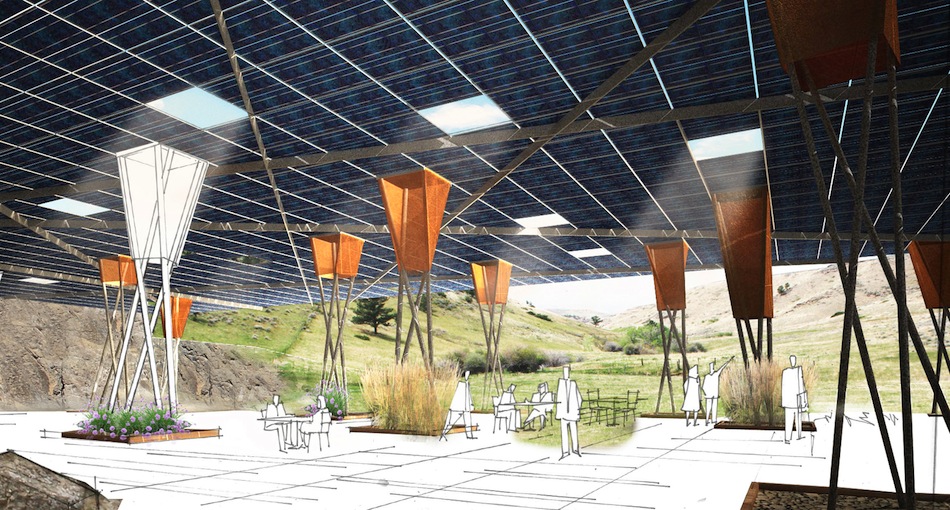

Construction Training and Education Center, Wilmington, Delaware, Projected Completion 2013, credit: DIGSAU

IV: How does your office think of labor as a part of architecture?

JU: Many of our ideas come from understanding the workforce and resources of a project. We seek out dialogue with craftspeople whenever we can. Humans can make almost anything, and you can learn a lot from them. Robots are pretty good at making things too—we work with them as well—they just aren’t great teachers.

MS: We really value the experience of working with the people who actually are making the building as it affords the opportunity to expand our thinking. At the Construction Training and Education Center, our clients didn’t have much money but they did have plenty of salvaged materials and an endless supply of low-skilled to no-skilled laborers to build the building. In that project we designed a construction methodology that relied on simple repetitive carpentry tasks. For example, the process of fabricating rain screen panels introduced trainees to basic woodworking and layout techniques while allowing them some freedom to compose each panel. Like squares in a giant quilt, the imperfections of individual panels give way to the larger field of panels. We wouldn’t have designed that wall for any other client. The process was the idea and it was born out of its circumstances.

IV: You are beginning to propose large projects at the urban level. How do scale, proportion, and what you call “things that are simple, hacked, and broken” play into this work?

JD: Much of what surrounds us in the city is broken, but those things can still be quite beautiful. Simple ideas sometimes have the potency to reveal that beauty whereas scale and proportion are intuitive tools for distilling simplicity from complexity.

JU: We don’t start a project with the idea of designing something that is broken, but we do recognize the inertia that is working against the goal of perfection. Ideally, we manage to use that inertia in our favor rather than fighting against it and learn something along the way.

•••

DIGSAU, Emerging Voices 2013, complete lecture video | Recorded March 21, 2013 | Running time: 52:13

•••

Jules Dingle received a M.Arch from the University of California, Berkeley, and has taught at Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania. Jeff Goldstein received a M.Arch from Yale University and currently teaches at Temple University. Mark Sanderson received a M.Arch from the University of Pennsylvania and has taught at Temple University. James Unkefer received a M.Arch from Yale University and has taught at the University of Pennsylvania. The office is the recipient of numerous AIA Pennsylvania Chapter Merit and Honor awards. See more of their work at digsau.com.