Playing Around in Mixed Reality

Leah Wulfman discusses collaborating with a child to design their installation Young Architects Project (YAP) and the opportunities of working with integrated physical and digital environments.

Leah Wulfman is a 2024 League Prize winner.

Traversing physical and digital realms, Leah Wulfman’s practice adapts the systems and logic of architecture and game forms for purposes of embodied physicality, play, and performance. For their League Prize installation, Young Architect’s Project (YAP), Wulfman worked with a five-year-old collaborator to create an immersive, imaginative, inflatable bounce house, challenging conventions of both professionalism and form.

This summer, the League’s Zoe Fruchter spoke with Wulfman as they prepared for the opening of the second phase of Young Architect’s Project at the Materials and Applications gallery in Los Angeles.

*

Zoe Fruchter: How did you conceive the installation concept for the Young Architects Project (YAP) in response to the theme of “Dirty?”

Leah Wulfman: I’ve wanted to do a project called “Young Architects Program” ever since I started working with children and young adults. From teaching youth programs, I knew that I wanted to extend architectural agency and architectural imagination to children, to open it up and really allow for more of a collaborative, even more contemporary, take on the way we think, work, and talk about architecture today.

When I was helping lead youth programs in Los Angeles, we took the students to The Underground Museum, which was an incredible, now-defunct museum set up by Noah and Karon Davis in 2012. It was wild to me how complex and deep the conversation got with the kids. You also see this in John Berger’s Ways of Seeing; when he engages children, they’re able to get the kernel of things in multidimensional ways quickly, with sensitivity and nuance. In many ways, decentering traditional perspectives and expertises in architecture is “dirtying” architecture to begin with, because we think of architecture, especially in the capital A, Western tradition, as something that you need specific schooling in order to practice and understand, and need to be an adult in order to have active agency in.

Fruchter: I’m curious to learn about your experience of working with Jin, the five year old you collaborated with on the drawings and designs for the exhibition. Specifically, how did you approach the dynamics of that relationship given your critical concerns?

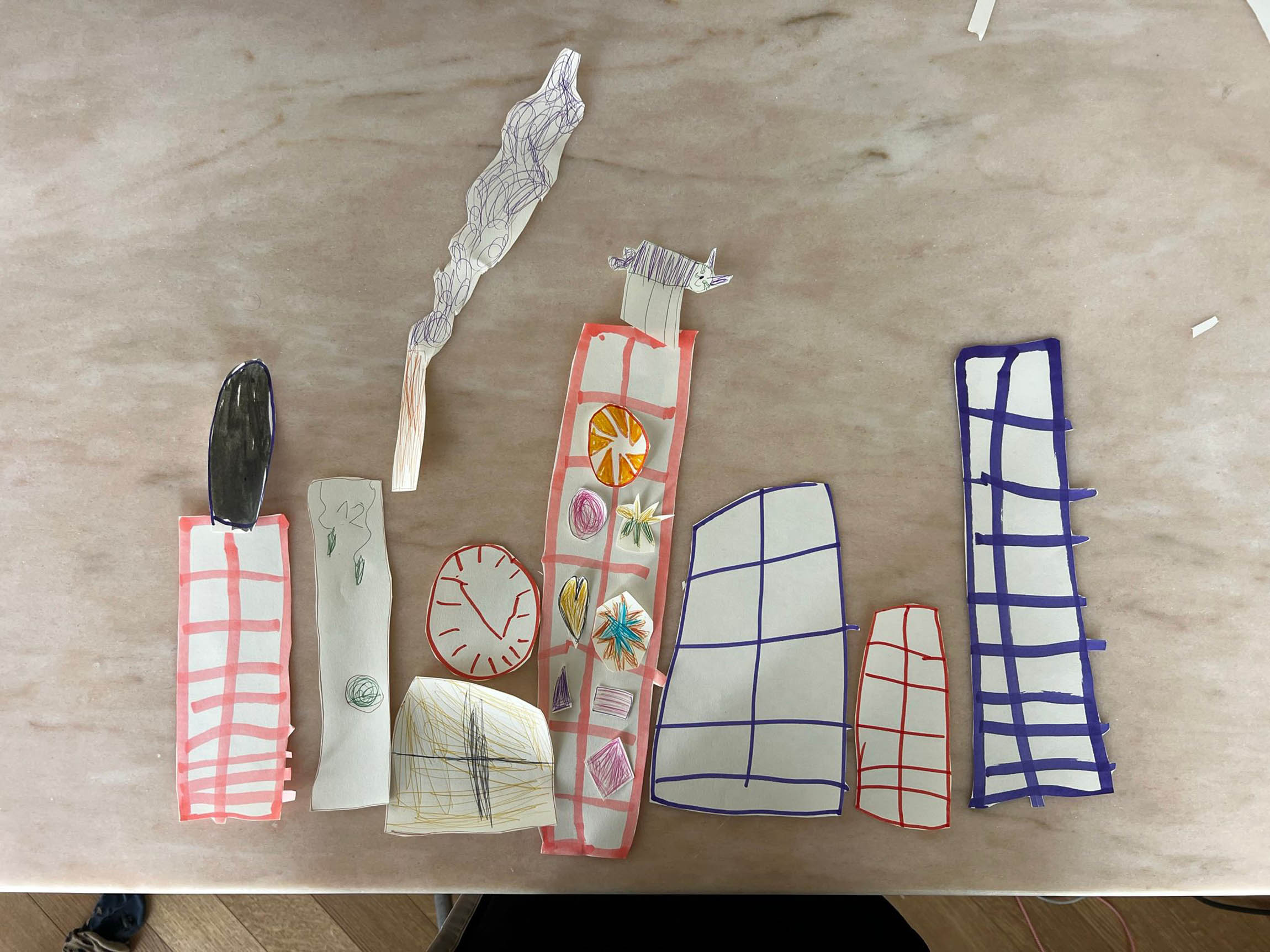

Wulfman: She’s an amazingly creative and purposeful person. We sent drawings back and forth and we had tasks for each other, almost like homework. I was talking to her, but I was also speaking with her parents who were sitting down and making space and time for her drawing sprees. And at one point, Jin started reciting descriptions; she would just speak them out loud, and then Florian [her parent] would transcribe them. And one of those verbal transcriptions is what ended up going into the final text for the exhibition.

So there’s the drawing aspect, which we can be free and interpretive about, but then there’s also the child’s imagination, which is exactly the aim and ask of what a Young Architects Program for actual young architects could be: Let’s reinterpret the built environment and fill in all the blanks of things we would like to see, the chimney that then starts to pop out balloons versus smoke. All those aspects came to the forefront, not only in her drawings, but also in the description where she talked about the way space transmuted: how one thing becomes another, becomes another, becomes another, which I thought was brilliant and speaks to how we all have agency to interpret and engage our built environment beyond the confines we are given.

Fruchter: Has she seen the installation, either online or in person?

Wulfman: I saw her in New York, and she was like, “Oh my God, did you bring the bounce house?” She’s really excited to get to the bounce house and see all her drawings activated in the space. She’s five years old, so she’s really exhilarated to have a show. In coming to Jin for the collaboration, I also remembered the first person that hung up my drawing, not on a fridge but an older artist friend who came to me when I was a young person and said: “Let’s talk about this drawing.” You return to that space and being able to allow for such an experience for someone else, it’s very special. I wanted to do that for Jin and would love to do that for more people.

During architecture school, I eventually became somewhat fed up with only ever talking about hypothetical projects as a practice of architecture. That’s actually a bit of how I got into VR and more computationally driven work, to bring forward an interactive experience versus having to talk about and perform architecture. I wanted people to enter and engage architecture without barriers. And of course, I had limited means of making that happen because I couldn’t outright finance and make a building, but in using virtual reality and real-time tools, tying architecture to an interactive experience, I was able to have an immediate conversation with anyone engaging the work. And not only anyone, I wanted a child to be able to engage my work and to be able to walk into the piece, the architecture, and then we could have a conversation about it, not just this overly conceptual description as the gateway to the thing but the thing itself. So all that builds into what comes into the show and the collaboration with Jin.

Fruchter: The political nature of your work is deeply embedded in the themes and methods but perhaps not immediately legible to the viewer or user. How do you think about the people who encounter your work – do you want to challenge specific ideas?

Wulfman: The aesthetics, the lens, and the materials are definitely political in nature and trans in practice. They’re intended to speak to certain audiences and certain types of being in the world. [The concept of] audience is also dynamic, in the way I see it. Even with my teaching, with any juror or critic that comes in as an audience, we must consider role play, positionality, bodies, formatting, and the power dynamics that exist within traditional critique. Actively, the work always implicates the audience and operates through mediation. So everyone is involved—whether that’s by the nature of the work being live-streamed, in-process, or interactive in a space or through remote means—it’s meant to allow for different experiences of space and time, different orientations towards those things that we think of as architecture. And then the fact that people can experience it despite different bodies, abilities, backgrounds, and within the different spaces that they might exist in, even different degrees of interest—the work is honed for those sorts of questions.

Fruchter: So much of your work is interactive, playable in a variety of ways. What’s it like to watch people engage with your projects? What do you learn from that aspect of the work?

Wulfman: It’s so special. I also love visiting buildings—I love architecture! My trajectory in working with video game engines and mixed reality is different from what you see in most of architecture academia and practice, since the digital and physical are nested to begin with. And as a physically embodied practice, [this work] pulls from the feeling of going into architecture, being absorbed with its details, reading buildings, and noticing how things meaningfully align or create discordant and playful wholes. And it’s amazing for me because, like I said in the beginning, wanting to work with buildings and immersive experiences and then be able to have conversations with people about it: I get that immediately, and I learn and gain so much from these conversations and reflections.

I think the coolest thing is how accessible mixed reality work can be and feel. My first full mixed reality project was CLOUD PLUS LABS, which was an immersive VR bathtub experience in which you travel through [virtual] spaces by making [physical] swim strokes: so if you do a breaststroke in a certain direction, you’re going to travel through the space in that direction. The movement was very intuitive, such that someone who is 80 and has never had been in VR as well as someone who is five years old can move around through a variety of spaces without inhibition. All my work tries to pick up different heights, scales, different points of access, and different ways of viewing, seeing, and experiencing. The best thing is that everyone experiences it all differently, but they can all access it. Yeah, so it’s a joy.

Fruchter: What’s next for you, for this installation, and for the Young Architects Project?

Wulfman: There’s the Materials and Applications show, then the project goes to Gameplayarts. Materials and Applications is a small space, which is neat because it forcibly shrinks to the scale of the child as it gets stuffed by the inflatable pieces. And then I figured out how to tie Unity Game Engine [a software framework used to create 2D, 3D, and interactive simulations] to trigger physical apparatuses, so, for instance, when something interacts and triggers something within the digital game portion, the bounce house blower can turn off and on and actively inflate and deflate the structure. And that interactivity is syncopated with a story and the description that Jin is telling, and her hand drawings become projection mapped onto the inflatable forms as part of this process of telling, mutating, reading, and re-reading the space. We’re having different activities that get hosted within the space that roll out these different aspects and allow participants to draw in and speak to their own architectural interpretations of the space and inflatable forms. I find this process incredibly rewarding, especially with going from the scaled-down physical models and prototypes that we produced for the [League] online exhibition and then immediately jumping in and starting to think through a multiplicity of scales and interactions.

I just wrote a chapter for a book on video games and architecture that goes through the history of mixed reality video games and architecture in relation to children’s toys, play-learning, and making. In the future, I actually really, really, really want to develop a series of mixed reality architectural applications and eventually start a company that operates at a wide variety of scales: the scale of the toy, then say the scale of the living room rug—where you would play a boardgame, a VR game, or a physical game like Twister—roomscale, the scale of the building, and then eventually—but it would be way far off—urban scale. If you talk to students about how and why they came into architecture, most often nowadays it’s because of experiences playing video games, most popularly Minecraft. But despite the influence of these games, I think there hasn’t been that key generational leap in the consideration of mediums and methods which takes us from Froebel Blocks and brings us to Minecraft. So, as architects, we are constantly working back and forth between the digital and the physical, yet we still have blank models on a podium and CG renders or drawings on a wall. I work towards locating that critical in-between as a meaningful space for play-learning, such that we begin to develop alternative working methods and tools for learning that simultaneously speak to and engage the hybrid spaces of today. That’s how we learn to play, make, and design for today and tomorrow, and not merely become end users.

Interview edited and condensed.