Arctic architecture

Blouin Orzes architectes has spent decades working to understand the needs of Inuit communities in the Canadian north.

March 18, 2020

The firm's first Nunavik project, a co-op hotel built in the village of Inukjuak in 2000. Credit: Blouin Orzes

Every summer, a container boat leaves Montreal and heads to the remote Canadian north, loaded with construction materials. In its hold: every beam, nail, drywall board, and paint can needed for every building slotted to go up in 14 remote coastal villages of the Nunavik Territory over the next year.

“The departure of the boat at the end of June from Montreal in fact is day one of the season of construction over there. This is really a non-negotiable date. You have to live with it,” said Marc Blouin, who co-directs Montreal firm Blouin Orzes architectes with Catherine Orzes. The short Arctic summer stretches from approximately July to October; once winter sets in, it becomes nearly impossible to transport large quantities of material or work on outdoor building sites. “If you’re late in the process of the bid for material or for contractors, for sure your project will be postponed to the year after.”

Blouin has been working in the Canadian Arctic since 2000, when he was commissioned to design a prototype hotel for Nunavik, the northernmost region of Quebec. The client, La Fédération des coopératives du Nouveau-Québec, is one of several co-ops run by and for the indigenous communities who populate the region, providing critical services like banking, retail, and construction.

The prototype project eventually grew into commissions for hotels and stores in eight villages. The work spanned more than a decade (Orzes joined the team in 2012), enabling the designers to spend time with residents and learn about their needs.

The village of Salluit, Quebec, with Blouin Orzes' co-op hotel on the water's edge. Credit: Blouin Orzes

This kind of exposure is particularly important in a region whose architectural history bears little resemblance to that of southern Canada. Until the 1950s, many Inuit communities were semi-nomadic, building their own dwellings out of snow and animal skins as they moved around in pursuit of game. “The whole context there is really complex in terms of social, cultural, and geographic aspects of the territory. With the Inuit community, it takes a long, long time to really understand their reality,” Blouin said.

Today, community engagement remains a vital aspect of Blouin Orzes’s work. The early phases of projects can stretch on for several years, affording opportunities to explore different options with project stakeholders. “Time is on our side, because life is slower over there,” said Blouin. “It’s different from most of the projects we’re used to in the south, where clients want their project for the next month.”

From gym to concert hall

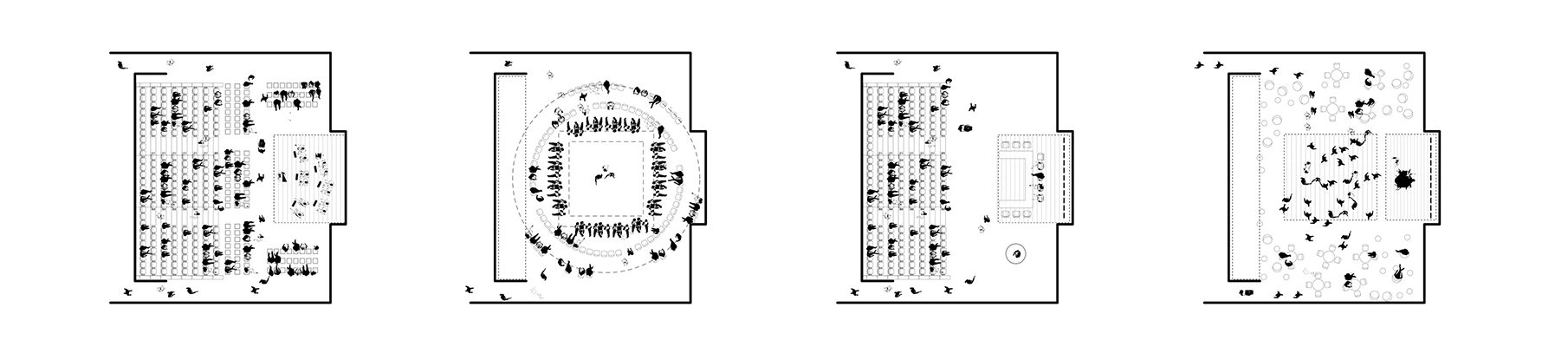

The insights gained from these conversations can sometimes radically change the design. For one project in the village of Kuujjuaraapik, the firm was commissioned to design a community center that could serve as both gymnasium and event space—a common building type in Nunavik. But over time, it became clear that local residents had dreams that would be better served by a different kind of building.

“Slowly, as we got into more specific objectives of the project, talking about theater, about music, throat singing, you realize that you are talking about conservation for this cultural committee in the village—that it was important to have a place with good acoustics, good seating, good lighting,” said Blouin. “It slowly became a more professional concert hall.”

In the finished building, a large, high-ceilinged room provides flexible space for 300 people to gather for concerts, film screenings, banquets, and other events. An elevated platform serves as a control booth for lighting, audio, and projection, while a movable booth provides space for translators—an important resource in a linguistically diverse region. The facility also houses a small community kitchen.

In the harsh Arctic climate, the design also needed to account for conditions like subzero temperatures, strong winds, and varied sunlight, which can range from as little as four hours per day during the winter to more than 20 during the summer. As is typical in the region, the budget was small and construction expensive, particularly due to the need to fly experienced builders from the south and house them for the duration of the construction.

To minimize costs and simplify the building process, Blouin Orzes uses simple volumes throughout its northern projects. At the Kattitavik Cultural Center, brightly colored cladding and bold diagonals enliven a pragmatic, barn-like form. The large, covered front porch and minimal wall openings are representative of the firm’s strong emphasis on transitions between indoors and out, which helps to protect indoor spaces from the elements while optimizing daylight penetration.

This project, like others, also took advantage of prefabricated building components that are assembled in the south, then shipped to the north. With no easy way to return these parts to the factory if errors are discovered onsite, the designers take extra care to identify problems in advance. “We need to have perfect construction drawings while making sure there will be no extras, and also work very hard with the contractor, who makes sure that all the shop drawings are good,” said Orzes.

Designing for a fast-changing climate

Building in the north is becoming even more difficult as the climate changes. Shifting weather patterns are making the construction season shorter, while melting permafrost is altering ground conditions. “It’s getting really complicated to find a way to pour the foundation of the building,” Blouin said.

For a current project, the firm is working with the Kativik Municipal Housing Bureau to understand whether thermosyphon technology, which sucks heat from the ground and releases it into the air, could be used to artificially maintain the permafrost below buildings over time.

“We’re really happy to be part of these experimental projects,” said Blouin. “We’re not sure if this is the best strategy, but we will go through it and see how it will behave in the coming years.”

“This is how construction in the north is going to look from now on,” he said. “It’s really a period of big changes.”

Explore

Wadi Hadramut: Cities of earth

Ronald Rael writes about the architectural culture of Wadi Hadhramaut, Yemen, which has remained devoted to its traditions of building with earth.

Anticipating, negotiating, conditioning: Tidal infrastructures of Patagonia

Melanie Kaba travels to "the end of the world" to investigate structures in Patagonia’s harsh coastal environments.

The relocation of Taro Island

As rising seas threaten the Solomon Islands, one community is planning a move to higher ground.