To our future Wild and Wonderful West Virginia kin,

We dedicate this American Roundtable report to you. In the context of the current global pandemic, overdue racial reckoning, and visible climate change, we collectively propose a vision of an alternative future for the state of West Virginia. We envision a post-carbon future, 100 years from today, that leverages the resilience of our state’s people and places—our communities—and builds upon its greatest asset—land.

West Virginia is defined by its land. The state’s hills, hollers, valleys, rivers, creeks, and forests have been deeply embedded in the culture of our communities for generations. The mountains are a point of pride. The valuable resources below their surfaces attracted our ancestors and supported an age of prosperity that defined our state’s economy and culture for decades. But the depletion of coal, oil, gas, and timber—as well as the prioritization of short-term profits over long-term economic sustainability—has perpetuated a cycle of boom and bust. This rhythm has left our landscapes scarred, our communities abandoned, and generations struggling to redefine the future.

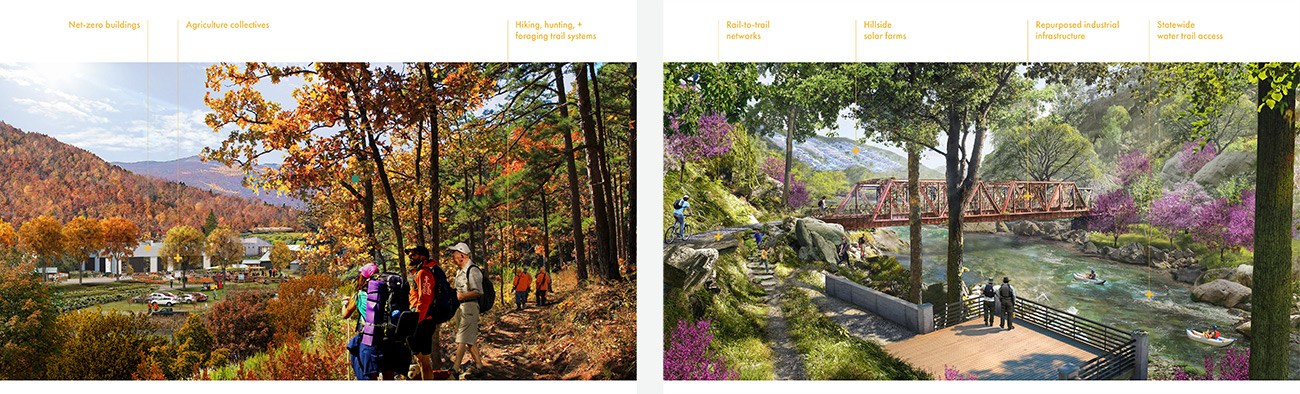

How can we build momentum for an alternative future that prioritizes the uniqueness and resilience of West Virginia’s people and places? What if our shared reverence for land is leveraged toward designing new relationships with the state’s natural resources instead of extracting them? On the same ground that once harbored the country’s most diverse forest ecosystems,1Gabriel Popkin, “The Green Miles,” The Washington Post Magazine, February 23, 2020. West Virginia’s landscapes could again become its greatest assets. Networks of recreational landscapes, sustainable forestry initiatives, solar farms, agricultural collectives, and outdoor ecotourism regions could redefine our relationship with land. By moving away from extraction and toward attraction, we can regenerate our fractured landscapes, prepare for the impacts of climate change, and create new sustainable economies for the people of West Virginia.

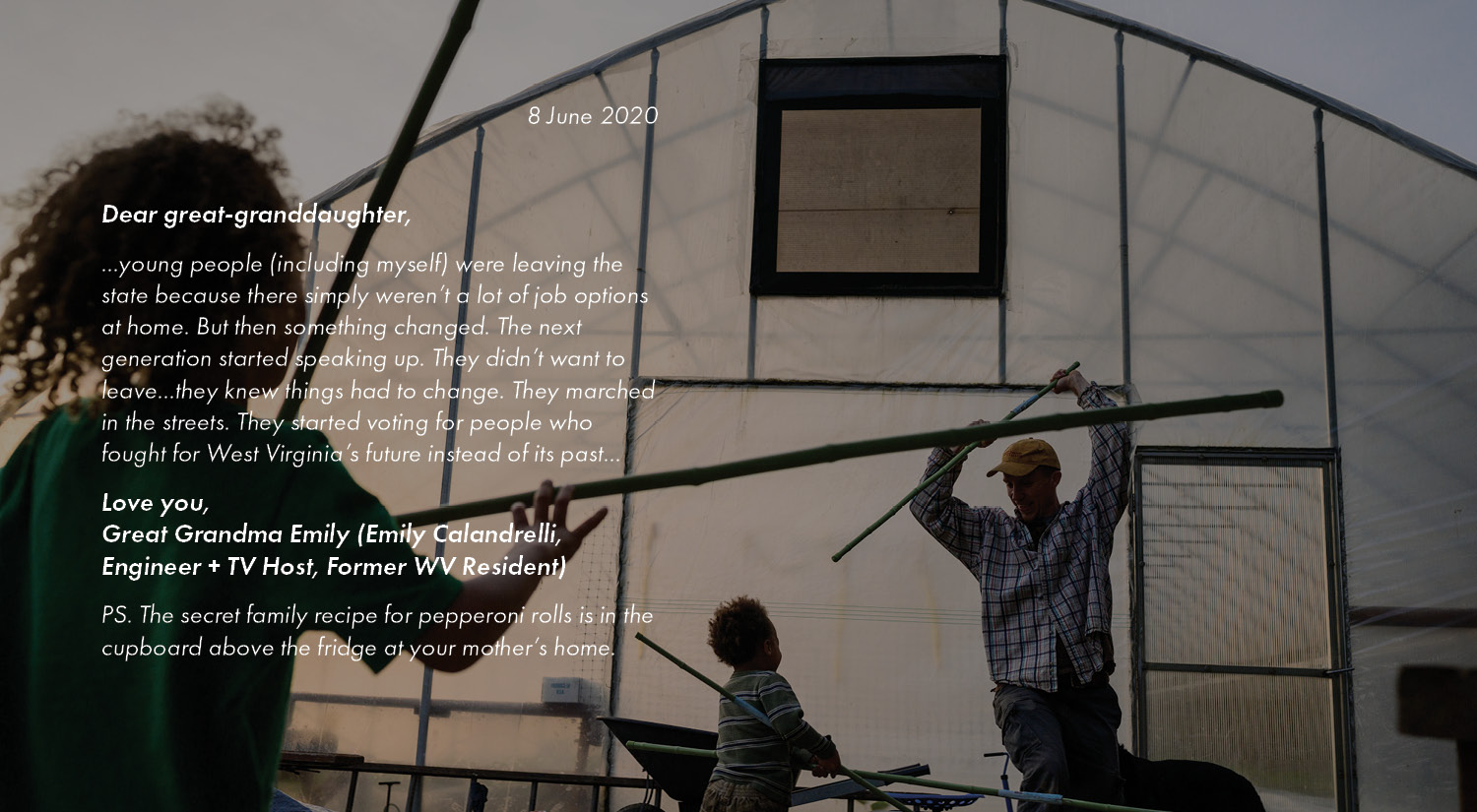

This land-based vision is inspired by input from current and former West Virginia residents. Throughout the summer of 2020, we invited West Virginians to shape alternative narratives for the state by writing letters to future family members residing in the state in the year 2120. These speculative futures offer glimpses into their collective hopes and dreams—clean streams filled with salamanders, statewide passenger train networks, solar and nuclear energy jobs, fertile soil for home-grown produce, well-funded public health care systems, recreational tourism to rival the Rockies, and secret pepperoni roll recipes.

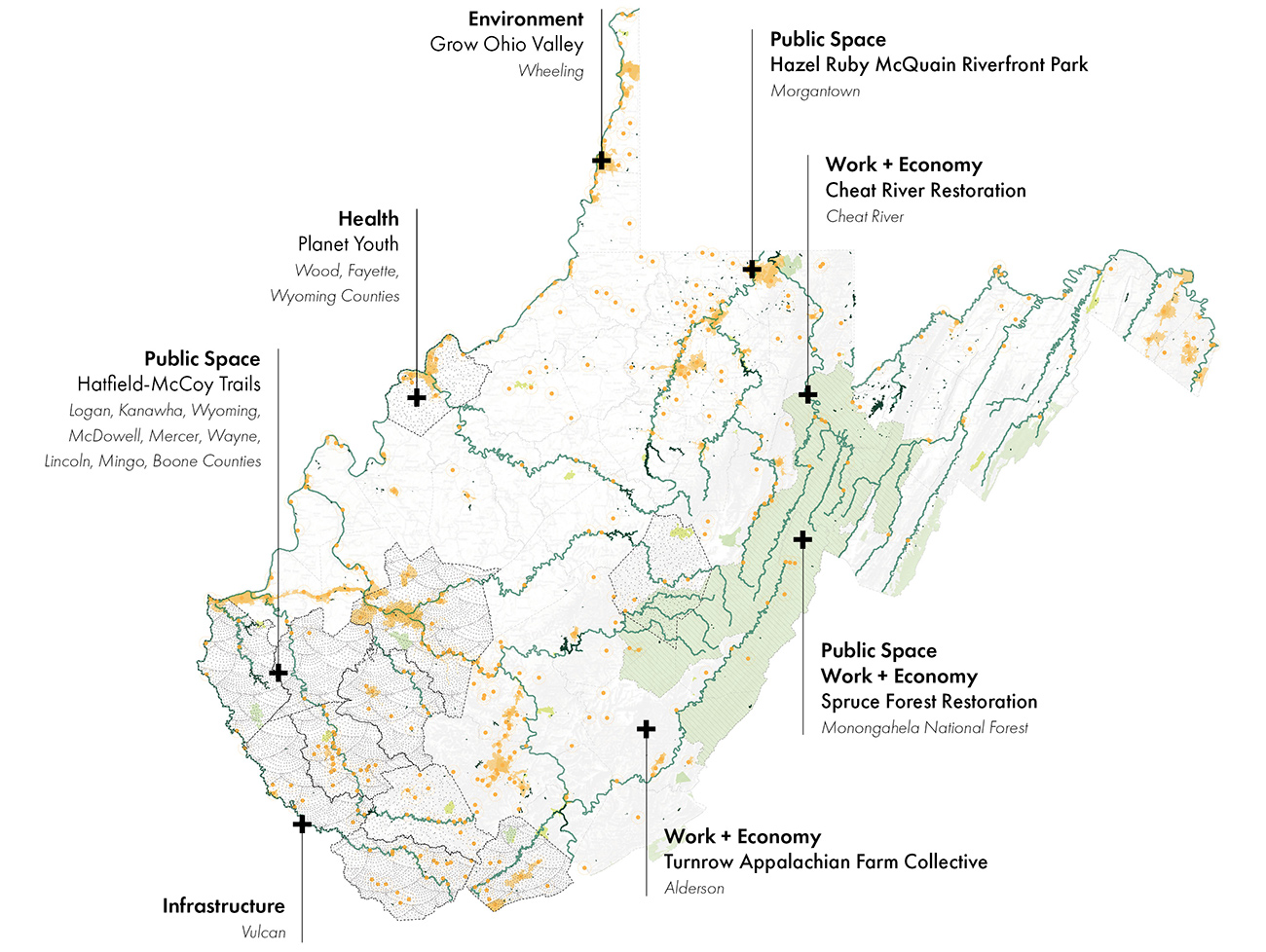

This American Roundtable report aims to build momentum toward these imagined futures in two parts. First, we document the history of West Virginia’s land use while visualizing inspirational land-based futures. Second, we provide an interdisciplinary perspective on communities where emerging land-based projects are already countering the state’s declining extraction economy. These projects—all currently operating—include new forms of infrastructure, recreational landscapes, reforestation initiatives, urban agriculture, and renovated public spaces. Through the lens of the American Roundtable themes (Infrastructure, Health, Work and Economy, Environment, and Public Space), five local contributors document the successes, failures, and opportunities of these ventures, showcasing the people and programs actively creating sustainable alternative futures.

We hope that the landscapes imagined and the projects documented in this report can help build momentum for a future West Virginia that is even wilder and more wonderful than it is today.

—The Appalachia Rising editorial team

Appalachia’s narrative has historically been defined by outsiders. We aim to provide a more diverse perspective by documenting alternative landscape futures grounded in West Virginia communities.

For many, the name West Virginia conjures images—created by outsiders and perpetuated by national media—of rural poverty. These stereotypes of Appalachians have persisted for decades, from the hillbillies often associated with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty to the overly simplified excuse for President Donald Trump’s ascendance perpetuated in J.D. Vance’s 2016 Hillbilly Elegy.

Encouragingly, there is a growing movement from within the state to highlight more diverse and nuanced perspectives. Residents, academics, advocates, and documentarians are reclaiming West Virginia’s story and acknowledging contemporary challenges while offering hopeful outlooks for the region. In direct response to Vance’s elegy, Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll’s 2019 book Appalachian Reckoning provides an inclusive collection of essays, creative writing, and art dedicated to highlighting the region’s “intellectual vitality, spiritual richness, and progressive possibilities.” Roger May’s nationally acclaimed crowdsourced photography project Looking at Appalachia continues to establish a visual counterpoint to stereotypes of the region. ReImagine Appalachia, a coalition of over 50 Appalachian organizations, has proposed an equitable economic blueprint for a twenty-first-century Green New Deal economy, built by and for the people of Appalachia.

We aim to contribute to West Virginia’s expanding narrative. While cultural counterpoints emerge across the state, design has been noticeably absent from the conversation. Designers—specifically, landscape architects and architects—are uniquely positioned to work alongside community members, political leaders, funders, and allied professionals to document, propose, and visualize alternative futures.

Designers—specifically, landscape architects and architects—are uniquely positioned to work alongside community members, political leaders, funders, and allied professionals to document, propose, and visualize alternative futures.

This report, led by local landscape architects in collaboration with West Virginia–focused documentarians, is committed to understanding existing relationships with the natural and built environment and envisioning new relationships that have the potential to inspire alternative land-use futures.

West Virginia is a state of small communities with a history of extractive land-based economies.

As the only state contained entirely within Appalachia, West Virginia represents a microcosm of postindustrial challenges. The state comprises 232 communities2 United States Environmental Protection Agency, “What Climate Change Means for West Virginia.” ranging in population from 5 to almost 50,000.3Thurmond has the state’s smallest population, with five residents. Charleston, the state capital, has the largest population, 46,536.4United States Census Bureau, “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in West Virginia: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019.” Historically, the industrial boom and bust cycles of the timber, coal, oil, and gas industries kept many West Virginia communities in a perpetual rhythm of speculation and decline. While the extraction industry has been a source of pride, defunct mines and abandoned gas wells have left shrunken towns, vacated main streets, and eradicated ecosystems in their wake.

Like many American industrial narratives, the story of West Virginia begins with geology. More than 300 million years ago, the region was home to a lush mountain ecosystem.5 Leopold, Joe and Christopher Wilkinson. Roadside Geology of West Virginia, Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2018. Over time, as the tall Appalachian Mountains became low hills, sea levels rose and submerged the state. The cyclical rise and fall of the oceans and the burying of plant life slowly formed the Appalachian Mountains of today and established the natural resource deposits that became the foundation for coal, oil, and natural gas industries.

The landscape and its resources attracted West Virginia’s first inhabitants. Starting in 10,500 BC, the land supported the communities of the Iroquois, the Shawnee, and the Cherokee.6Maslowski, Robert F. “Indians”, e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia, West Virginia Humanities Council, 2006; accessed December 28, 2020. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, colonial settlement patterns developed around resources, and communities were defined by their proximity to valuable timber tracks and rich coal seams. The timbering of trees fueled the heating of new residents’ homes, and the clearing of forests made way for a growing agricultural economy. In the early nineteenth century, residents began using coal in their homes, spawning the rise of the coal industry.

Over the next two decades, this industry both flourished and faltered. The fast pace of extraction at the beginning of the twentieth century led to the proliferation of company towns: isolated communities built by and for the coal companies. Grocery stores, schools, recreational facilities, even churches were all built or owned by coal companies. Consequently, the communities were wholly dependent on the for-profit manufacturing of coal to survive. By 1917, West Virginia had produced 89.4 million tons of coal, employing 90,000 miners to keep up with production.7Lewis, Ronald L. “Coal Industry”, e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia, West Virginia Humanities Council, 2006; accessed December 28, 2020.

As early as the 1930s, the industry began to decline. The National Labor Relations Act granted workers the hard-fought right to unionize. Coal companies were no longer able to capitalize on the exploitation of workers as flagrantly as they once had, causing the cost of extraction to rise. Concurrently, the Great Depression reduced the national demand for coal and its byproducts. As the mining industry shuttered, so did the company towns. Housing and community services were sold off or abandoned, transforming once-booming towns into vacant shells of their former selves.

By the mid-twentieth century, the mining industry had been transformed by automated mechanization. With automation, production grew, but the demand for labor fell. Between 1950 and 2000, the number of coal miners in West Virginia declined from 127,000 to 18,000.8Lewis, “Coal Industry.”

In recent decades, the coal industry has fallen behind other natural resource industries as the extraction of natural gas has become cheaper and more accessible. Over the last 10 years, coal production in the Appalachian region has declined 50 percent and coal mining employment has fallen 20 percent. Although West Virginia remains the nation’s second-largest coal producer and sixth-largest natural gas producer, both industries are expected to plateau or continue to decline.9Bowen, Eric, Christiadi, John Deskins, Brian Lego. “An Overview of the Coal Economy in Appalachia,” Appalachian Regional Commission, accessed December 17, 2020.

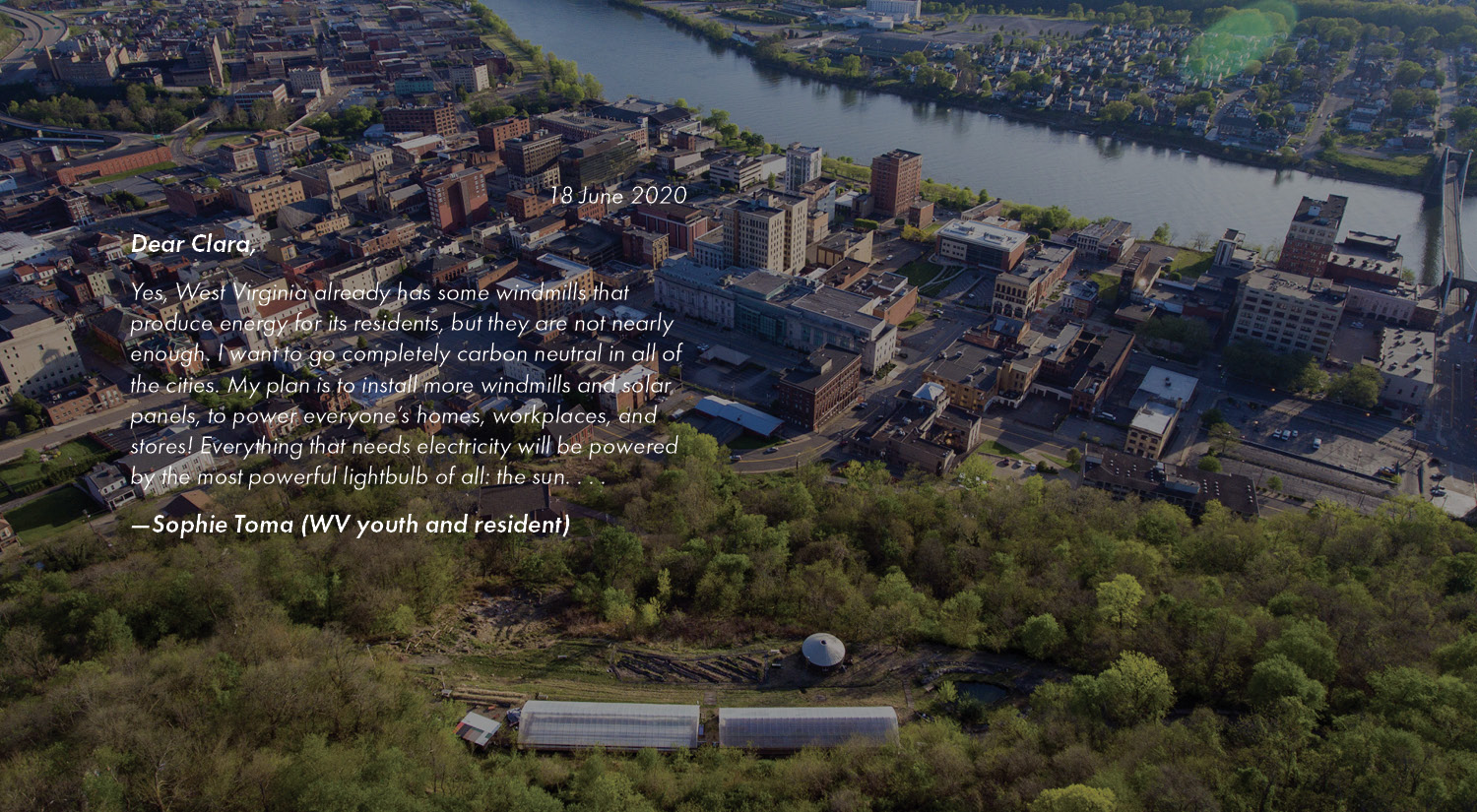

As extraction industries wane across the state, leaders look to land-based economic alternatives such as renewable energy generation and recreational tourism as future growth sectors. While only 5 percent of the state’s electricity generation is produced from hydroelectric, wind, and solar power, renewable energy generation has grown by more than 10 percent since 2018 and is expected to continue to grow.10Sierra Club, “Clean Energy Works in West Virginia,” accessed December 17, 2020. The outdoor recreational tourism industry has also proved increasingly valuable. Many of the state’s recreational destinations are within three-hour drives of major US cities including Washington, DC, and Pittsburgh. Activities such as whitewater rafting, hiking, mountain biking, camping, and riding all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) contribute over $9 billion in consumer spending annually in the state. Today, twice as many jobs in West Virginia depend on the outdoor recreation industry as on the coal industry.11Outdoor Industry Association, “West Virginia Outdoor Recreation Economy Report,” accessed December 17, 2020.

West Virginia is getting wetter, warmer, and greener.

As the economic landscape of West Virginia continues to shift, global warming provides another argument for a land-centered future. Over the next 100 years, climate change is expected to dramatically affect communities across the state. Annual temperatures will increase, causing faster-melting snows, greater evaporation rates, and drier soils. Frequency and intensity of rainfall will increase, causing more-frequent floods, landslides, and mudslides. Ecosystems will shift as temperature and precipitation patterns change.12United States Environmental Protection Agency, “What Climate Change Means for West Virginia.”

But West Virginia’s landscape is poised to provide unique solutions to address the region’s vulnerabilities. The Nature Conservancy has identified the state’s highland forests as one of the most climate-resilient habitats in the country.13The Nature Conservancy, “Natural Climate Solutions in West Virginia.” Because of the ecosystem’s ability to withstand future climate change impacts, the landscape has the potential to become a key source of mitigation through carbon sequestration, habitat migration, and forest management. These strategies have the potential to offer co-benefits including job creation, increased tourism, and alternative sources of energy production.

We envision a post-carbon future in which West Virginia leverages land as its greatest resource.

How can West Virginia design its future to cope with an inevitably wetter, warmer reality? One answer is the same resource that defines the state’s economic history: its land. Inspired by the collective input of current and former residents, our designer-led team envisions a post-carbon future in which West Virginians leverage land as their greatest resource.

Networks of recreational landscapes, solar farms, agricultural collectives, ecotourism hubs, and sustainable forestry initiatives are poised to redefine the state’s future. Intentional design and planning of individual projects and strategic statewide systems could result in multifunctional public spaces, recreational networks, and sustainable energy systems that provide new jobs and positive public health outcomes. New ATV trails could cut through former mountaintop mining sites where reforestation programs restore ecosystems while providing jobs. Regional rail-to-trail bike paths could run parallel to recreational river networks. Mountainside solar farms could provide energy locally and regionally. Hiking trails could strategically connect communities to farms, hunting grounds, and foraging sites, benefitting both local residents and visitors.

The long-range coordinated planning necessary to realize these futures will take time, political will, money, patience, inspiration, and sustained vision. Collectively, we can heal broken landscapes with reclamation projects, prepare for the impacts of climate change by leveraging resilient habitats, and create new sustainable economies by offering just economic transitions away from extraction industries toward land-based outdoor industries. Through intentional design and planning, we can celebrate the state’s unique social and cultural identity and inspire our communities to meet their highest potential.

Features

Emerging land-based projects are actively shaping West Virginia’s future.

Through the lens of the five American Roundtable themes (Infrastructure, Health, Work and Economy, Environment, and Public Space), the five features in this report document communities where emerging land-based projects currently provide inspirational counterpoints to the state’s declining extraction economy. The features include individual project profiles documented through photography, maps, film, articles, and audio clips. The projects, chronicled by a diverse team of Appalachian documentarians, showcase the people and programs actively creating sustainable alternative futures on West Virginia’s land. With a focus on reframing the state’s relationship with land, the features highlight recurring themes of historic exploitation, land reclamation, Appalachian identity, recreation, food justice, and youth education.

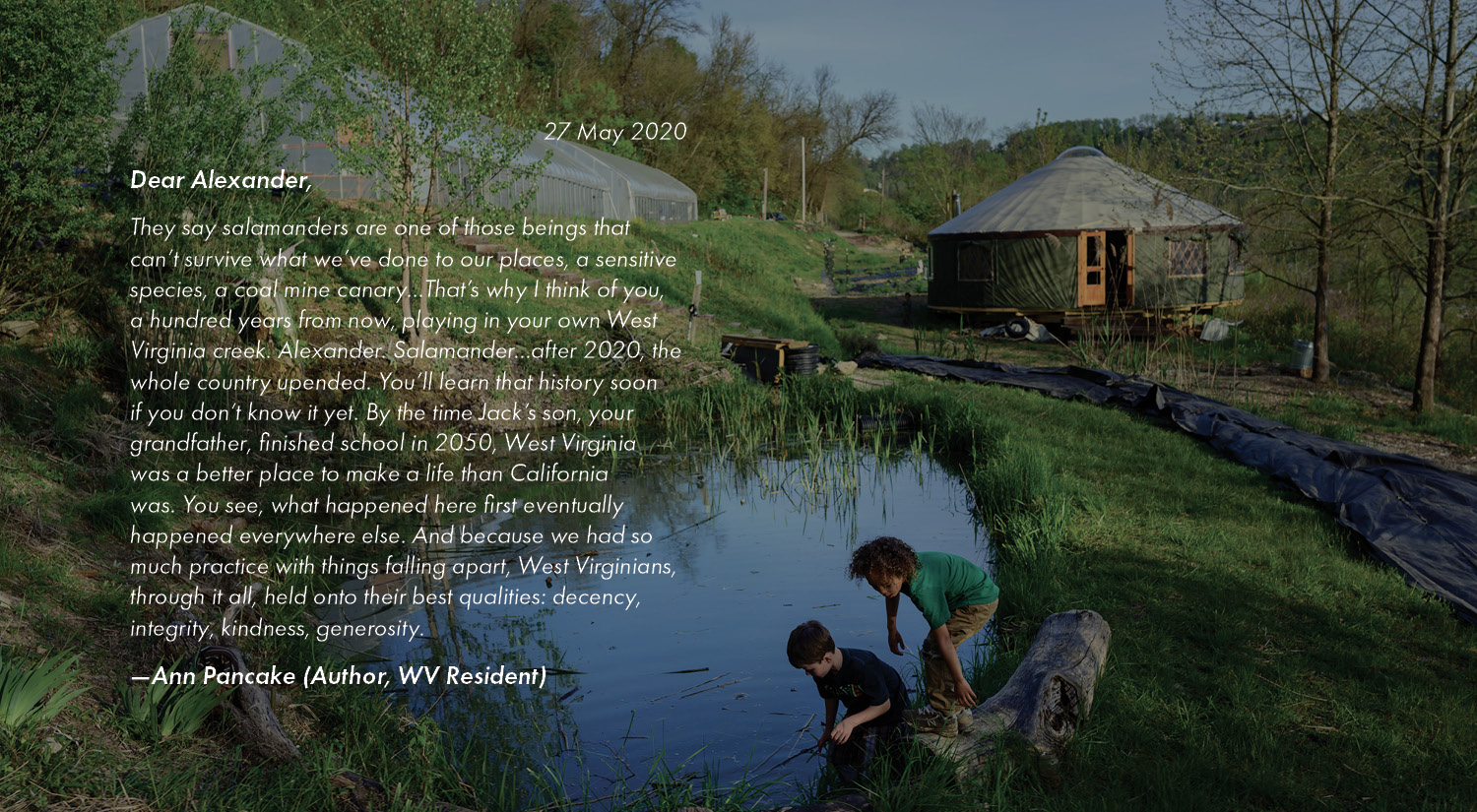

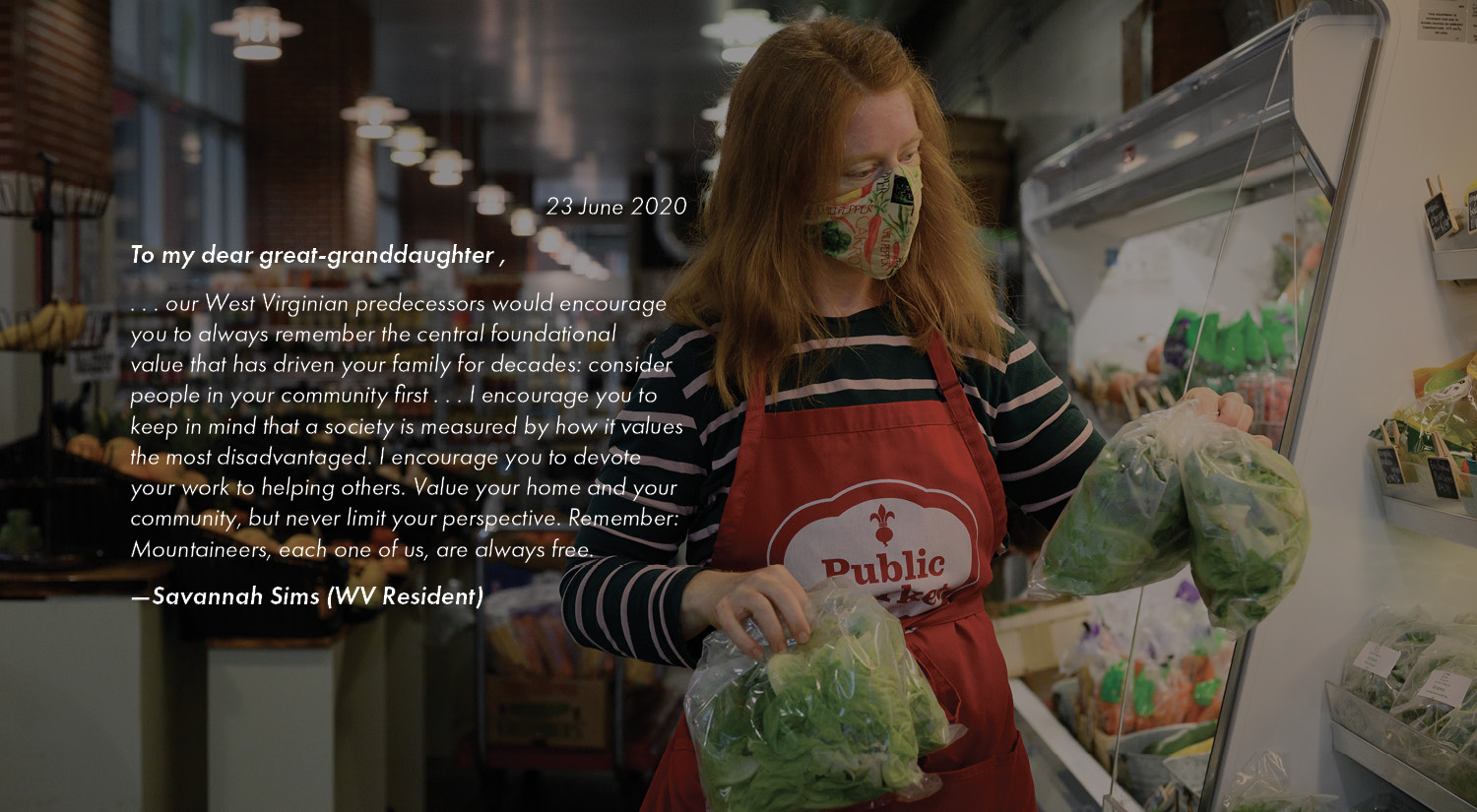

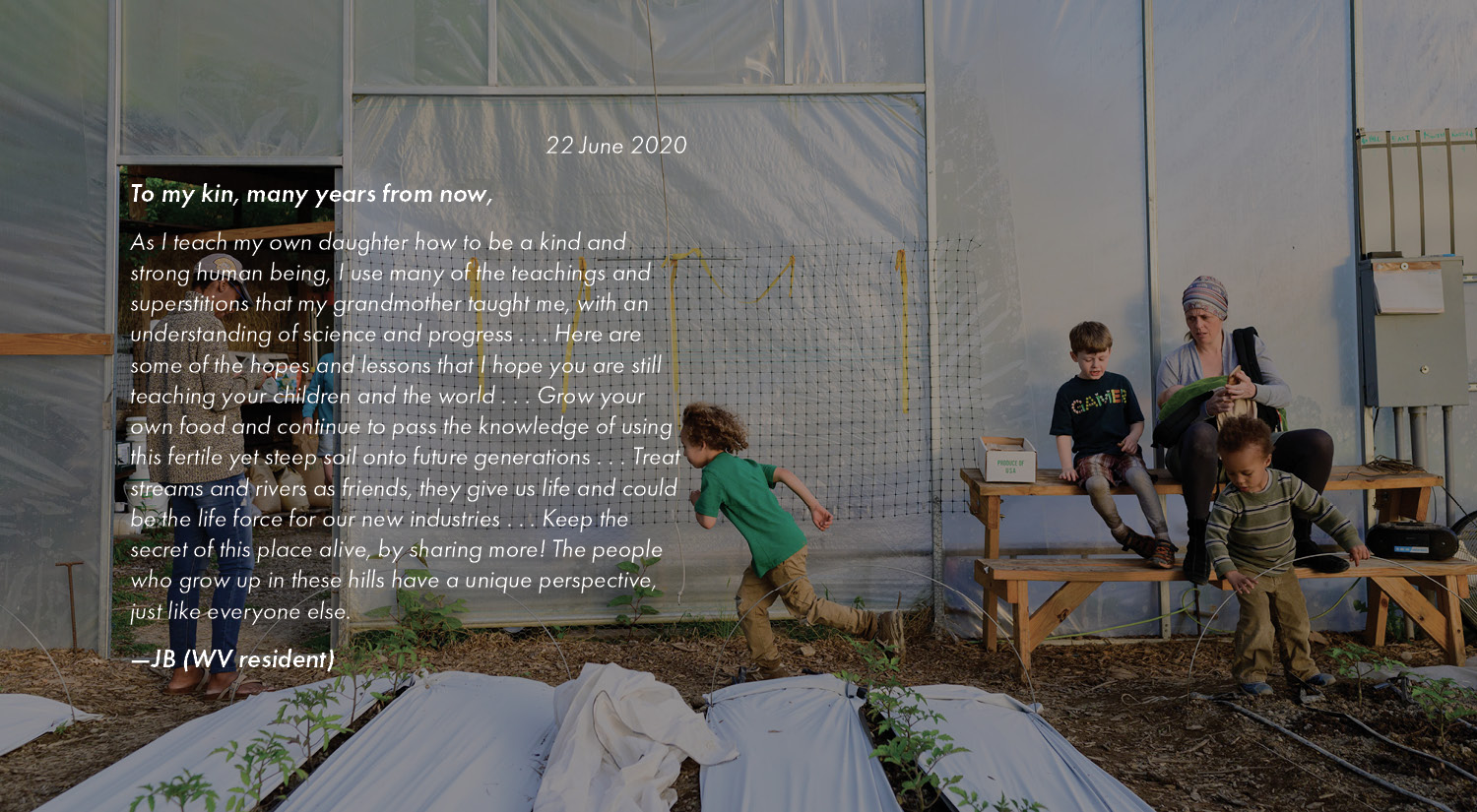

Each feature is introduced with a quote from a current or former West Virginia resident who was invited to write a letter to a hypothetical relative living in the state in the year 2120. Collected throughout the summer of 2020, the letters paint a hopeful picture of a future West Virginia—a future that is grounded in community and prioritizes sustainable infrastructure, well-supported public health systems, new economies, healthy environments, and thriving public spaces.

The Appalachia Rising team is composed of nationally acclaimed documentarians, writers, and creatives with Appalachian roots and a professional focus on West Virginia. An all-woman slate, this group is dedicated to expressing alternative narratives about Appalachia, specifically West Virginia. The collaborators include designer and researcher Caroline Filice Smith, videographer Elaine McMillion Sheldon, journalist Brittany Patterson, photographer Rebecca Kiger, and landscape architecture firm Merritt Chase, led by Nina Chase. Sarah Rafson and her team at Point Line Projects provided editorial guidance for the project. The group represents a cross section of diverse voices, perspectives, and mediums for creative work.

Through a series of writings and mappings, Caroline Filice Smith explores the history of infrastructural investment in West Virginia communities marked by decades of precarity and neglect. West Virginia’s infrastructure has long been defined by the rapid success and subsequent decline of the coal industry. What happens to planning and design when the promise of progress has faded? What infrastructure is needed, and who steps in? She posits that reframing the landscape as necessary foundational infrastructure is necessary for the state’s future success.

In a powerful short documentary film, Elaine McMillion Sheldon addresses public health in West Virginia through the story of grant-funded youth programs that temporarily provide short-term after-school activities for kids. Featuring interviews with former participants as well as the recent long-term work of researcher Alfgeir Kristjansson in Wood, Fayette, and Wyoming Counties, the film paints a picture of communities left behind when public funding and short-term programs cannot meet their needs. Highlighting the natural beauty and outdoor recreational assets available across the state, McMillion Sheldon’s work advocates for sustained investment in structured outdoor recreation in order to dramatically improve public health and reduce drug use across the state.

Through writing and audio clips, Brittany Patterson profiles three experimental land-based ventures that provide economic benefits and novel work opportunities across the state. The restoration of the Cheat River across northern West Virginia, the reforestation of spruce forests in the Monongahela National Forest, and the establishment of the Turnrow Appalachian Farm Collective in Aldersen offer hopeful examples of how innovative approaches to landscape-based projects can provide outlets for recreational tourism, climate change mitigation, and sustainable agricultural systems.

Rebecca Kiger’s vivid photography captures the impact of Wheeling-based urban agriculture initiative Grow Ohio Valley, led by Danny Swan. Kiger’s photography begs the question: How can the environment provide a source of inspiration in places where the landscape has been systematically dismantled and exploited? Grow Ohio Valley has become a regional model for thoughtful urban farming by repurposing a variety of urban environments (vacant lots, steep hillsides, former vineyards, and traditional farms) for food production. In tandem with maximizing the potential of these unique urban landscapes, the organization has addressed the systemic need for equitable access to healthy food by building a robust food distribution network that includes a mobile food market and the brick-and-mortar Public Market in downtown Wheeling.

The team at Merritt Chase questions what defines public space in Appalachia and offer perspectives on how public spaces can support the region’s future by celebrating the unique identity of a place. Through three project profiles, this feature explores the variety of scales of West Virginia public spaces. The history of the Monongahela National Forest offers an example of regional preservation and conservation efforts in eastern West Virginia, while the Hatfield-McCoy ATV Trails System illustrates a multi-county effort to attract tourism to the state’s southern former coalfields. Additionally, the recent renovation of the Hazel Ruby McQuain Riverfront in Morgantown provides an example of how partnerships and community-led planning led to tangible citywide benefits.

Biographies

is a principal and cofounder of Merritt Chase, a landscape architecture and research practice based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A native of Morgantown, West Virginia, Chase is a graduate of West Virginia University and Harvard University Graduate School of Design. She works across Appalachia to plan and design public realm projects, including regional park master plans, riverfront parks, and trail systems.

The views expressed here are those of the authors only and do not reflect the position of The Architectural League of New York.