Courtroom spectacular

Founded by a designer, the Young New Yorkers program uses art and architecture to rethink young people's experience of the criminal justice system.

Rachel Barnard of Young New Yorkers is a 2019 League Prize winner.

How can architects and artists make a meaningful difference when it comes to problems like mass incarceration and institutional racism? For Rachel Barnard, an Australian designer who moved to New York to study at Columbia GSAPP, one answer is to teach the people most affected by these issues how spatial and aesthetic tools can help them engage productively with broken systems.

Barnard spoke with the League’s Catarina Flaksman and Sarah Wesseler.

*

Catarina Flaksman: Can you talk about the founding of Young New Yorkers?

Rachel Barnard: It began when I was awarded the Goodman Fellowship from Columbia GSAPP—it’s a $20,000 prize for a graduating student. My proposal for the prize was for a public art project that provided a platform for 16- and 17-year-olds who were prosecuted as adults to talk back to the system, given that they were too young to vote.

Flaksman: How did this idea come about? Did you have experience working with the criminal justice system before you created the proposal?

Barnard: I had never worked in the criminal legal system, but I was very interested in who gets to use public space—whose voices get heard and why—and these questions very much applied to teenagers being prosecuted as adults in the public space of a courtroom.

The program started with the idea that young people would spatialize their experiences with—and visions for—the criminal legal system in an immersive project, offering their lived wisdom to the criminal legal professionals working in the system that was prosecuting them.

I started a working group of about 10 people, including social workers, lawyers, artists, and members of communities that are heavily impacted by the criminal legal system. We would meet every two or three weeks.

Early on, the public defenders in the working group thought that if the young people were going to create a public art project as part of the program, it could possibly be court mandated. At one point, two of the public defenders ushered me into a courtroom to talk to a judge, Judge Gubbay, as he set up his bench for the day. He agreed to the court mandate idea, and about eight weeks later, after securing buy-in from other agencies, we had our program. It became the first arts-based alternative to incarceration for teenagers in the adult courts in Brooklyn.

The first program lasted 8 weeks and culminated in an exhibition in the courtroom that the young people produced. The prosecutors, judges, and the defense attorneys were so moved by that exhibition that they asked me to keep going.

That first exhibition was very simple. It was inspired by a public art proposal that one of the participants made based on his concern that people in his neighborhood didn’t remember to have goals and dreams. He proposed that hundreds of people could go to the Brooklyn Bridge and write down their dreams for the coming year on paper airplanes that would fly off at the same time to create a spectacle and a collective memory.

For the exhibition, we translated that vision into everyone writing down their dreams on paper airplanes. At the end of the evening, on the count of three, judges, prosecutors, and defense attorneys, along with the young people they’d sentenced to the program, all flew their paper airplanes into the air.

That’s when I realized that this immersive, interactive spatial experience provides a new way for young people and courtroom professionals to interact, and that it has the potential to reconfigure how young people are engaged in the courtroom—not just collapsed into their rap sheet, but as full individuals with tremendous amounts of potential.

Kimani (right), a graduate of a voluntary Young New Yorkers program, speaks with Judge Joseph Gubbay at a March 2019 exhibition. Credit: Mansura Khanam

It could humanize the culture of the courtroom and lead to better sentencing practices that are developmentally appropriate.

Flaksman: You trained as an architect. How do you view the role of architecture in this program?

Barnard: We don’t design buildings, but we design an installation that spatializes the young people’s experience with the criminal legal system and allows them to reimagine it.

During the program, we talk about the existing structures of the courtroom: the judges at the bench, the juries to the side, a witness box in front of the judge, your defense attorney beside you, and then the prosecutor, a rail, and the people waiting behind the rail. We reconfigure the space so those spatial hierarchies are not so present in the room.

In the most recent program, many of the young people had mental health challenges, so they chose to center the exhibition around self-care and an exploration of what it takes to truly thrive. They turned the witness box into a “declaration of blossoming,” where the young people would invite the criminal legal professionals to proclaim in a very playful, whimsical way that they would make a lifetime commitment to prioritize their self-care.

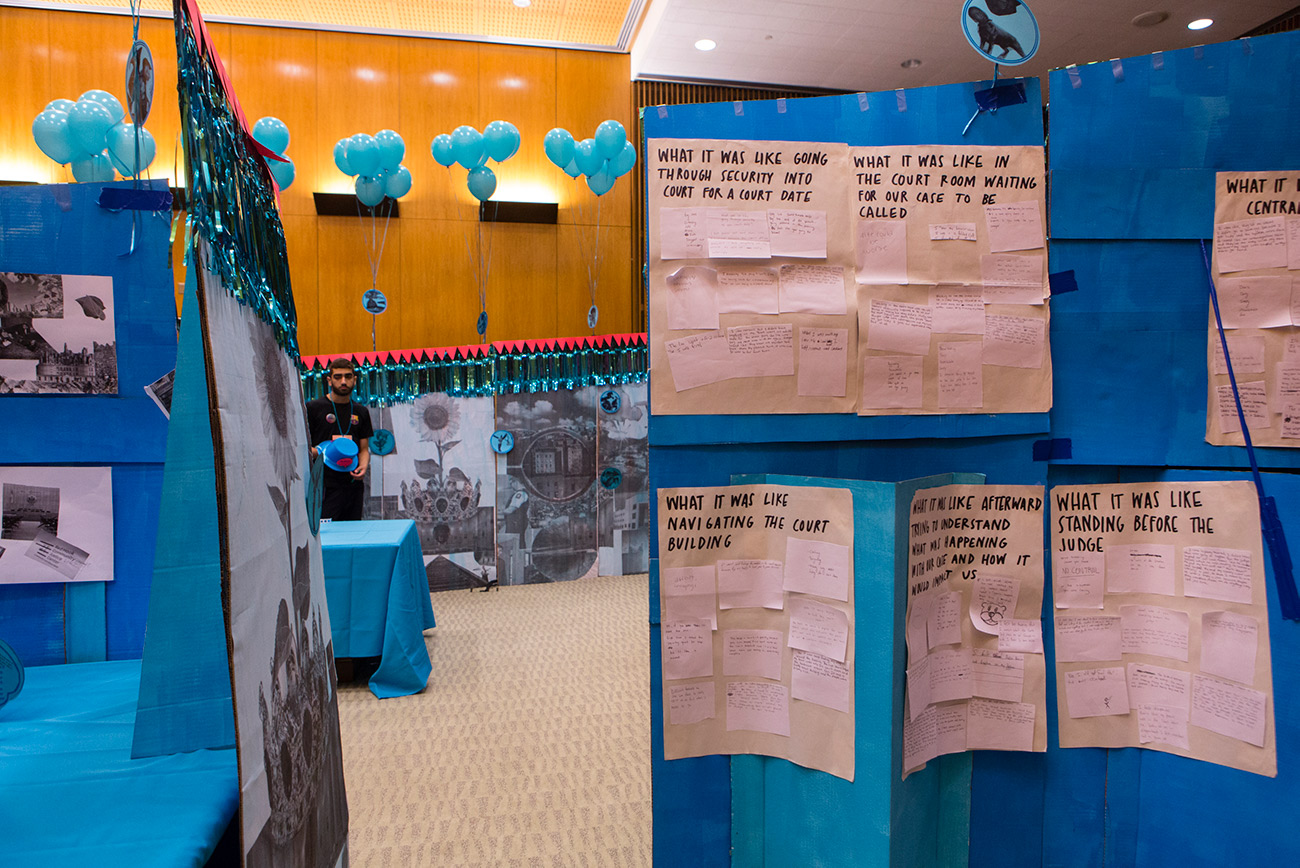

We take the existing courtroom structures and we playfully convert them, with the use of balloons, flowers, color, or ribbons, to give wildly different aesthetic cues as to what’s possible within that space. Moving through a courtroom is scary; it can be overwhelming. But everyone knows how to be at a party. So when you come in and the social cues are like those of a child’s birthday party or a picnic, it creates new opportunities for social engagement within a system that is normally oriented around hierarchy, separation, and judgement.

Sarah Wesseler: How does the idea of rethinking the courtroom space resonate with the teenagers? Do they get into it right away, or does it take time for them to understand the relevance to their personal experiences with the legal system?

Barnard: Sometimes they’re like, “No, no, they’re never going to let us do that.” Even after seeing photos of past exhibitions, it takes a while for them to realize that they can do it. But when we take it on, they step up and become the most fantastic visionaries, hosts, and leaders in the immersive installations.

They understand that some spaces are designed to be dehumanizing. Early on in the program, we talk about dehumanizing spatial experiences. For example, the handcuff as a spatial device that means that we are not free to use our bodies—how did that make us feel? What did we make that mean about ourselves in the world? When you’re in the back of a police car, what could or couldn’t you do? Getting your thumbprint taken and knowing it was going to be inside of the system for the rest of your life, what was it like? What was it like in central booking in the cell where you were held for up to 36 hours with a group of strangers waiting for your first court appearance?

We go over all that to understand what was happening externally during this period so we don’t internalize it so much, so that the trauma doesn’t become a secret object inside of us, and that the next time we are stopped by a police officer—which is very likely to happen in some neighborhoods—that hidden trauma doesn’t become a trigger for an automatic reaction. We aim to own our stories, and to rewrite them.

Wesseler: Can you talk about some of the ways the kids thought about transforming a courtroom, and how they made it happen?

Barnard: One group was really interested in brain science. We were going over the science around neurological development, and how the frontal lobe cortex isn’t fully developed until about 25 years old. Until then, biologically, we’re wired to be more impulsive and oriented towards immediate rewards.

As a society, we know that we have high levels of policing in many of our neighborhoods, and that if you get a criminal record at 16 or 17 it will last for the rest of your life, and that can impact your ability to gain employment, social services, housing, education. We also know that at 25, if someone has enough opportunities, they are far less likely to be arrested.

The young people couldn’t believe that this was known science and yet they were still being held accountable as adults. So they created this exhibition called Courtroom Spectacular, with a quiz on entry that broke down that science. They asked the criminal legal representatives things like: How old are you when you’re prosecuted as an adult in New York State? What are the impacts of a criminal record? How old are you when you develop consequential thinking? And then there were medallions for each guest with an image of a brain that told everyone whether you had a senior brain, an adult brain, or an adolescent brain. Everyone had to go around with their brain development hanging from their necks.

The young people also put up their written experiences of each spatial stage—central bookings, waiting for the judge, moving through courtroom and security—and they all read them out loud. It was one of the most impactful parts of that exhibition, because when you’re going to court every day as a professional, you forget what it’s like for someone doing it for the first time when the possibilities for their life are on the line.

Also, because more than half of the young people wanted to be tattoo artists, they turned the judge’s bench area into a tattoo parlor. The visitors would sit one-on-one with a young person, describe their vision for justice and for their own life, and the young person would offer them a word of affirmation by using eyeliners to tattoo their body or their hand. They would write “leader” or “unstoppable” on the criminal legal people, then put sparkly gemstones around it, or whatever design they wanted.

Another group got really into Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Sometimes we use Maslow’s hierarchy in our classes to talk about what need the participants were trying to meet when they made the choice that got them arrested. They talk about times when they didn’t know where they were going to stay at night, or times when they knew they were unsafe at home, or days when they’d gone hungry. And we talk about how when we are worried about those things it’s hard to make long-term choices, because we’re in survival mode.

The young people came up with the idea to have a series of obelisks in the exhibition where visitors would answer questions like, have you ever not known where your next meal would come from? Have you ever felt like the police weren’t here to protect you? Visitors would place stickers underneath the question to indicate yes, no, or in the middle. So the exhibition started to document where everybody’s needs were using an architectural spatial device that was playful, but that revealed things that are normally hidden.

Flaksman: Do the young people choose which subjects to focus on for the exhibitions themselves? How does that work?

Barnard: Yes. In the classes, we look at how the criminal legal system works, how we can navigate it, what the different parts of our court experience and our mandate mean, and how we can be responsible about that. We look at the trauma of criminal involvement. And then we look more deeply at the system itself, and opportunities for leadership for ourselves.

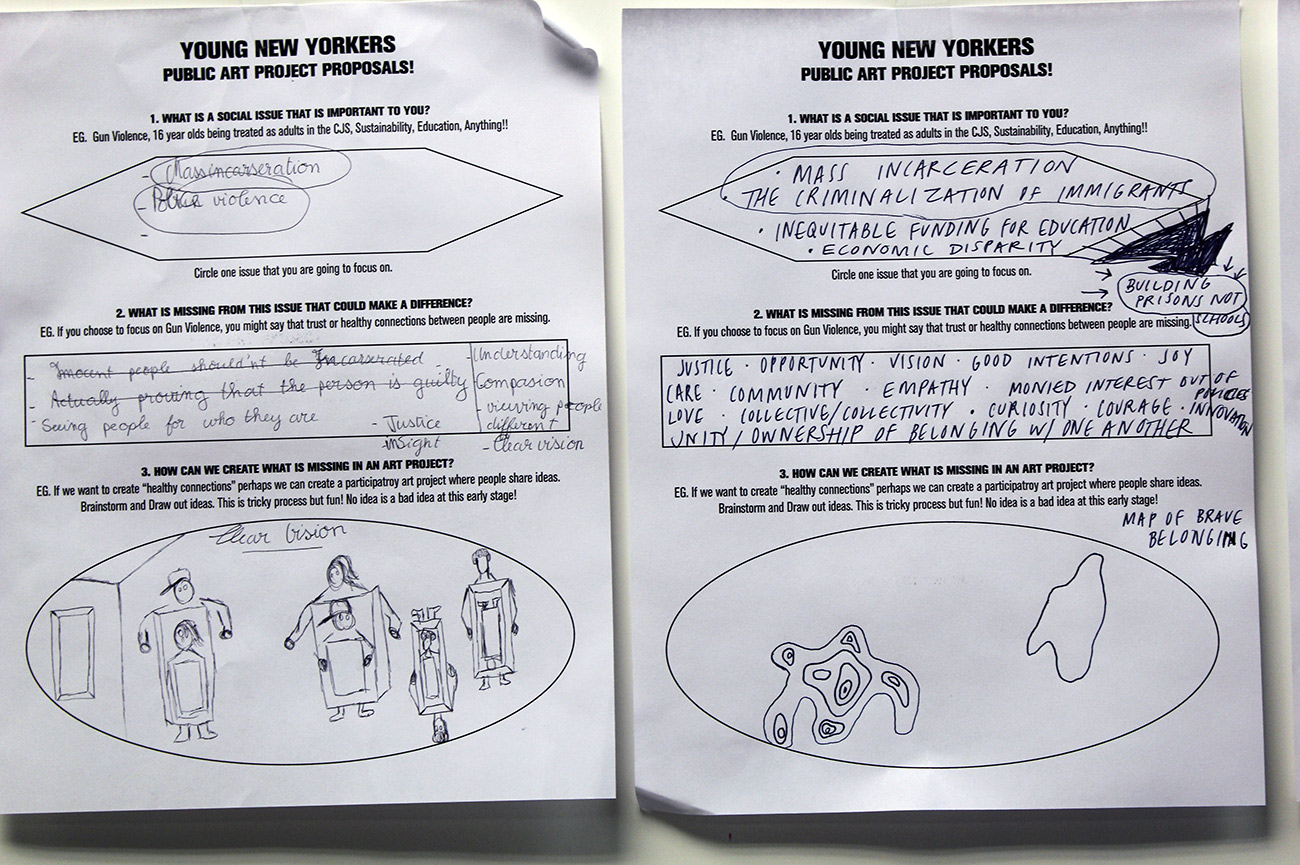

We start with a simple worksheet to brainstorm the different areas of the criminal legal system, or different social issues, that we would like to see transformed. Then we circle which one is most important to us and that we would really like to work on. The young people do this individually at first, and then we write down not what’s wrong, but what is missing. If it is, let’s say, 16- and 17-year-olds being prosecuted as adults, they might say that compassion, trust, understanding, acknowledgement of brain development are missing. And then we go, “Well, what crazy project could we come up with to create an experience where understanding and acknowledgment and so on are present?”

We then come back as a group and focus on one social justice issue together, bringing multiple elements from those proposals into one project.

Sometimes they come up with the most brilliant ideas. For example, one group that was really concerned with police brutality imagined that every month a police officer would have to spend one day in a pink uniform. When you’re wearing that uniform, it meant you’re catching good things people do. You might stand at a stop sign and count the hundredth person to stop, then give them a voucher for a coffee or an appliance store. They called it Catching Kindness and created this game inside the Department of Probation, where they would give people the opportunity to be kind and generous, then reward them accordingly. The officers loved it.

Flaksman: New York recently changed its laws so that people under 18 won’t be prosecuted as adults. How will this affect the program?

Barnard: We now accept people up to the age of 25, which is when the part of the brain that governs consequential thinking is fully developed. We’re committed to partnering with the criminal legal system so that young people avoid incurring a lifelong criminal record during this adolescence period.

Having said that, once this change went into effect, we started to also accept referrals from family court. We currently accept up to five young people per week from the Brooklyn and Manhattan Family Courts. In the future, we may also have special programs for family court for people between 15 and 17.

Flaksman: How do the criminal justice professionals react to the exhibitions and to the transformation of the institutional space they’re used to?

Barnard: They love it. They work in an environment with high levels of secondary trauma. They can get so ground down and depressed by what they’re witnessing that they can begin to resent the people they intended to serve. These exhibitions create celebratory spaces where people can connect with each other in healthy and joyful ways, and it’s great for criminal legal professionals.

They want to see positive outcomes. They want to celebrate. It opens up a space where they can feel that more things are possible than just the default churn of the criminal legal system.

If criminal legal staff are honored and supported, they’re able to make more just choices. Rather than blaming professionals as a community, we need to redesign the system so that everyone can thrive.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

In Conversation: Justice Stephen Breyer and Henry N. Cobb

A conversation centering on the design process of Moakley Courthouse and the civic importance and symbolic power of architecture for the judiciary.

Redefining safety and justice for the twenty-first-century city

Experts discuss the future of justice in New York City in light of plans to close Rikers Island.

Creating an ecosystem for social design in New Orleans

Colloqate helps architects and laypeople alike understand the potential for a more just, equitable built environment.