Image and meaning

An interview with Architecture Office, winner of the 2017 League Prize.

The League Prize, an annual competition that asks young designers to respond to a given theme, has marked an important milestone in many architects’ careers since it was established in 1981. Winners showcase their work through a lecture series and exhibition.

Architecture Office, a firm based in Syracuse, New York, was one of the 2017 prize recipients. Cofounders Jonathan Louie and Nicole McIntosh discussed their work with the Architectural League’s Akiva Blander and Catarina Flaksman.

Blander: This year’s League Prize theme is “Support.” What does it mean to you and your work?

Louie: The title of our proposal for this year’s Prize is There, There. It draws on the support of a pervasive image culture to construct new designs that question what a thing signifies in relation to its intent.

Images are fundamental elements of today’s world. But because of saturation, the image no longer stands alone as a single legible unit of meaning.

We aim to create images that both distinguish and deny the form, material, surface, and structure of things from their disciplinary and cultural associations.

Blander: Can you talk about how some of those concepts are reflected in your installation for the League Prize exhibition?

McIntosh: Our installation is called Viewfinders. It’s named after the part of the camera that frames the view of a subject.

With the installation, we were interested in expanding the visitor’s field of vision to reveal part of our archive: a selection of photographs, screenshots, movie clips, etc. We included highlights from four image sets that look at their corresponding models. Each one alters the field of view to collapse other “theres” with the “here.”

That’s why the proposal was called There, There. While none of these things are exactly what we have in mind for the final project, all this material reveals something about our design process.

Like the imagery that it projects, each viewfinder combines things that take on a new identity: a Sunpak traveling tripod, molded plastic downspout fittings, matte black paint, gaffer tape, and custom connections.

Blander: Can you talk about the process of combining these different artifacts and images?

McIntosh: We are really interested in readily available things around us. We work a lot with images; we collect images of all kinds. So this exhibition was a way of expanding the representation that we’re used to as architects or designers—elevations, sections, plans—to give more background on how we work.

The design process is really important to us. Maybe even more so than the final product.

Louie: The artifacts and images we selected really had to do with what we could find around us. We went to Home Depot; we searched Google. Ultimately we were just looking for things that were reminiscent of framing a view.

The result is not about the identity of each individual thing we purchased; it’s about combining those things to produce a new identity, putting the objects we make in flux between multiple instances.

McIntosh: The details are really important for that. How do you de-familiarize this image in order to create a new identity? That’s very consistent in our projects.

Blander: Some of your works bring a performative aspect to architecture—Big Will and Friends and Parti Wall. Human engagement seems to be central in how the works are experienced and, I assume, developed.

McIntosh: We’re interested in how the value of things changes over time, whether it’s years, days, or minutes. We’re also interested in how these shifting identities put productive pressure on their settings.

So all our work is performative, in a way, and every project creates a relationship with its surrounding environment.

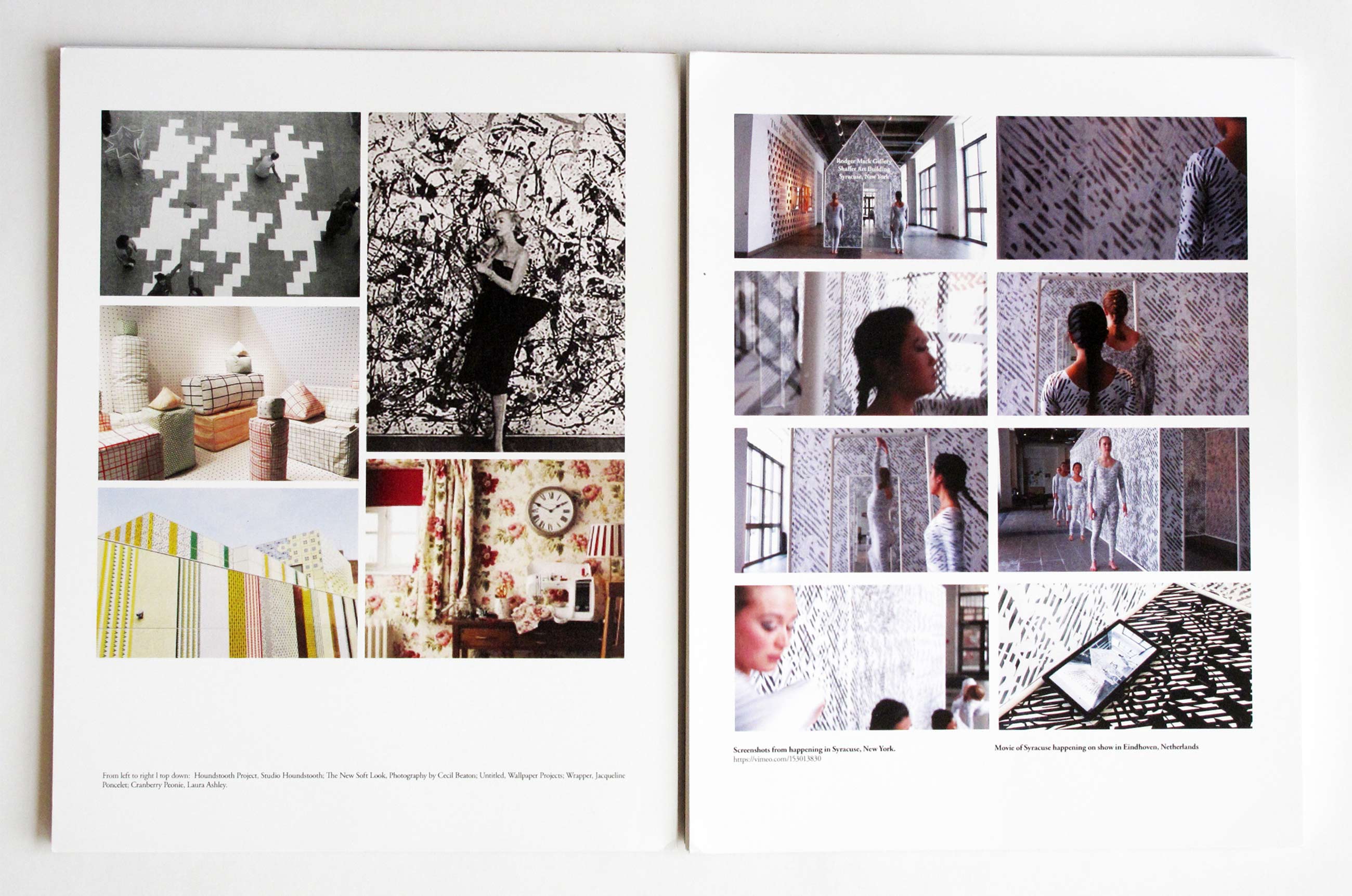

In Big Will, the wallpaper produces its environment and the performers push and pull the setting with each performance, perceptually altering the depth of the piece through the imagery on the surfaces of the walls and bodies.

But we’re also interested in the way the identity of something changes relative to the cultural and physical environment it sits in.

Blander: You installed Big Will and Friends in Eindhoven, in the Netherlands, as well as in Syracuse. Did you notice differences in the different settings?

Louie: One of the things that’s important with that installation is that daylighting changes over time. So the way we perceive the material, the way the material plays with the image, changes based on the time of day and location.

The other thing that’s specific to a site is the performers we collaborated with. In Syracuse, we collaborated with choreographer Stephanie White, whose background is in African American modern dance. In Eindhoven, we collaborated with ballet studio Valentijn.

So the way you perceive the environment that Big Will constructs is different based on what “friends” are within it.

Blander: We’re interested in the project Are We There, There? and its examination of European typologies in America. Can you speak a little bit about the production of this work?

McIntosh: It has to do with the role of observation in our office. We observe to gather information about things around us, but also about things that we didn’t really see.

Are We There, There? started with a road trip across the country, when we went to European American towns. One town stood out to us: New Glarus, also called Wisconsin’s Little Switzerland. It was founded in 1845 by Swiss immigrants.

We are interested in this theming of the American city with foreign cultural aspects, and in how Swiss imagery gets translated into ordinary local construction techniques, and what that image or setting becomes with these cultural associations

We’re currently documenting these Swiss-themed building codes that impacted the way New Glarus looks today: Swiss–American. To show this, we’re building very detailed corner condition models that show these façades that mimic Swiss imagery.

Architecture Office installation at the League Prize exhibition showing model of a façade mimicking Swiss architecture. Credit: David Sundberg/ESTO

Flaksman: What’s the relationship between architecture, installations, and exhibitions in your work?

McIntosh: As a young office, exhibitions are a way to test our ideas. It’s faster than planning a building, and has other productive pressures that are not from the client or building industry. Also, the smaller the scale, the more we are able to control every single detail.

Louie: Also, what’s interesting about collecting things that go into an exhibition, as well as designing the exhibition itself, is that it’s an opportunity for two things to merge. Oftentimes it’s in a very literal way.

We’ve been really fortunate to be at Syracuse University, because we end up designing exhibitions for the school, and that allows us to test out a number of our ideas.

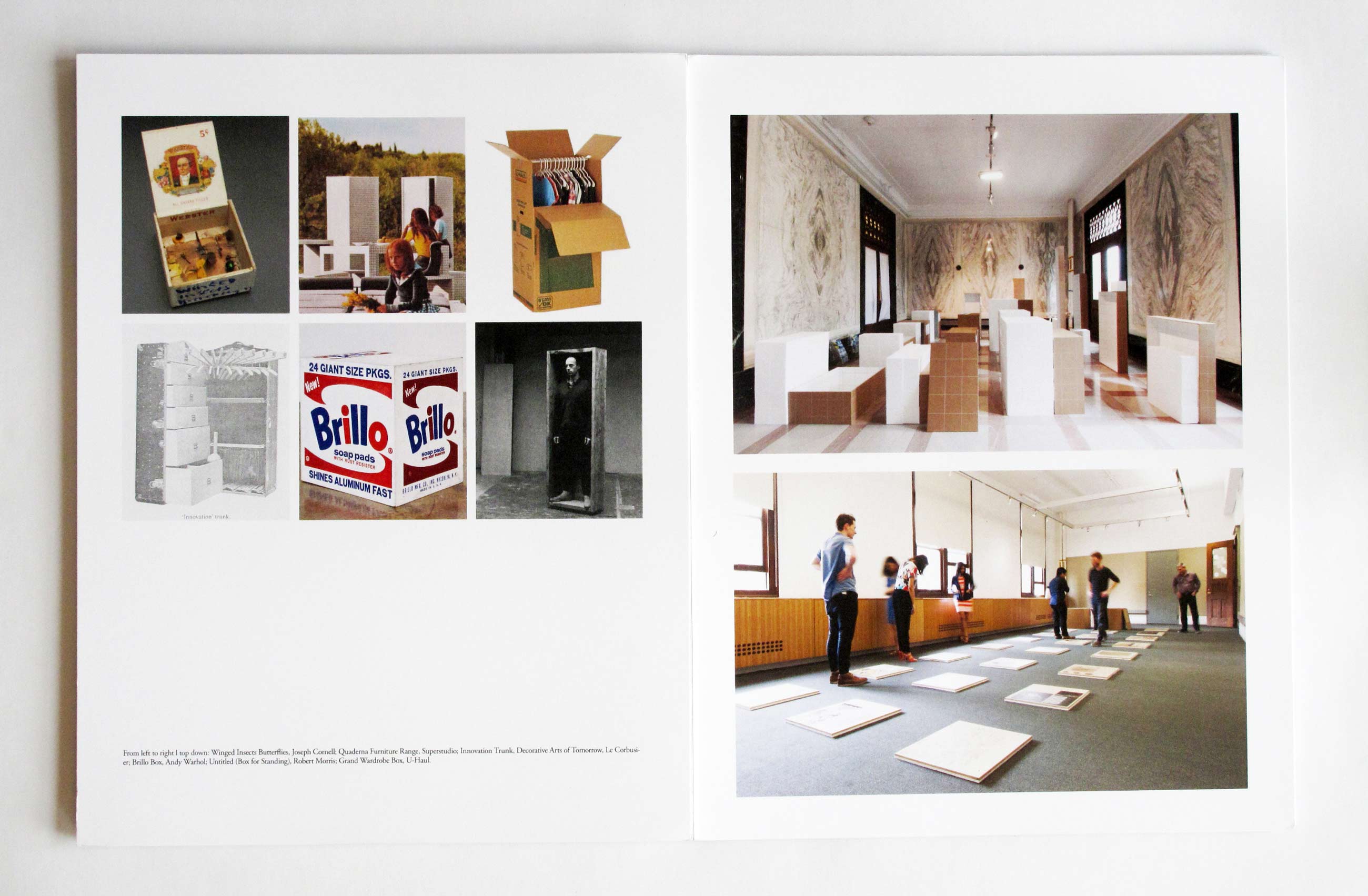

Oftentimes, with the exhibitions—including Trunk Show—we find something that is readily available and collect images around it. We use these images to examine, for example, assumptions about what a box does. That’s super fascinating for us as a young practice.

Blander: What or who are your main influences?

McIntosh: That’s a difficult question. They vary based on the projects we are working on.

Usually we start with a hunch or observation that influences the collection around a theme. But we’re consistently looking for influences that cross-pollinate between one position or place and another.

Recently, we have several images we’ve been particularly fascinated with. Jonathan just mentioned the Trunk Show: Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box as a medium for art that deploys the imagery of throwaway packaging is one.

For Are We There, There?, we’ve been looking at settings from Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel that are constructed from analogies to typical Hungarian building elements. Cecil Beaton’s Vogue fashion shoots that use Jackson Pollock’s paintings as a background wallpaper were an inspiration for Big Will. For the outer shell of House in House, we’ve been looking at Dan Graham’s photo article published in a magazine that documents American tract homes as a serial system.

But these things change over time.

Louie: And I wouldn’t put one photo to one project. Ultimately, these are all just things that we’re fascinated with, and they find their way into projects in different moments. One image collection can cross-pollinate with another. But ultimately, we try to be very strict with the framework of influences for each of our projects.

Blander: How do you see your practice developing throughout the next few years?

Louie: We have a few things coming out. In particular, the All Square restaurant in Minneapolis opens this spring. It’s a nonprofit fast-casual restaurant that employs formerly incarcerated individuals.

Our design frames different scenes that construct views and spaces within the restaurant. We are interested in deconstructing the picture from the frame to produce a variety of visual and physical relationships that play on several things: the actual and illusory space, the server and the visitor, and the restaurant and the city.

McIntosh: I think the most important thing for the future is that we have the freedom to do what we believe in or enjoy. We take our work really seriously, but we also have a lot of fun doing it.