What Does a Building Sound Like?

Deborah Garcia of DEBORA.STUDIO tunes into architectural systems and structures, from AC ducts to library courtyards.

August 4, 2025

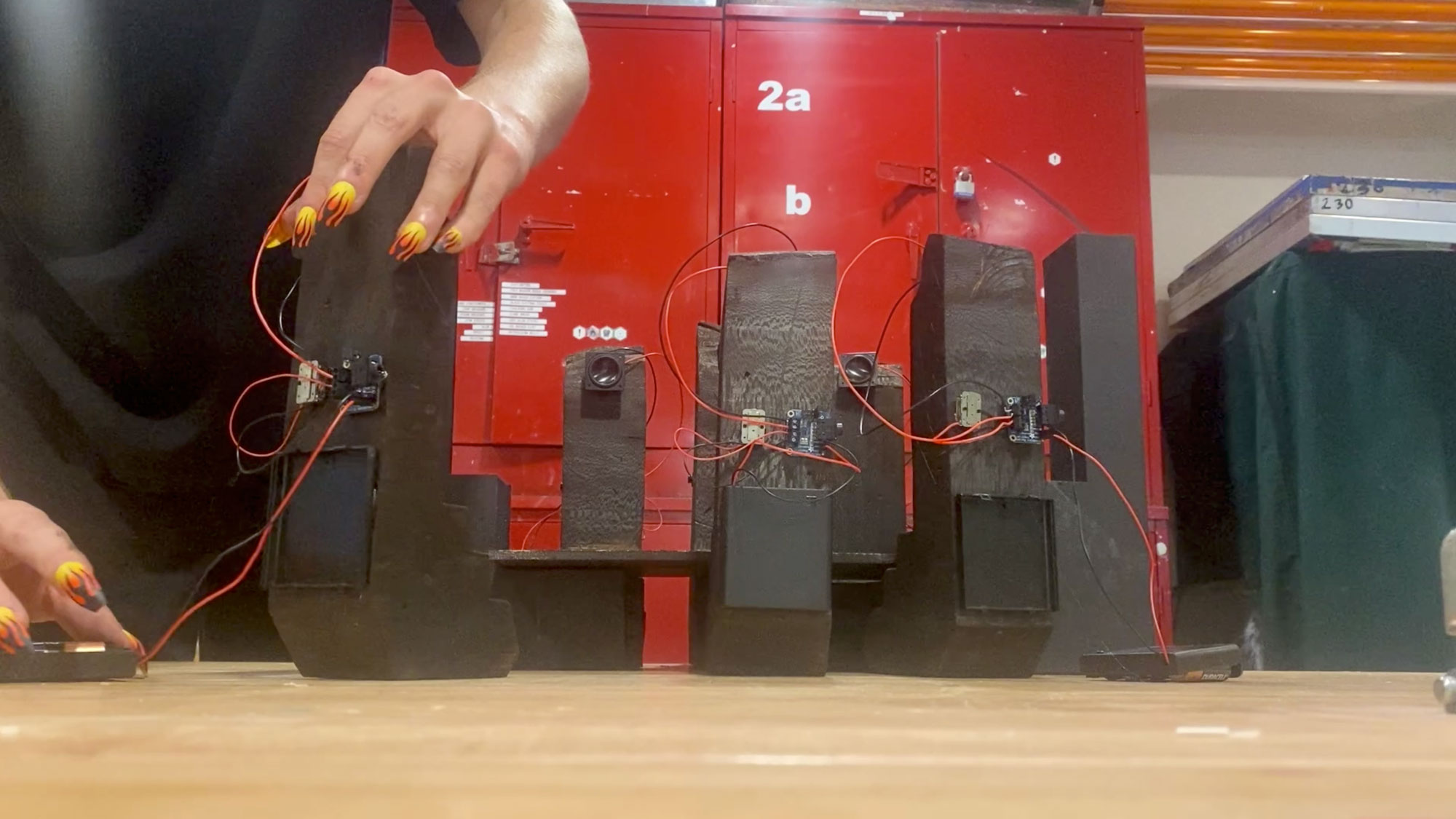

DEBORA.STUDIO | RECORDAR (Study Models for a Loudspeaking Architecture, [sound testing sonic model]), MIT Architecture, Cambridge, MA, 2022. Image courtesy DEBORA.STUDIO

Deborah Garcia of DEBORA.STUDIO is a 2025 League Prize winners.

Deborah Garcia is an architectural designer and researcher whose work focuses on reimagining everyday structures through multisensory activation. Her recent research developed strategies for using sound as an architectural medium and historical record. For the 2025 League Prize exhibition, Garcia created a composition of extracts taken from her work in designing and producing architectural sound systems, highlighting the ever-present sonic noise of the built environment.

Urban Omnibus Managing Editor Kevin Ritter-Jung spoke with Garcia about her journey to the intersection of sound and architecture and how it feels to experience the designer’s multisensory activations.

*

Kevin Ritter-Jung: Your League Prize lecture was titled “Doing It for the Plot.” How do you think about the word plot in relation to your wide body of work?

Deborah Garcia: It felt fitting as a word to riff off of. So much of my experience in doing projects—which I don’t think is dissimilar from a lot of young designers—is finding opportunities, which often takes the form of scheming up ways of making things happen. In some ways, our landscape of opportunity feels quite limited, and you really have to find opportunities to enact design or turn a lack into a possibility of something. So in some ways, plotting felt like a word that describes what I do constantly and already in my practice at large. And I think that “doing it for the plot” hint[s] at jumping into what feels like a place where there’s work to be done and not really having a solution just yet. It’s a way of working that is attuned to opportunities for change. And that attunement leads to exciting things, but doesn’t lead to a lot of clear step by step processes.

Ritter-Jung: You’re working with this set of sonic tools that feel quite novel within architecture, and I’m curious how you developed this skillset in sound and how you made your way to this intersection of sound and architecture?

Garcia: I think a lot of it has to do with the way I grew up. Sound has always been very present. I’m from Los Angeles, a very big car-culture city, and sound is very much tied to cars, as well as [the] impromptu use of space. My fondest and earliest memories tied to sound systems [are] church and family backyard quinceanera transformations where sound systems [are] just unloaded out of the back of a car and then you’re ready to go.

So there’s that personal history, but [my interest] really started when I started to do more video-oriented research. One of my early explorations was when I spent a summer in Nebraska working on a corn farm, right around the first Trump election, doing research about Middle America and infrastructure. I would take hours of video and remixed these hours and hours of flat road infrastructure documentation into a clipped rhythm sequence. I started to use video as a way to understand the rhythm of the road and rhythm of landscape. That was the first time I thought about what you can capture through sonic experience.

My time at MIT was really formative. The three years that I spent there led to so many conversations with artists and designers in their Media Lab and people that do electronics work, like sound artist Cristóbal García Belmont. MIT was a major shift that put some tools in my back pocket to [understand] integrating sound as a design component, rather than something that gets attached at the end or momentarily fills the architecture.

DEBORA.STUDIO, Joseph Zeal-Henry | SUPA Soundsystem, Harvard ArtLab, Cambridge, MA, 2024. Image credit: Malakhai Pearson

Ritter-Jung: These installations speak to sound as a spatial element, the ways sounds fill rooms and landscapes. Could you speak to the relationship between sound and the built environment?

Garcia: This [relationship], for me, oscillates between two paths. There are projects that are about the structure of the sound system, and the sound is less choreographed or curated. [These projects] have much more to do with an event. The Harvard ArtLab project [SUPA SYSTEM, with Joseph Zeal-Henry] was about the system architecture, and the sound works within a matrix of organization that can open or close.

In other projects, I’m thinking about how much architecture is already sonically active. For example, right now I’m looking at your screen and there’s an AC duct poking out of the ceiling behind you. We don’t often think of these systems that are so embedded within the “architectural body” as sonically charged, but they are. Ventilation is a very simple system, and these things are really loud. There are constant sonic patterns and rhythms in our lives that we usually don’t listen to. That’s a thread that’s been growing in my interests and where I would love to play more: recording building systems, specifically ventilation, and playing with ventilation amplification or modulation.

Ritter-Jung: RESPONDER, an installation at the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library in Columbus, Indiana, that recorded and amplified the sounds of the building’s internal systems, seems to be in the vein of the second track. Libraries are often branded as quiet spaces, but your work draws out a space that is more sonically alive than we may first think. When you first went to that space, what did you notice as you started listening, and what made its way into the final piece?

Garcia: That was a really amazing site for a sound project. One, it was suggested to me. The Exhibit Columbus team is amazing; they’re so aware of their city. When I got there, I was trying to think about different places where a sound project like this could intervene. My first immediate connection in Columbus was to the tall Eero Saarinen tower, which is right across from the library, because I saw the tower as a kind of clone of a sound tower and [thought] maybe they could talk to each other. But someone suggested I go across the street and check out this sunken space [in the courtyard of the library, designed by I.M. Pei]. The minute I walked down those stairs, [I noticed] the way that sound shifts in that sunken courtyard, [which] is just absolutely wild. It cuts out so much of the street sound, but then it bounces sound in specific ways that are so interesting. [The space] already operates like an instrument.

The other interesting thing is that [the courtyard] is at the entrance to the Children’s Library. So unlike the other entrance, which is very quiet, the Children’s Library is the back door of the building. Doors are opening and closing; kids are screaming; there’s no sense of decorum. The traditional library vibe is already being disrupted. I spent some time thinking about how to tune something that sounds like a sonic performance, with a story that you needed to digest. But I was much more interested in [creating] a moment of intrigue, the way that cicada sounds are so wild in Columbus in the summer. It’s something that maybe you spend some time with, and maybe it triggers a curiosity or moment of listening, but [is] not hyper-choreographed.

DEBORA.STUDIO | RESPONDER, Sonic Activation at Cleo Rogers Memorial Library, Exhibit Columbus, Columbus, IN, 2023. Image credit: Brooke Holm

Ritter-Jung: Rayshad Dorsey said in his introduction to your lecture that your work needs to be felt to be fully understood. We can see your projects in this online exhibition, we can kind of hear them through our laptop speakers or headphones, but what is the bodily experience of sharing space with these structures?

Garcia: These projects are so site specific and event specific. With the Exhibit Columbus project, you could go up to it and listen and touch it and feel its vibration. I have no interest in high fidelity or hyper-engineered sound systems that are built for clarity. So much of sound system culture is about perfect attunement for maximal sonic experience. I think that largely has to do with deeply embedded questions of sound purity. I’m less interested in that and much more interested in the presence of sound objects and the way that our bodies can experience them.

RECORDAR [a nine-foot-tall tower which contains a multi-channel recording and broadcasting sound system] is built in a way that when it makes enough deep tones, you can feel them; the system will creak and groan and shake. There are different speakers built in that send sound through the material versus moving air. So those are really activated when you sit on the structure, or when you’re near it. You can really feel it in the ground. So they don’t operate like a traditional sound system. The engineers that I worked with often looked at [RECORDAR] and were like, this leaks. And I was like, yes, it does. But the question of how to translate that into a digital experience, that’s something yet to be discovered. Right now, I think it largely exists in the moment when you can experience it, and then the documentation version is capturing what you can of that experience.

DEBORA.STUDIO | RECORDAR (Study Models for a Loudspeaking Architecture), MIT Architecture, Cambridge, MA, 2022. Image credit: Brooke Holm

Ritter-Jung: Do you have a favorite and/or a least favorite sound?

Garcia: Ooh, that’s such a good question. I’ve been obsessed with the steam system in New York [City] for a long time. In New York, the steam system leads to a lot of moments of leaking, where you see the city exhausting all around you. One of my favorite sounds is when a fan malfunctions in the subway and there’s a repetitive techno sound. It almost feels like there’s a rave, which I love. But at the same time, a big phobia of mine is that we’re going to get stuck in the subway in a heat wave. The sound of malfunction can be both really, really beautiful and sound like music, and at the same time a harbinger of failure.

Ritter-Jung: Leaks and slippage have come up a lot in this conversation.

Garcia: I’ve spent so much time looking at New York City from Governors Island [the location of the Institute of Public Architecture, where Garcia is the residency director]. I’m looking at these massive modern buildings in the Financial District which are—in so much of their engineering and architectural language—based on the concept of the machine that will operate perfectly, but so much of the city is systems not working.

We’re in a moment where, especially with climate change, these systems are being tested by environmental realities. And buildings that have been built to be engineering marvels are failing. For me, the leaks and the slippages are actually moments of breath, a moment where a crack opens toward some air in the middle of this hermetically finessed and engineered architecture. And so there’s something about thermal joy and thermal panic that intertwines, for me, with sound. It goes back to the very beginning [of our conversation] about plot. To me, moments of breaking suggest opportunity, but that can be an emotional roller coaster as well.

Interview has been edited and condensed.