Density diversified: Three housing types for Ravenswood, Queens

For the Making Room design study, Gans Studio designed housing for the individual resident and the larger urban context simultaneously.

In order to provide housing responsive to the way New Yorkers live now, it makes sense to assess needs at the scale of a neighborhood. In this way, we design for the individual resident and the larger urban context simultaneously. The new typologies can be leveraged to benefit a neighborhood’s physical and social fabric. For this study, we chose a neighborhood with both internal desire for housing and also external pressure for development. These two dynamics often represent different economic user groups, the perhaps too-simply labeled gentrifiers and the stalwart local. In the context of a neighborhood, new typologies can potentially create an unprecedented mix of these populations and thereby satisfy both population pressures.

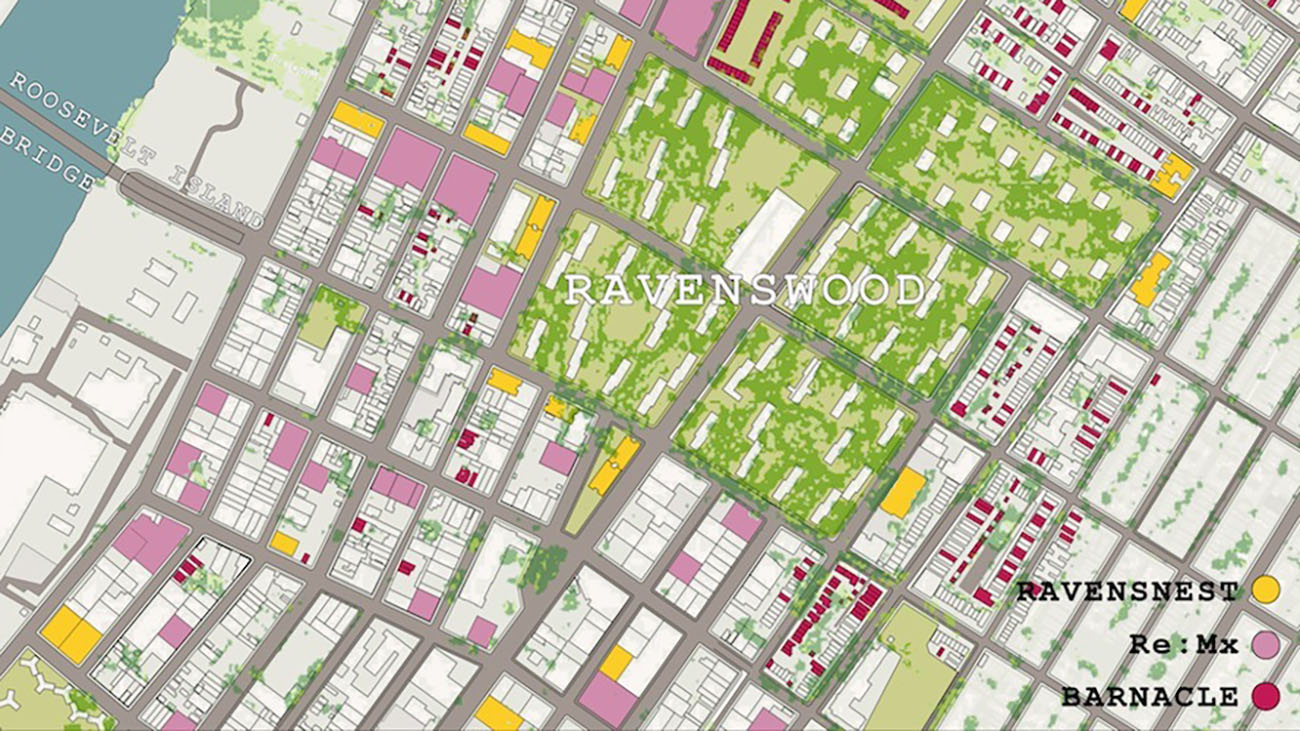

Our study neighborhood, Ravenswood of Astoria, Queens, has a characteristic structure, found repeatedly across boroughs, namely an upland middle-income residential fabric that abuts a low-lying landscape of public housing adjacent to an underutilized manufacturing zone on an increasingly re-developed waterfront.

In the case of Ravenswood, the upland fabric is largely detached and semi-detached residences; the lowland towers-in-the park were developed by both the New York City Housing Authority and Mitchell-Lama and so, respectively, house low-income and middle income residents. At the river’s edge, the manufacturing waterfront extends south to Long Island City and to the recent high-rise residential development that is on the march toward Astoria.

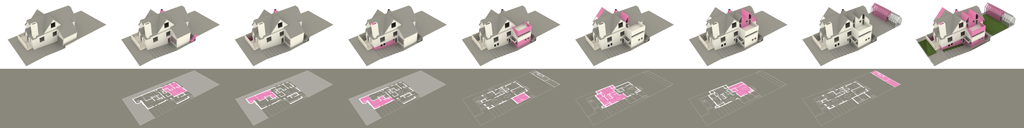

The Barnacle Block

We made three design proposals, one for each of the neighborhood sub-contexts:

The Barnacle retrofits a typical upland, owner-occupied, Tudor-style house with seven additional dwelling units (ADUs), each with its own entrance but none that competes with the primary place of the homeowner. It is an opportunity to increase density without radically altering context or zoning. A mews that is also a social space handles the increased parking and garbage demands generated by the plan. Renters might include: an extended family, the local next-generation, new arrivals, or care-givers.

The Ravensnest

At The Ravensnest, groupings of two floors are organized around double-story balconied courts with very large units on the lower level and small apartments above. This mix accommodates the multi-generational and extended families particularly found in the NYCHA Ravenswood Houses, which is currently filled to capacity with a long waiting list. The buildings are located not on the Ravenswood grounds, but directly across from them in order to create a more robust frame for the landscape within, which will most surely become an increasingly valuable resource as the city becomes denser. The ground floor has dry-proof commercial space that serves the neighborhood at large, and so begins to blur populations within its urban edge.

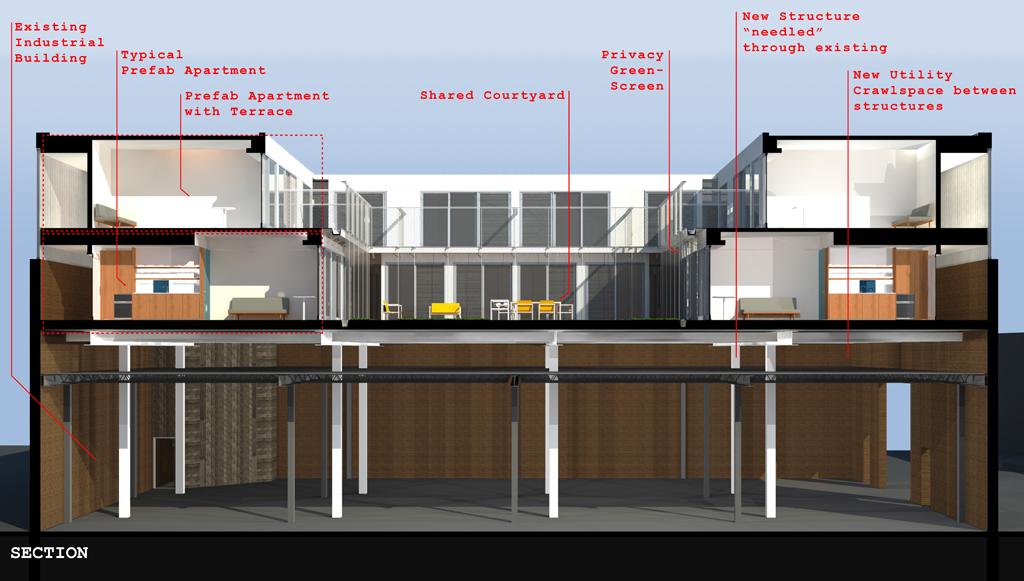

Re:Mx

Re:Mx proposes that pre-fabricated micro-units be installed above the floodplain, on top of an existing manufacturing base in a way that meets the desire of industry and of local institutions like The Noguchi Museum to simultaneously preserve and develop the fabric. The price point of a micro-unit in this location makes the type a potential social mixer for the struggling artist and employed young adult from Ravenswood alike. The upper units are ADA-accessible despite their size. Social space expands and completes the apartments. Besides the main courtyard that provides required light and air to all the units, there are corner dining and laundry lounges.

Re:Mx