The Abortion Clinic Next Door

Through research and design, Lori A. Brown emphasizes the ties between women’s reproductive decisions and broader social forces.

July 7, 2021

Site plan of proposed Alabama Women’s Center for Reproductive Alternatives. Credit: Lori A. Brown

By Sarah Wesseler

When architect Lori A. Brown began working on the design of an abortion clinic in Huntsville, Alabama, her client repeatedly emphasized one particular goal for the project: to be a good neighbor in its mixed-zoning neighborhood, which included houses and a new high school building. “He was really insistent that he wanted this to be respectful, wanted it to engage the community, be something that the community would not see as an eyesore,” she said.

In a nation where abortion has long been a political and cultural flash point, making clinics attractive for the benefit of neighbors may seem like a minor concern. But viewed in light of Brown’s investigations into the spatial logic of reproductive healthcare in the United States, the impulse is easier to understand. There’s a strong case to be made that abortion itself is a reflection of powerful forces at work in American society, and that the physical design of clinics should acknowledge these deep ties to everyday life.

Agency, abortion, and architecture

To illustrate the spatial dynamics of abortion in the United States, Brown often points to video captured during a 2012 protest outside a Louisville, Kentucky, clinic. In the clip, protesters line up on the sidewalk as escorts walk a patient to the clinic door, with one agitator loudly proclaiming that over 90 percent of women who end pregnancies “are doing it out of convenience.”

American debates over abortion typically foreground the choices of individual women, either to castigate them or to emphasize self-determination. But as Brown has painstakingly documented, women often have fewer options than others assume when it comes to childbearing. In much of the country, powerful social, legal, and economic pressures put them at high risk of unwanted pregnancy, then leave them with few resources to care for children once they are born.

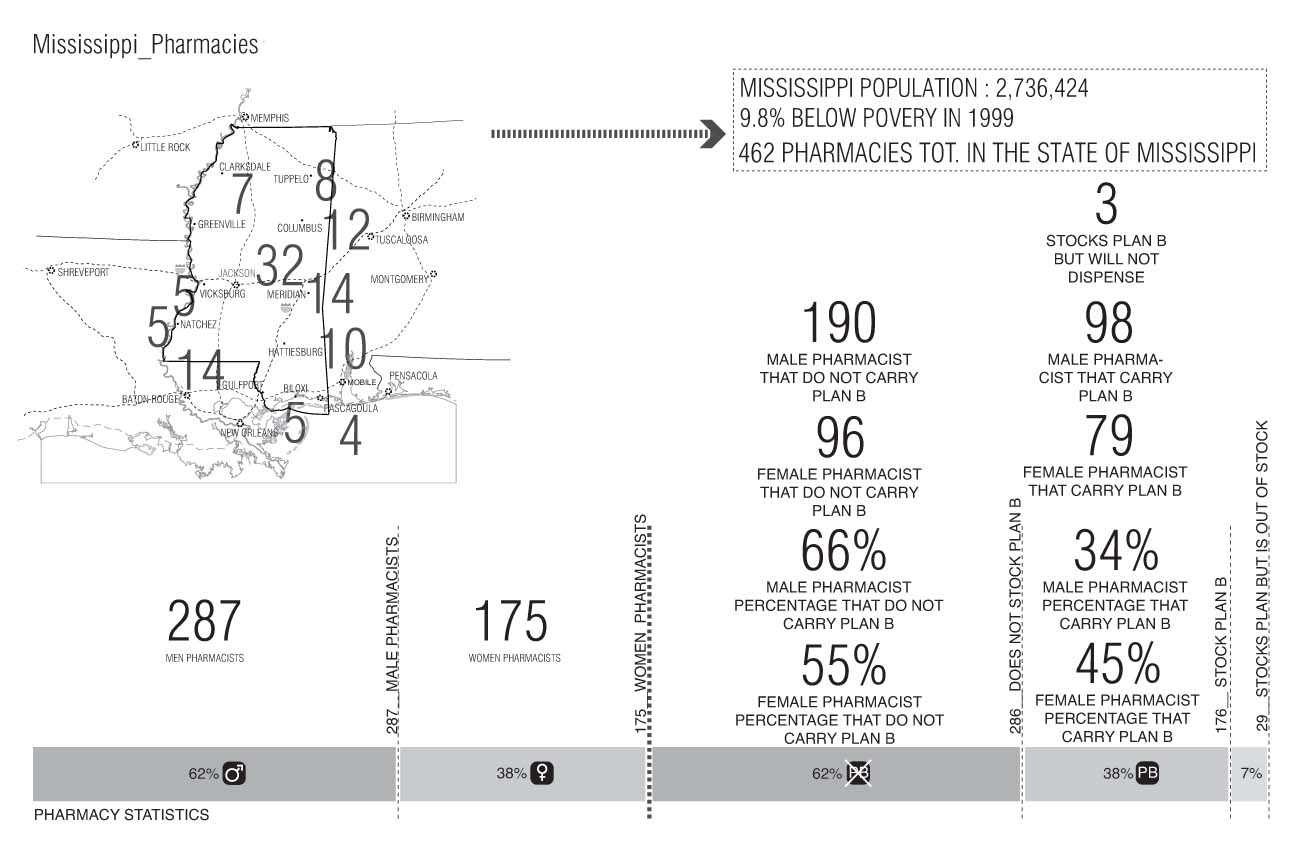

In preparation for her 2013 book Contested Space: Abortion Clinics, Women’s Shelters and Hospitals, Brown examined reproductive health dynamics in Mississippi, which at that time had the nation’s second-highest rates of teen pregnancy and gonorrhea. But despite the clear need for preventative measures to reduce these statistics, state policies prevent schoolchildren from receiving sex education unless their parents opt into the program—an outcome far from certain in the conservative region.

In the absence of parental permission, teens are placed into an educational track called Abstinence Only. But even the more liberal track, Abstinence Plus, has considerable drawbacks, including strict prohibitions on demonstrations of how to actually use condoms and other contraceptives.

Further increasing the risk of unwanted pregnancies, local pharmacists frequently refuse to distribute emergency contraception, Brown and her team found. Calling pharmacies around the state pretending to be women interested in buying the medication, they were repeatedly told that while it was in stock, staff members wouldn’t dispense it. Some pharmacists lied rather than refuse their requests outright, saying that they no longer sold drugs or that they couldn’t find the non-prescription kind. (Since no such drug existed at this time, this wasn’t a surprise to the research team.)

Due to these and other structural failures, single mothers of young children in the state—one of the groups most likely to seek abortion—experience exceptionally high poverty rates. At the time of the book’s publication, this figure was 53.5 percent for Jackson, Mississippi, compared to an average of 9.8 percent in Mississippi and 11.8 percent in the nation as a whole.

The case of Mississippi is extreme but hardly unique, particularly in the Bible Belt. Deprived of the information and resources needed to make proactive decisions about when and how to have children, many women here and in other parts of the nation face limited options. In stark contrast to the “convenience” narrative, those who opt for abortions often face extremely difficult decisions that have profound implications for their ability to support themselves and their existing children.

But policymakers and pharmacists aren’t the only ones failing women, Brown found. In her research, architects were all but absent from the picture, leaving often-hostile political and cultural forces to determine the spatial logic of reproductive healthcare.

Form, not just function

Hoping to begin correcting this imbalance, Brown has worked on the design of two abortion clinics. One, the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, is the last such facility remaining in Mississippi. To protect patients and staff from protestors who frequently congregate outside, the clinic had covered its fence with a black tarp. With the aim of creating a more welcoming, attractive environment, Brown co-organized (with Kimberly Tate and ArchiteXX) a call for design proposals, along with an exhibition of the submissions and related event programming, both at The New School.

Private Choices, Public Spaces, a 2014 exhibition and event series at Parsons School of Design. Courtesy ArchiteXX. Credit: Ashley Simone

This project led to an introduction to the director of the Alabama Women’s Center for Reproductive Alternatives, which had purchased an existing medical center in anticipation of new state legislation forcing abortion facilities to meet standards for ambulatory surgical centers. Known as a Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers [TRAP] law, this tactic is frequently used by conservative state governments seeking legal means to make the operation of abortion clinics prohibitively difficult. If this legislation were passed in Alabama, the organization’s current space would need to be closed and renovated, a time-consuming and expensive undertaking; buying a space already outfitted for ambulatory care was one way to avoid this outcome.

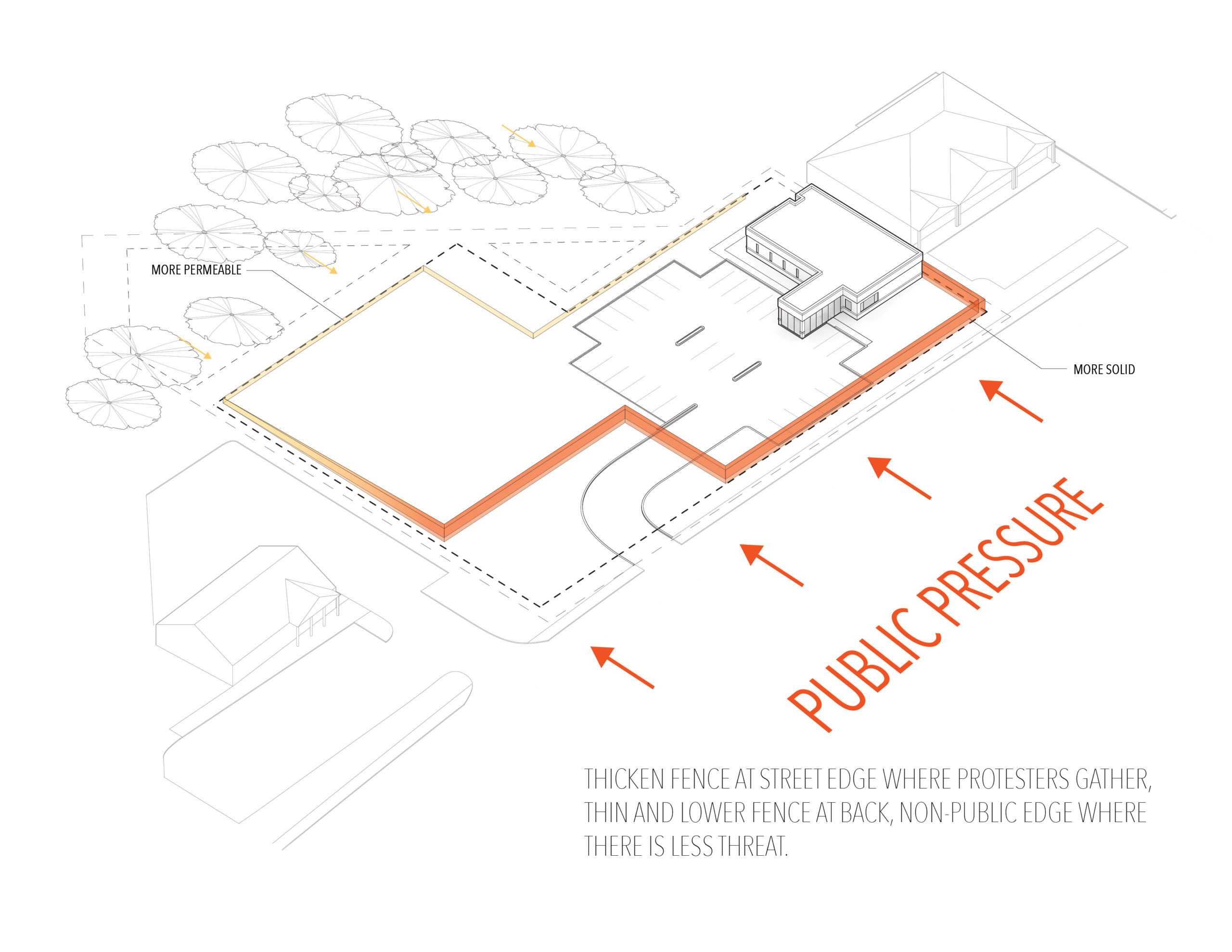

When Brown first began speaking with the clinic’s director, he, like the Jackson Women’s Health Organization, was most interested in hearing her ideas for the site perimeter. He was particularly excited about the possibility of incorporating a sprinkler system into the fence, having seen another clinic use water both to support attractive landscaping and to discourage protesters from coming too close.

Rendering of fence with embedded sprinklers and exploded axonometric drawing of proposed design. Credit: Lori A. Brown

In response, Brown and her assistant Patricia Cafferky proposed a barrier wall whose composite slats were enhanced by an embedded irrigation system near designated protest zones. Additional benefits of including a thick wall and landscaping on both sides: The mass and vegetation would help dull protest noise coming from the sidewalk—a common complaint among clinic staff and visitors—and create a lush and green parking area.

As Brown spent more time visiting the site and talking to project stakeholders, her scope grew to include a comprehensive rethinking of the facility’s site. In keeping with the director’s desire to be a positive addition to the local neighborhood, she studied nearby buildings and identified ways to echo elements of their design. In her finished drawings, the stone and rock used on the high school have been translated into gabion walls that define the site perimeter at the street edge.

Another design move that benefited both the clinic and those around it involved moving the driveway further from the medical building. Because protesters are legally required to stand in designated zones near the facility’s entrance, this would push them further from the structure, providing greater security and reducing noise for those inside. But the driveway reconfiguration was also designed to reduce congestion on the street, benefiting all who use it.

Site plan and rendering showing proposed new entry and dedicated protest zone. Credit: Lori A. Brown

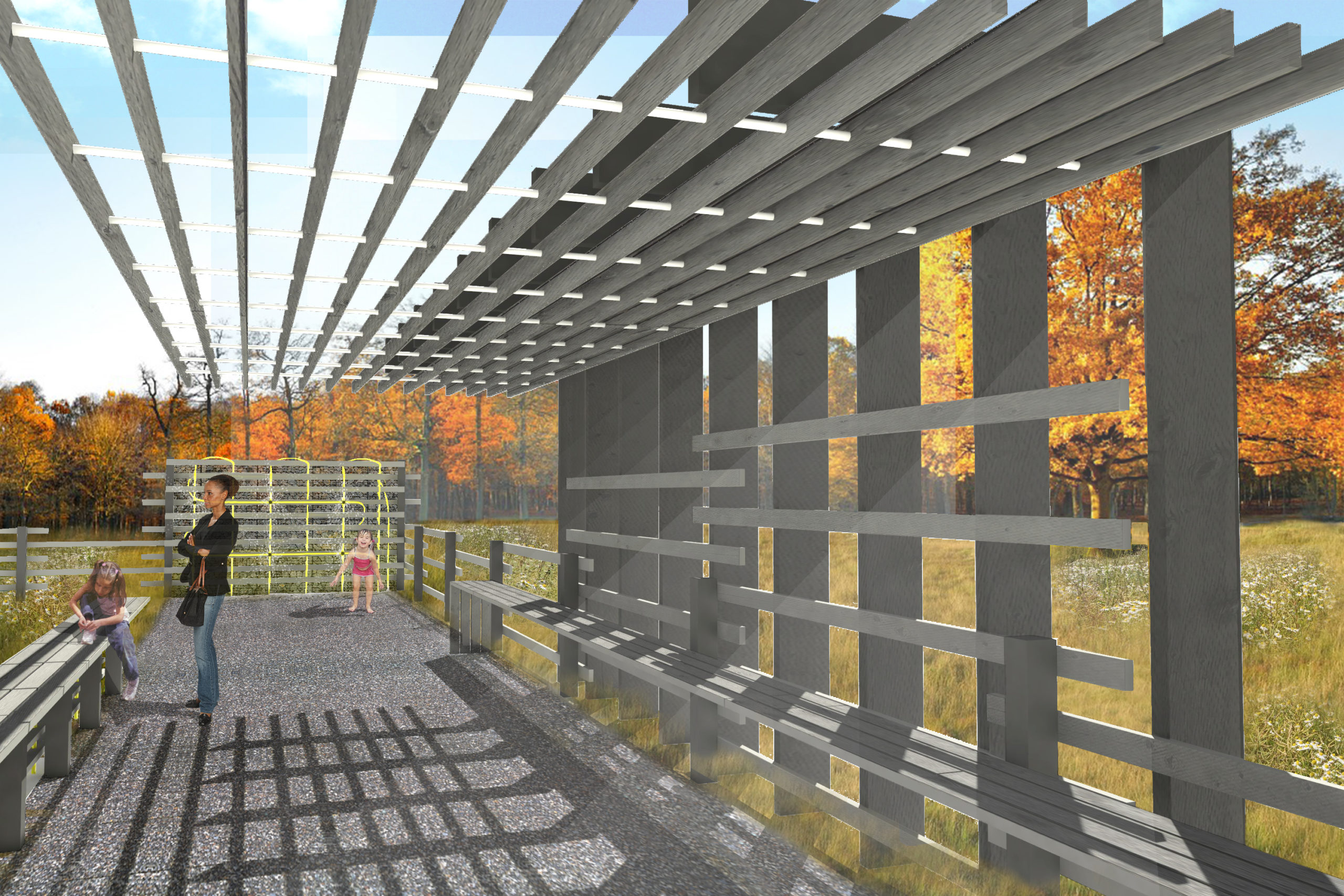

Several design changes reflected the need for spaces serving the community of the clinic itself. Interviews with staff members and volunteers revealed a need for a protected outdoor play area where patients’ children could wait during appointments, since legal requirements prevented them from staying inside the clinic. At the same time, workers needed a pleasant place to take breaks during the day or wait for patients to arrive—and preferably one that offered relief from the hot Alabama sun. To address these goals, Brown and Cafferky set aside a portion of the clinic’s property for a trellis with shaded benches, as well as a play area with a water feature.

The project remains unbuilt, with progress further delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic. But Brown is hopeful that the clinic will one day be realized, although further legal hurdles may arise. “I think it’s going to be a long, protracted affair—but one that they’re committed to, and I am as well,” she said.

Explore

A conversation with Susana Torre

An interview with Susana Torre, who organized a 1977 exhibition about female architects.

Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective

A 1977 exhibition showcased the range and quality of women’s work in the fields of architecture, planning, and design.

Inventing f-architecture

Dissatisfied with conventional models of architectural practice, the designers behind the feminist collaborative created their own.