A Cooperative Housing Movement Inspired by Barcelona’s Anarchist Heritage

Eliseu Arrufat Grau discusses the origins and philosophy of Lacol, a Spanish architecture firm focused on cooperativism.

May 8, 2023

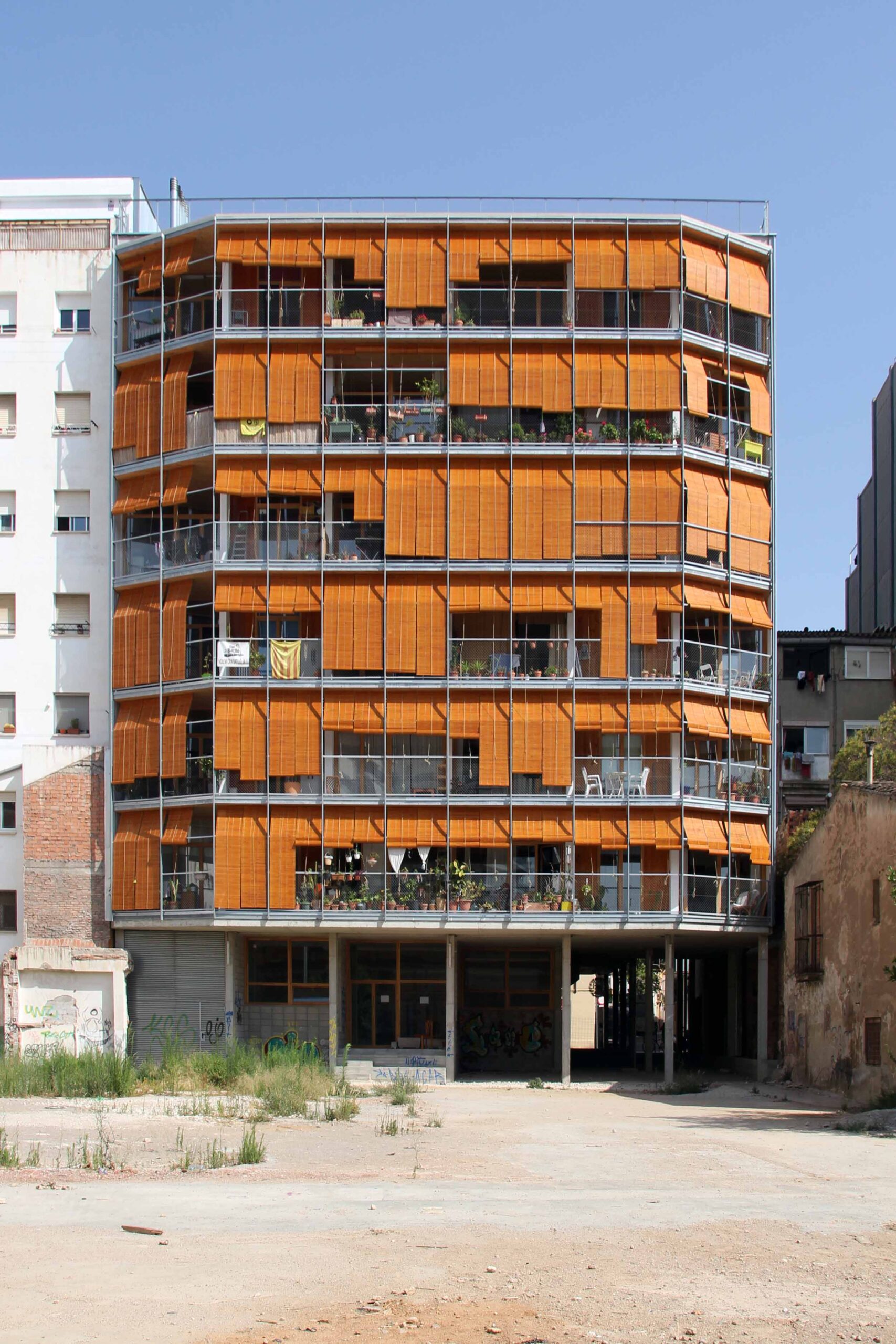

Apartment in La Borda, a 28-unit housing cooperative in Barcelona designed by Lacol. Image credit: Alvaro Valdecantos

Current Work is a lecture series featuring leading figures in the worlds of architecture, urbanism, design, and art.

Barcelona firm Lacol specializes in the design of cooperatively owned and operated buildings, helping local groups develop their own housing, workplaces, and cultural spaces. Established in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, the practice draws heavily on the long tradition of working-class collectives in the Sants neighborhood, where its offices are located.

In November 2022, two of the firm’s 13 partners, Cristina Gamboa Masdevall and Eliseu Arrufat Grau, presented their projects in a Current Work lecture. After their talk, they answered several questions from audience members, but ran out of time before they could respond to the full list.

In an attempt to address as many of the remaining queries as possible, the League’s Alicia Botero and Sarah Wesseler conducted a follow-up interview with Arrufat.

*

Alicia Botero: Several people who attended the lecture asked for more information about the members of the housing cooperatives you work with. Could you tell us about their demographics and their motivations for joining a cooperative?

Eliseu Arrufat Grau: In terms of social status, it’s pretty diverse. The first cooperatives were more homogenous in terms of geographical origin and educational background. But as we do more, news spreads by word of mouth, and we have more examples, with each example trying to break some mold—so it’s been attracting more people.

At the generational level, there’s usually been at least some representation from all age groups. La Borda, the first project, has people of all ages. To the degree that Spain has any more-or-less established housing cooperative system, it’s for seniors: cooperatives for people who want to grow old in a community and not in typical rest homes, right?

But we have noticed some lack of representation in terms of ethnicity, or in terms of people who weren’t raised in Barcelona, or in Spain. So we’ve tried to diversify in this sense. Every time we do a new project, there are new people from outside the region. I think this is important, because it allows us to kind of avoid creating white ghettos—I don’t know the best way to say this.

And we’re also working with a cooperative of women and people related to the LGBTQ movement.

So it’s still early stages, but the cooperative housing movement is definitely sensitive to this issue, because they don’t want to just satisfy the needs of white middle-class, or almost middle-class, university graduates. There is a real interest in having the movement cross barriers that are very socially visible.

Botero: So the trajectory you’re describing is one of diversification, where initially it was largely white middle-class people from Barcelona, and now you’re bringing others in.

Arrufat: We’re talking about a process of self-organization. It’s not a paternalistic system, in the sense that you don’t just put your name on a list and there’s a management structure above you that handles the rest. In this situation, every member has to manage something.

So the difficulty of approaching a place that may not seem safe to you is something we’re trying to address. Not as architects, but as a cooperative housing movement.

Botero: You mentioned something about safety and I wasn’t quite sure what you meant. Could you explain this point?

Arrufat: Yes, I’m referring to, for example, a meeting where it’s almost all men and there’s a woman who has to give her opinion: This might not be a safe space. Or it can be an unsafe space if most people have a high level of intellectual capital and rhetorical skill but another person doesn’t, due to their past circumstances, due to not speaking the local language well, due to whatever. It can be an unsafe space when most people are very convinced of something, right?, and someone enters with doubts.

Botero: OK, great. And the second part of the question is, what motivates people to join the housing cooperatives?

Arrufat: I would say that there are two main categories of motivation. One is political: The desire to create an alternative to standard housing models of renting or buying. The desire to create new ties—the hope that architecture and the creation of this kind of housing can allow us to grow as human beings. I believe there’s a very clear desire to stop living in places that have been designed and conceived solely for economic benefit. We want societal benefits, right?

And the other is the impossibility of finding a house where you can live for a long time with the certainty that no one’s going to kick you out. In other words, the other motivation is need: the need for decent housing outside of the profit-driven market; housing that provides security regardless of ups and downs, regardless of whether Barcelona is a global city or whether there’s migration from the countryside . . .

And these two motivations intersect. I believe that almost no one comes in with only one goal. I think we all come to this with both, although different people might be motivated a little more by one or another.

Another motivation falls into the political category: the political necessity of breaking the nuclear family, creating new ways to care for oneself, establishing human relationships beyond father, mother, brother, sister, boyfriend, girlfriend. I believe that these are places that favor this type of investigation, of prototyping—of freedom, in the end.

Botero: Another topic several people asked about during the lecture was how the housing cooperatives finance their projects and what role Lacol plays in this process.

Arrufat: The main financial mechanism is the bank, but ethical banking in this case. What happened is that the bank we normally work with saw great potential in the cooperative housing movement. It was such an ethical bank that it was very limited in terms of project financing, so it changed its policies to be able to include this type of work. Because previously, they had a ceiling—I think it was €200,000 or €300,000—and when you’re talking about producing collective housing, this won’t get you anywhere, right? So they removed this ceiling and established very strict conditions to ensure that the project won’t lose this political vision of taking land off the speculative market to build housing.

To explain it another way: The Spanish constitution tells us that housing is a fundamental right, but when global liberalism comes into the picture, housing becomes a market commodity. And so [in Spain], we constantly move between the speculative and the fundamental. The bank, in this case, gives us money, but also requires us to maintain certain ethics with the housing produced with these funds. It’s a way to ensure the model isn’t corrupted.

And there are other financing mechanisms. For example, the laws governing cooperatives allow us to have various types of partners. La Borda has a thousand collaborating partners; the membership campaign was enormous, and each member could buy bonds that . . . I don’t remember the number now, but it was around €1,000. Well, a thousand members at €1,000 is €1 million. This was a very large mobilization of capital, beyond the purchasing power of the organizing partners.

And the third leg of the financing came from people who had capital and wanted the project to happen. There were some specific negotiations—not many—with people who could put in more money: €50,000, €100,000.

So there was some complex financial engineering, but that allowed us to get the €3 million that the building cost.

As for Lacol’s role, we try to never play the role of developer. We try to remain in the role of architecture. So, for example, generating images to get people excited, creating floor plans, or doing a study of what’s below the existing surfaces . . . everything related to imagining what the building could be like, we do in the preliminary phases.

The collaboratives we work with are organized; they know that they have to mobilize capital. And the first group to issue an invoice is basically the architects, because we’re the ones who will begin to really specify the dimensions and characteristics of each building. And from there, before arriving at the construction phase—which is the expensive point, the point that requires the most capital—with the information provided by the architects, it’s when the housing cooperatives go to the bank, when they go to look for more partners.

Botero: I imagine that since you have all this knowledge about different forms of financing, when groups don’t know how to proceed with their projects, you can guide them a bit.

Arrufat: Yes, but we try not to. There are other cooperatives that specialize in cooperative management.

After La Borda, we became part of the technical team of La Dinamo Fundació, which is a foundation dedicated solely to promoting cooperative social housing. What La Dinamo does is bring together all the actors you might need. So if the three of us set up a cooperative and we didn’t know how to create a financial plan, ask for a loan, or work with architects, we would go to La Dinamo and say, “Hey, I want to be part of La Dinamo, and I need help and advice.” And La Dinamo offers you a whole package: a schedule and assistance so that everything can happen within the timeline that the group specifies.

Botero: OK. Another audience member asked if you could offer advice about how to convince the principals of a traditional for-profit firm to take on work aimed at addressing social challenges. So we wanted to know if you have any answers for her, and if there are aspects of your work that you think would be difficult to achieve outside of a nonprofit cooperative practice model.

Arrufat: Wow. I don’t know . . . !

I know that the nonprofit structure isn’t very common among professional firms. But what it comes down to for me is just that I have a salary and I collect my pay, but there are some limits on my earning potential. There’s a salary range that I can’t exceed. If I exceed that range, the Spanish government will assume that I’m making a profit and revoke our nonprofit status. So my company, my cooperative, can invoice to infinity as long as the partners follow these rules.

So the fact that I work at a nonprofit isn’t what determines how I practice. The nonprofit structure determines how I make my living in terms of purchasing power, of not wanting to make myself rich with other people’s money, or, in some cases, with public funds. So I’ll never buy myself a Ferrari, right? I’ve accepted that I’ll have limits.

But I think that the question of firms working on socially driven projects is a separate issue. I believe it can happen in for-profit companies—I don’t see why not.

But it’s also true that my clients, the cooperatives—I don’t know if they’d hire me if I were a for-profit cooperative. I think they feel better knowing that I’m not going to make a profit.

But being a nonprofit doesn’t mean that I have to charge less, because one of the conditions we’ve established for ourselves is dignified labor. And the world of architecture, at least in Spain, is based almost in slavery, right? Half-day contracts for full days of work, students that don’t get paid, huge offices with no salaried staff . . .

So it’s complex, because the architectural discipline sometimes doesn’t understand itself as work—it thinks of itself as an artistic practice, and everyone has a tree at home that money grows on.

So that’s a very difficult question for me to answer, because it’s intertwined with many things. But yeah, more or less, I think it’s possible to differentiate between the way I want to use money and the architectural activity that I take on.

Botero: OK. And regarding the organization of the firm . . . Because you’re not only a nonprofit, but also a cooperative. So do you think firms like yours might approach social projects in a different way than firms that are more hierarchical in structure? Or not necessarily?

Arrufat: I think a little, yes. In a hierarchical company where there are two or three partners and a much larger mass of workers, everything that happens happens because it’s in the interest of three people, or two people, or one person. So if they aren’t interested in social questions, it’s very difficult for a worker to say, “Hey, I want to be more of a hippie.”

But at Lacol, there are 13 partners. We have roots in urban activism, so the team really has a mission of not harming society or the planet. And in my case, I have to listen to the voices and wishes of the other 12 members, and they, in turn, to mine. It’s easier to have debates among equals without anyone bossing everyone else around and ending a conversation by saying, “Yeah, that’s just not going to happen.”

I think that in this sense, the way we’ve organized the company does enable a more committed practice.

Sarah Wesseler: To follow up on this, I suspect this question came from a junior person in a firm where, as you said, a few partners probably make all the decisions. You started Lacol when you were students, and, as you were saying, you were participants in a certain kind of urban activism in Barcelona. So from quite early on, you decided not to enter the traditional firm structure where you would’ve probably been in a similar position as the person who asked this question: “How do I get my bosses to do socially meaningful work?”

Can you talk about why you decided to take this route instead of aiming for a more traditional architectural career path? How much of it was motivated by a pragmatic sense that there were enough opportunities to sustain an office in Barcelona with this kind of work?

Arrufat: I believe that we were never ambitious. Now, yes, we are businessmen and businesswomen. We have to create projects; we have to look for new work, to have a sufficient volume of business to maintain the workforce. We have to have flagship projects. We have differentiated lines of work. Now, yes.

But 13 years ago, when we started, we were very young. We didn’t have experience in anything. There was no work. You had to leave the country, and we didn’t want to. It was simply a resistance, no?

I think that the 2008 crisis broke everything, at least in the construction sector. There was already no work, but it broke the values, the discourse we’d been raised with—they all collapsed, at least for me.

So we realized that we didn’t want to leave, but we didn’t want to work in just any way. We didn’t want to spend seven years living precariously for someone else’s benefit until, you know, I can manage to have my little office by myself, or with a little partner.

We were very young. We didn’t have families, we didn’t have mortgages, we didn’t have big loads to carry . . . The initial investment was based on being able to live precariously without doing too much damage.

In this rupture of values, we started to organize ourselves. But we never saw, like, a window of opportunity one day—no. Simply, suddenly . . . well, our activity became known in the neighborhood. We learned from the neighborhood. The fact of being a cooperative came about because we’re in a very cooperativist neighborhood that understands self-employment and really encourages it.

And we came here with the idea of self-employment. It was like, “Well, hell, if it comes down to someone else paying me poorly, I would rather just pay myself poorly and deal with it.”

So we started there. And little by little, the people in the neighborhood started to call us. “Hey, I want to renovate my house.” “Hey, I want to do I-don’t-know-what.” “Hey, so . . . ”

In parallel to this work, which fed us and allowed us to learn—because we’re self-taught; we studied architecture in school, but almost none of us have been able to work for someone to learn the business . . . So in parallel to these jobs that gave us income and allowed us to learn, we had this neighborhood political laboratory that really allowed us to test what we never would’ve tested if the crisis hadn’t happened.

So we began to learn about housing cooperatives, about self-managed neighborhoods: people who were capable of satisfying their social needs without the state or companies to do it for them. It’s a neighborhood with a very anarchist heritage.

And I think it’s important to say that during the Spanish Civil War, Barcelona was 100 percent self-managed for two years. There was no municipal government; there was nothing. It was everyday people organized into assemblies and commissions and in streets and however they could. Like half the world, in the end—but yeah, this is less common in the West.

And that heritage hasn’t disappeared. During this time, political parties were born that are still active today. Unions born during this period are still active today.

And I think that the neighborhood, in some way, has steered all this toward “Let’s appropriate the means of production, of labor.” So here, the cooperative is the entity that satisfies this desire for self-employment, and also allows us to think bigger.

So now, yes, we have ambitions. I by myself—never in my life would I have been able to do what Lacol has done. But yes, us together, a few people—yes, we can develop a few different projects. We always use the same metaphor: One person alone can’t build a house, but ten people can build ten houses, and suddenly there’s an economy of scale. Suddenly you can become a little ambitious.

So I think that it comes from there—from a neighborhood that had responses to a profound global crisis, and from the fact that we were at the perfect age and left the university at this exact moment, and that we had the perfect need to look for these answers.

We know that without the financial crisis Lacol wouldn’t exist. We would’ve worked in other firms and stayed more or less in our professional structure, but I don’t think we would’ve done . . . Well, I hope so, but I don’t dare say it.

Botero: Very interesting that you frame it in terms of need: That if there hadn’t been the crisis, there wouldn’t have been the impulse . . .

Arrufat: I’d like to tell you, “No, I am super pure and super ethical,” but I don’t think that’s the case. I needed a catharsis, needed to see myself without a future, and needed to see that everything was wrong, and wanted to commit myself to what I thought was good—which surely is debatable. I’m speaking of my life; I’m not telling other people what to do.

Wesseler: Right, and it’s really interesting how your context influenced your trajectory. Particularly compared to New York, which is of course super capitalist.

Arrufat: I think it’s very tied to the local culture. For example, here people don’t always like the idea of philanthropy. And as far as I know—I’m not a great expert on New York or the United States of America, or even Latin America—but I know that these are places where yes, philanthropy exists; yes, it’s more developed. I think that here, as we experience it, it seems very paternalistic and very top-down, but I don’t know if this could be another way. So here, due to the lack of local reference points of people with purchasing power, and based on a vital need, and because we had local examples of working-class solutions—this combination allowed us to think about organizing ourselves this way.

I don’t know how it works in other places, but to me, it’s very tricky to say, “Yes, this is how it has to be. We all have to be members of cooperatives, and you just have to go along with it!” No. I only know that in my reality, in my culture, in my context, and with the crisis that came to us, today I defend this decision, and I stick with it, and I don’t want to do anything else.

In fact, if we had to close Lacol because we didn’t have any work, I don’t know what would come first for me: being a cooperativist or an architect. I mean, if I couldn’t find a job as an architect in a cooperative, maybe I’d quit architecture and open a pizzeria—I don’t know. Today I really like the way we’re organized, so I’d have to find myself in that situation to make that decision, right? But for now—knock on wood—it hasn’t happened.

But I can confirm that we really believe in what we’re doing, and that we’ve never had a time where we’ve said, “To hell with it! What if we change the organizational structure and become hierarchical?”

Botero: Do you do many projects outside of Barcelona? You have such an intimate relationship with the context that I wonder if you were offered a project abroad—or if this has already happened—how you would respond?

Arrufat: All our work happens within 300 kilometers of Barcelona.

And yes, we have tried a few times to collaborate with other firms in order to change scale. The practice is interested in growing in scale; we’ve never done anything larger than 40 units. But to do bigger things, at times you have to look a bit farther out.

So here we have a debate: If we go farther, how will it work? I won’t understand this cultural reality, and I won’t be able to apply important criteria with the same force that I can where I live. So I have to look for a local collaboration that can give me the same feedback I can get here.

And another issue with working at a distance is that we want to be sure that we’re not taking work from anyone else. And that we’re maintaining a critical spirit and being honest with ourselves, and knowing if we’re proposing something that makes sense from 2,000 kilometers away . . . Otherwise I’d rather go back to my cave and not leave, right? We’re sometimes afraid of arriving to another site and saying, “No, the solution to your problem is my solution to my problem.”

So I don’t know. It scares us, but it’s something we hope happens anyway.

Botero: Interesting. Well, we’ll have to check back in in five years to see how things have played out.

Let’s move on to a question from another audience member, Tim Keating. He’s questioning the climate mitigation potential of mass timber, citing studies he’s been involved in. Given the ongoing research into questions of sustainability, how do you evaluate the environmental strategies employed in your projects?

Arrufat: Well, we don’t do it alone. We work with sustainability consultants and with engineers. That’s to say, we don’t claim to know everything, and we’re not afraid to collaborate and build teams that are slightly larger so that we don’t say foolish things, right?

The statistic we use is that 50 percent of global emissions and global pollution come from the construction industry, from the creation of materials to the operation of homes: the gas used for boilers, the air conditioners, right? So that’s our starting point.

And advised by these teams, we try to ensure that our buildings have the least environmental impact at the lowest price. Which is tricky, because I imagine the same thing happens in New York as happens here: Sustainability is for those who have money. If you don’t have money, there’s no sustainability.

So fulfilling this criteria is tricky, and our benchmark is always to build with more respect for the planet than we would through traditional construction—with concrete and brick. So as long as we’re doing less damage than this, we feel more comfortable.

Although it’s true that with the current economic crisis of supply chain issues, of the war in Europe and its impact on energy supplies, of the global oil lobby and the end of the fossil era, material prices are going up at a very unsustainable rate. And sometimes we have to make decisions that aren’t sustainable because we have to choose between building housing and building nothing, right? So where do we stand? For survival and for the creation of dignified housing.

In this context, it’s important to talk about how to choose materials and what their impact will be, and this is very tied to prices and the economy. A cooperative of 40 units isn’t the same as a cooperative of six. The economy of scale, their ability to deal with energy improvements or material upgrades, is very different.

So in the end, it’s an intersection of many factors that lead to the decision. And above all, we don’t want the architects to be the ones making the decision. When it comes major decisions—those that relate to money—we do everything possible to empower the cooperative, and to make sure it makes the final decision.

La Borda isn’t made of wood because the architects chose for it to be made of wood: La Borda is made of wood because we, as the architects, dedicated a lot of time to educating the group so it could make an informed decision. The members were given a lot of information—comparisons of energy impacts, construction speed, construction waste—and then they said, “OK, let’s build it with wood.”

But in other projects, that hasn’t been the case. We have to accept the decisions of the group—although we are very upfront about what we believe does less damage to the planet.

Botero: The final question is if there’s something that you wish the audience would’ve asked, or if there’s anything we’ve spoken about that you think deserves particular emphasis or further clarification.

Arrufat: There are times when you’d like to talk about breaking this taboo: I think that culturally we’re very conditioned to employ or be employees. And those who have had access to knowledge about being an employer are maybe less afraid of creating their own company, and know more about how to take control of their lives. But for those who haven’t had this experience, the security of a salaried job is maybe a kind of aspiration for an entire lifestyle.

We [at Lacol] like to talk about alternatives. Not of one single alternative; I don’t think we ever claim to know the universal truth. I think we propose third ways. In general, [people are] very used to duality, to the binary. And I think [at Lacol], we’re very interested in working . . . I won’t say in a middle way, I’ll say in third ways.

I think it’s interesting even at the planetary level. One of the issues I think it’s important for housing cooperatives to embrace is degrowth. We all know that for 8 billion people to live in the same conditions of dignity, people in the West can’t live like they live now. We don’t have the planets it would take to satisfy this level of consumption for the entire population.

So yes, I think that talking about coming together, forming cooperatives, designing differently so that the cooperative can be a node that is as autonomous as possible in terms of energy, at the level of production . . . businesses that aren’t based on profit, or on a socially extractive economy. I think this gives us clues. Maybe it’s not the whole truth—I’m no genius. But I think it gives us clues toward paths that can help us arrive at a degrowth that brings us to a more sustainable place.

And, well, I’d say that I think that cooperativism, right now, both for housing and work, allows us to explore paths that are about to open up. And I think they’re along the lines of what we might need at a massive level, worldwide.

That’s how I see it. It might also be that I’m very naive [laughs], but that’s how I see it.

At the level of architecture, I think it’s good to talk about what it means to work this way. Regardless of what I earn, how I organize myself, whether I’m doing good or doing something bad, whether my impact is better or worse—as an architect it’s very interesting, because I’m able to carry out research. I’m able to hear the needs of collectives firsthand. And with my team, and with our collaborators, we can really try to respond to these needs.

The thing that architects tell us as soon as we start our careers—“We have to respond to social needs!”—I’m not sure if it’s true. But at least, yes, I’m trying to give answers to small groups of people that are asking me questions directly. So I feel privileged to produce an architecture that’s a little freer and a little more engaged with the end user. And for me that’s gratifying.

Interview translated from Spanish, edited, and condensed.

Explore

Peter Barber: 100 Mile City and Other Stories

The British architect presents his innovative housing projects and speculative urban designs.

Housing, Food, Air, and Water

Rural Studio's Andrew Freear and Rusty Smith discuss their work with the League's Rosalie Genevro.

Anna Heringer: Sustainability=Beauty

The German architect speaks about her love of mud as a building material.