Interview: Rael San Fratello

Emerging Voices 2014

Rael San Fratello

Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello

Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello, principals of the Oakland firm Rael San Fratello, shy away from working within a set philosophy, trying “not to define, but rather to constantly redefine ourselves.” Their diverse collection of work ranges from full-scale projects—such as the Museum of Nowhere in Antonito, Colorado; The Mud House in Marfa, Texas; and the art installation Prada Marfa—to folly-like experimental structures such as Saltygloo, a semi-structured shell comprised of 336 3D-printed panels made of salt harvested from the San Francisco Bay supported on lightweight aluminum rods; and Sukkah of the Signs, a.k.a. the Homeless House, built for the Sukkah City competition. Throughout, they aim to discover overlooked places and strive to “do the most with the least.” In March 2014, on the occasion of their Emerging Voices lecture (video embedded below, also available here), Rael and San Fratello sat down with League Program Director Anne Rieselbach to discuss their practice.

Anne Rieselbach: This series emphasizes the voice of practitioners. How would you describe your voice?

Ronald Rael: We’re still finding our voice, and we’re looking for our voice by speaking through architecture. There have been several times in our career where we told ourselves, “We need to figure out how to do this,” but we’ve discovered that we’re just too interested in the world to limit ourselves to any particular topic of research. That has sometimes been a difficult position for us because academic institutions want to see “a consistent line of research.” But we’ve found that we’d rather be enjoying ourselves through architecture—if that means at one point we’re 3D printing and at another we’re interested in stacking straw bales, then we’re going to take that route.

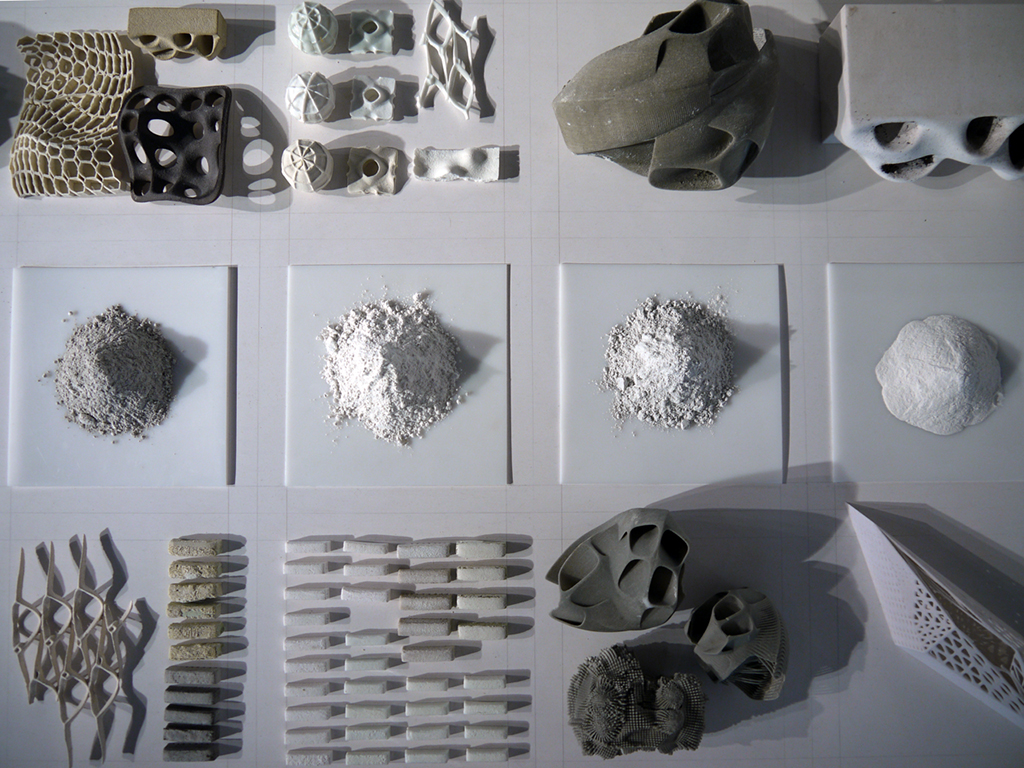

Materials for 3D Printing | photo: Rael San Fratello

Virginia San Fratello: Because our work is diverse, it’s not so easy for people who are looking in from the outside to tie all the projects together and see a connected stream of consciousness, if you will. In reflecting on our work though, we’ve realized that one thing we do consistently is we intervene in existing systems. So whether we’re looking at something quite large, like the Bay Bridge in California, or the border fence between the United States and Mexico, or something quite small, like the 3D printing machine, we’re always thinking about how we can interrupt or subvert this problematic infrastructure or technology. That seems to be a common thread that emerges frequently within our work.

Rieselbach: As an emerging firm, what do you see as the advantages and challenges to practicing in today’s economic, professional, intellectual climate?

San Fratello: There’s not a lot of paid work. Being out on our own, not having traditional clients or commissions, is very different than working in a more established professional practice. We’re inventing our own projects, and those take us on wonderful journeys.

Rael: We hit our head against the problem of architecture for many years. When we came out of school in the late 1990s, trained in these technologies that we were promised would change the profession, we were confronted with the reality that at that point not many firms were actually using digital equipment because it was expensive and inaccessible. But we wanted to participate in that world, and we decided we would just try to figure out some way to get there. It’s resulted in a really fun time for us, but also allowed us to be much more robust and flexible. We don’t really have to practice architecture with a capital “A,” we can say sometimes we’re designing buildings, sometimes we’re experimenting with materials, sometimes we’re writing books…

Museum of Nowhere Exterior | photo: Rael San Fratello | Click for a project slideshow

Rieselbach: What inspires the self-generated projects, such as NOWHERE—which struck me as a huge commitment of both time and money—or the various manifestations of the Border Wall project?

San Fratello: NOWHERE was inspired by a building—this old pharmacy in the very small town of Antonito, Colorado, where Ron is from. In a century of urban migration, there are about 700 people left in this town. The store had been for sale for many years. It’s a beautiful old building. We decided to buy it and renovate it into a gallery space that we would rent.

Rael: We wanted to see if it was possible to plant a seed of something in the town. Because this is not the kind of place that is vulnerable to the gentrification that completely transformed SoHo from artist lofts into high-end fashion stores, we were curious if you could just plant a seed of art and culture in a place and see if it grows to benefit the town.

Our first move was to call up every artist in the Yellow Pages to see if they wanted to rent it. We had one or two people interested, but then nothing happened for years. And we were paying a mortgage on the place, as well as paying taxes, and insurance, and making physical improvements to the building. Finally we just said, well, we have a lot of well-known artist friends. Can we just call them up and ask them if they will lend us their work to exhibit? So that’s how we ended up with work from Elmgreen & Dragset, Ehren Tool, Stephanie Syjuco, and Futurefarmers. Something started rolling there, and it was exciting and fun.

San Fratello: Eventually a woman previously with the Calder Foundation found us. She ran NOWHERE as an institution for a while, having live performances and exhibitions there, giving tours, and so on. But one day this guy drove up, pulled out a check with our names on it, and said, “I want to buy your building and open a drug store.” It turns out he ran a chain of drug stores in Las Vegas, his father was from a nearby town, and he wanted to provide a service for the area.

Rael: So, it’s exactly what we wanted, in a way—to plant a seed that would grow to contribute to the community. But, it was really bittersweet, because after all of the trials and tribulations of getting this thing going, all of a sudden it came to an end. We still have the sign though, and now we’re looking for a new somewhere for NOWHERE.

reThink Bay Bridge | photo: Rael San Fratello

Rieselbach: You have said that in order to take part in the creation of architecture, you often have to create disruptive situations that bring attention to your work. What do you mean by that?

Rael: We were working very hard for a very long time. And there was a point where we realized that much of our work, cancelled commissions, speculative projects, unsuccessful competitions, only exists on our hard drives. It wasn’t even printed—it didn’t exist anywhere, really. And if our hard drive crashed, then that was the end of our creative existence. So we started to think about how we could be much more speculative, particularly on projects that explored cultural transformation. The Bay Bridge project, for example, was maybe the really pivotal moment for us. We knew they were going to knock down the eastern span just to replace it with a new one for seven billion dollars, so we wanted to ask, “couldn’t this be a park?” We spent two weeks just doing drawings. Speculating. We’re not asking questions about aesthetics or budgets, we were asking questions about historical, cultural, and political relationships.

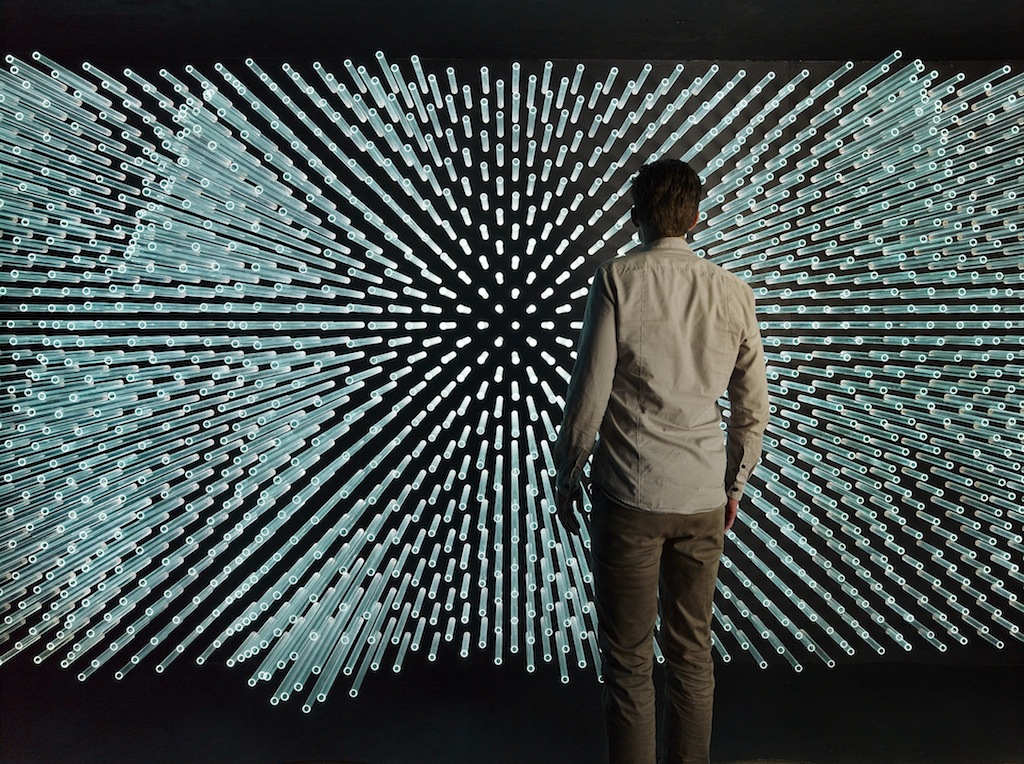

San Fratello: SOL Grotto is another good example. We created an installation for the Berkeley Botanical Garden out of salvaged glass rods from the Solyndra debacle and used their reflective qualities to create a sensorial space that connects you to the immediate context and the political history of the material, which was otherwise destined for the landfill. We felt like, if you just make one tiny little diversion, you can disrupt that flow of material, and the way people are thinking.

Rieselbach: A number of your projects incorporate repurposed elements that seem to serve a dual purpose: they both define form, while at the same time conveying a social message. How does repurposing inform your design process?

San Fratello: All the materials we use have a backstory. And it’s important to know where they come from, what their histories are—their provenance. That informs a larger story, a larger discourse around the project, because then the project becomes impactful not just for the physical architecture, but for all the conversations that emerge around it. The material becomes something much, much larger than itself.

Sukkah of the Signs | photo: Rael San Fratello

Rael: Our Sukkah of the Signs project is a good example. Before we were selected to participate in Sukkah City, we were already collecting handmade signs created by homeless people because we thought they were beautiful and interesting. Because Sukkah City is a project intended to draw attention to the historical structures built by people in the 40 years of wandering during the biblical story of Exodus, we felt there was a particular relevance for the sign as a building material in this project. We thought, wouldn’t all these signs purchased from homeless people all over the country provide a way of looking at the issue of contemporary homelessness?

Ultimately, the idea of creating a disruptive situation is about bringing, for a moment, a particular issue to light. Border Wall as Architecture is a project that basically tries to piggyback a social infrastructure onto a proposed and partially built security infrastructure. Between 2006 and today, the United States government constructed about 800 miles of a steel and concrete wall along the border with Mexico. As a security infrastructure, in our opinion, it is ineffective; it’s just a wall that people can climb over in five minutes. Homeland Security knows this well, yet we’re willing to put up a barrier that costs about three million dollars per mile. So we said, “Ok, how can we protest the wall through design, simultaneously revealing the ridiculous nature while introducing a possible design solution that improves conditions along the wall by solidifying the kinds of situations that are already bringing people together along the wall. For example, people were conducting bi-national yoga classes and having volleyball games over the fence, so we didn’t have to do a lot of design, we just kind of hyperbolized, and perhaps proposed the institutionalization of what was already happening there. What if you had a bi-national library? Or what if there were teeter-totters in a park that also has volleyball games? This is how we plug into a particular situation; expose the controversy while simultaneously trying to reveal the conundrums that exist. We hope our work reflects an understanding that the border wall is simultaneously tragic, ridiculous and an opportunity.

Border Wall as Architecture | photo: Rael San Fratello

Rieselbach: I’m struck by the polarity of your comment in the description of your practice: “We play in the mud. We start corporations.”

San Fratello: Emerging Objects really embodies that polarity. Emerging Objects is a creatively driven, full-service 3D printing agency we started in order to leverage our expertise in material development to help companies create compelling designs at unprecedented sizes that are unable to be achieved any other way. One of the first materials that we put in the printer when we hacked it was clay. It seemed like a natural step forward for us because we were already building with adobe. After maybe a year or so experimenting with clay, we started incorporating sand and dirt. It goes back to what Ron was saying, prior to Emerging Objects a lot of those ideas were in our computer and nobody knew about them. So we started a company and started putting them out there. It was a conscious decision not to be an architecture firm, but a tech company; we would be corporate executives, not Principals, and we would look to venture capital firms to get this thing off the ground.

Rael: The corporation would never have existed had we not been interested in dirt and mud. When we finally got a hold of a 3D printer through grants, we agreed that we were not going to be worried about breaking it with non-traditional uses. We’re experimenting with all kinds of materials—wood, paper, cement, rubber, and even bone.

San Fratello: And recently, salt! We wanted to make salt a project for a couple reasons: it’s a local material and very inexpensive. But also, Cargill, which owns all of the salt crystallizers in the South Bay, has set aside a lot of land where they want to build 12,000 houses for 30,000 people. So we said, well, why can’t salt be a material for these houses? The material is strong, waterproof and translucent, so we started thinking, could our corporation start to use salt as a seriously viable building material?

Saltygloo: 3D-printed salt structure | photo: Rael San Fratello

Rael: An international concrete company approached us to see if we could use some of their materials to 3D print a fairly large room structure. That’s happening right now—we haven’t finalized the design yet, but it’s supposed to fit within a three-meter cubic volume.

Rieselbach: You seem to be constantly redefining yourselves through making and the thrill of experimentation. Is it fair to say your design philosophy is more driven by material than form?

San Fratello: For us, that’s almost always the case. Even in the larger 3D-printed pieces, the form is often a function of how we can stack the material so it can be self-supporting. We’re inventing projects for ourselves, and right now those usually start with materials. I walk down the street and catch myself wondering if I could print a material, like carpet or mica or glass. There’s a great deal of excitement in materials.

Rael: Buckminster Fuller has a quote that’s always resonated with me, he said: “When I am working on a problem, I never think about beauty … but when I have finished, if the solution is not beautiful, I know it is wrong.” To me, that’s a really beautiful way of thinking about how we work.

Click any image to launch a slideshow with more images of Rael San Fratello’s work | Sol Grotto Interior | photo: Matthew Millman

•••

Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello, Rael San Fratello, Emerging Voices 2014, complete lecture video | Recorded March 13, 2014 | Running time: 50:22

•••

Both Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello earned their M.Arch. degrees from Columbia University. Rael is currently Associate Professor of architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, and San Fratello at San Jose State University. They have additionally taught at Clemson University and Southern California Institute of Architecture. They are past winners of the Metropolis Next Generation Competition, the Sukkah City International Design Competition, and received first place in the Van Alen Institute “Life at the Speed of Rail” competition. In 2013, the firm was the winner of both Design Lab: Next Nest competition sponsored by SITE Santa Fe and P3: People, Prosperity, and the Planet Competition sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency.