Very small or very large

David Eskenazi explores the links between scale and architectural values.

d.esk is a 2020 League Prize winner.

Los Angeles practice d.esk was founded by David Eskenazi in 2014. The Architectural League’s program director, Anne Rieselbach, spoke with him about his work.

*

Your League Prize competition portfolio focused on projects that explored graphic and physical representations of scale, which you described as “the means by which all architects bias one value over another.” Could you say more about this concept?

I’ve been thinking a lot about architects’ working methods and workspaces and how they might bias one value over another—materiality over social groups, for example. Scale is one aspect of this. As architects have transitioned from working through scale drawings to digital media, I think there have been losses as well as gains, but that at this point in history we don’t fully understand what those are. So this is something I’m interested in investigating.

Scale drawings force a sort of conceptual stop that prompts you to consider certain issues. For example, if you’re working on an eighth-scale plan, you might be thinking about the organization of space, whereas at the sixteenth-scale or 1:200 plan you might be thinking more about urban issues or landscape issues.

In digital media it’s a little bit different. We don’t have those kinds of stoppages. Everything is an infinite zoom.

Scale is just one factor that influences our values as a discipline, but it is important in that it tends to push you to value either materiality or economics. Maybe those are the extremes of architecture: something very small or something very large.

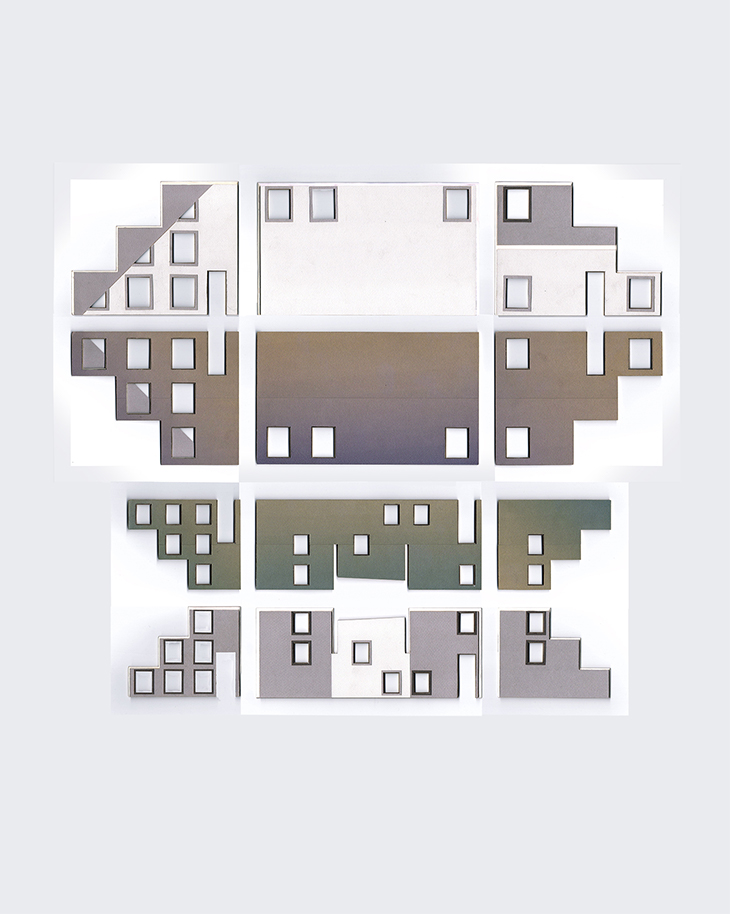

So in my work I’ve been using scale as a starting point. I take two things that are different sizes in the world and draw them at the same size, then compare the two and look at the value systems that are inherent in both sizes. It’s my way of commenting on how the digital world operates: In a digital model, everything can be big, everything can be small. You just make things bigger or smaller without much consideration. The work attempts to slow that process down and ask what consequences this might have.

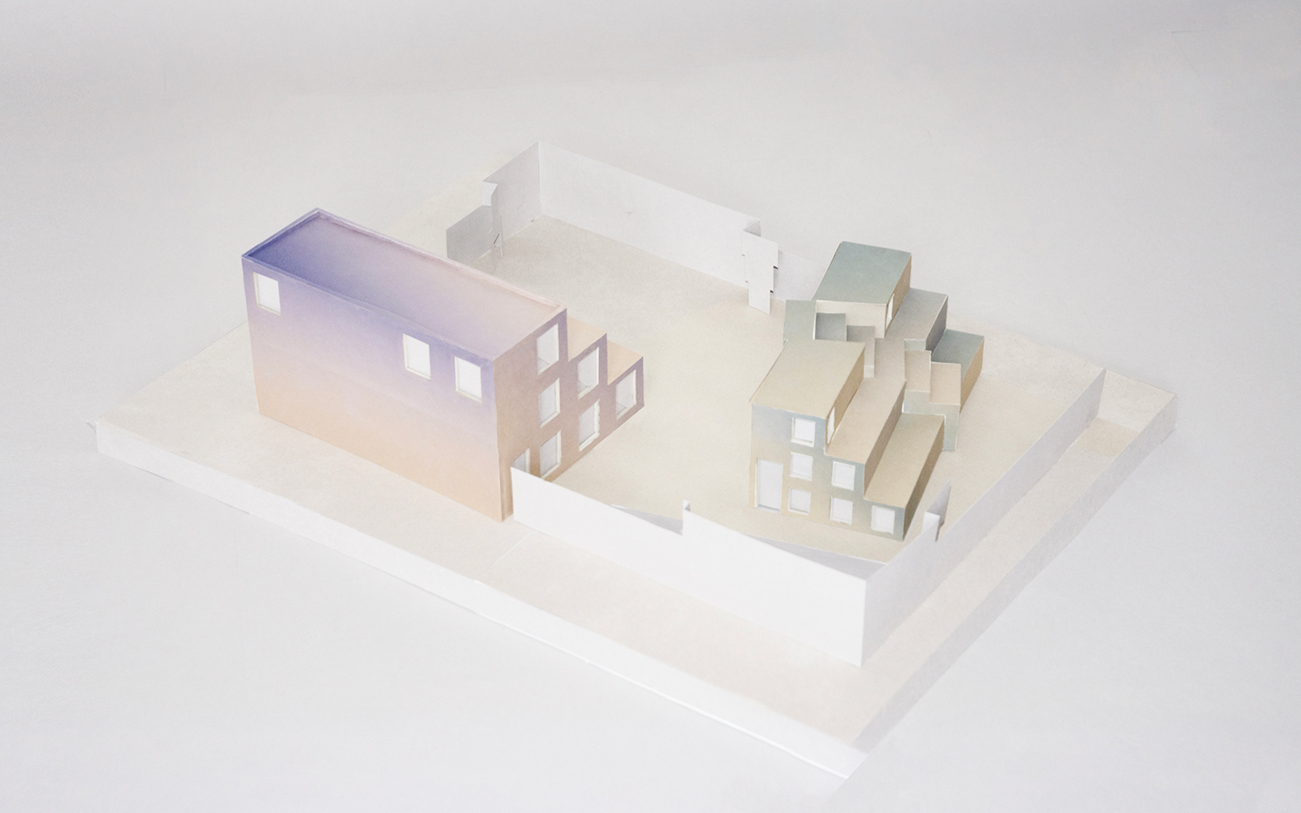

In Two Scrolls, for example, there are two models that are the same size, but that represent different scales. This lets you notice differences in materiality, in organization. So if one scroll is conceived as a 9-foot-high piece of architecture and another one as a 45-foot-high building, when we look at them at the same size we might notice that, in one, people are a lot bigger and there’s more information about window details and window mullions, whereas the other might have much more information about something quite different—how people organize themselves within it, for example.

You often work with paper to explore what you refer to as “scaled materiality.” Why this particular material?

It’s something I’ve been interested in since my graduate thesis, mostly because in the last ten years architects have been more excited about making really amazing models and drawings. But for even the most amazing drawings, when we move them out of the computer, we print them on paper. And models have traditionally been built out of paper. It’s all around us as architects. I think of it like a window: You don’t look at the paper, you look at the drawing on the paper.

That change in architecture mirrored a change I had been noticing more generally in the world. As newspapers were struggling, online retail took off. Paper suddenly went from something that was made into books and newspapers to something that performs much more structurally in packages. So the paper industry, which was kind of tenuous for a while, is still going quite strong.

More recently, I’ve been thinking about paper while reading Sara Ahmed’s new book about queering use. She talks about paper as the kind of thing that can be misused and still be thought of as doing what it naturally would do. The idea is that a lot of processes in the world are about papering things over, metaphorically speaking, by actually producing lots of papers—like bureaucracies producing paperwork to paper over their issues.

Also, paper has these funny histories in architecture. Plenty of architects have been interested in some of these questions before. I’m specifically thinking of the term “paper architecture,” which denotes a generation of architects whose work, at least for a time, was mostly unbuilt. Some of those architects put a lot of deep thought into their drawings and models, and I hope to build on that knowledge.

You’re currently working on your first full-scale building, Ziggurhut. How did these ideas about scale and materiality shape that project?

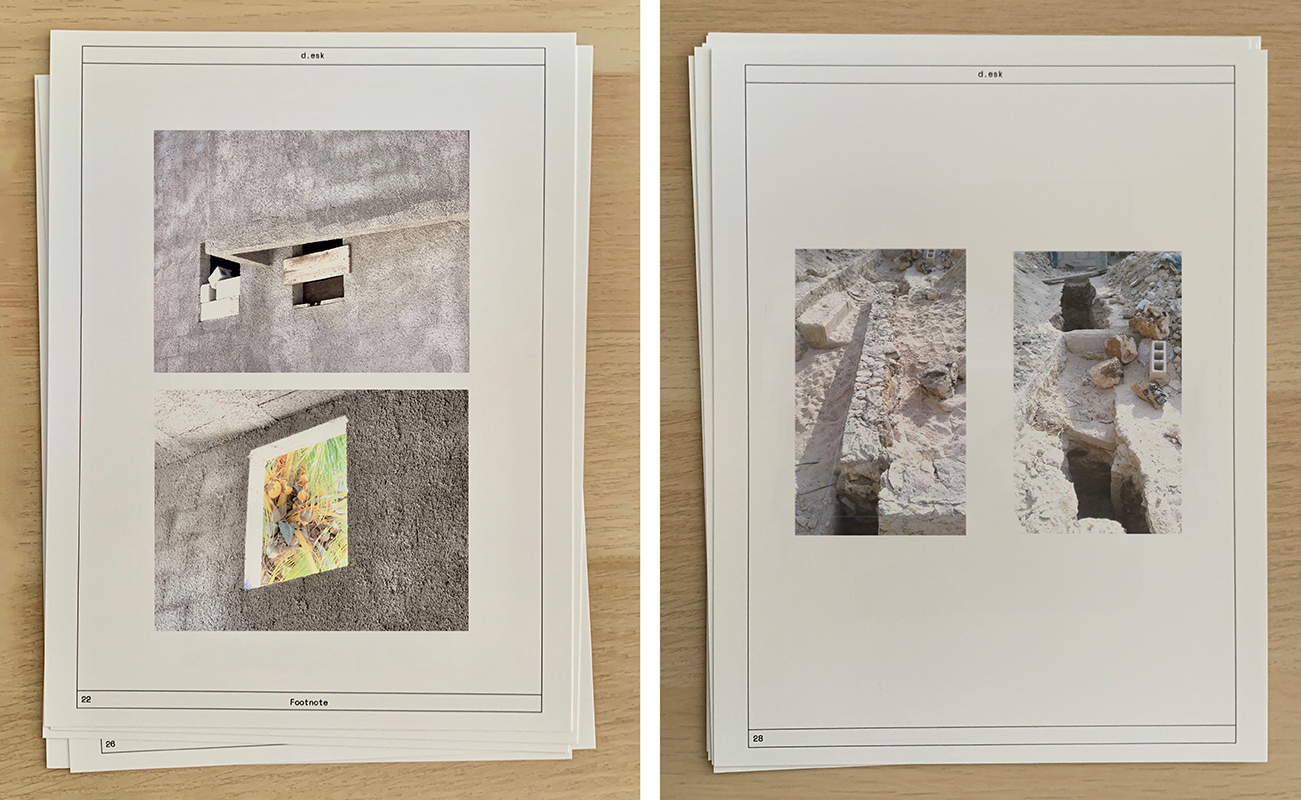

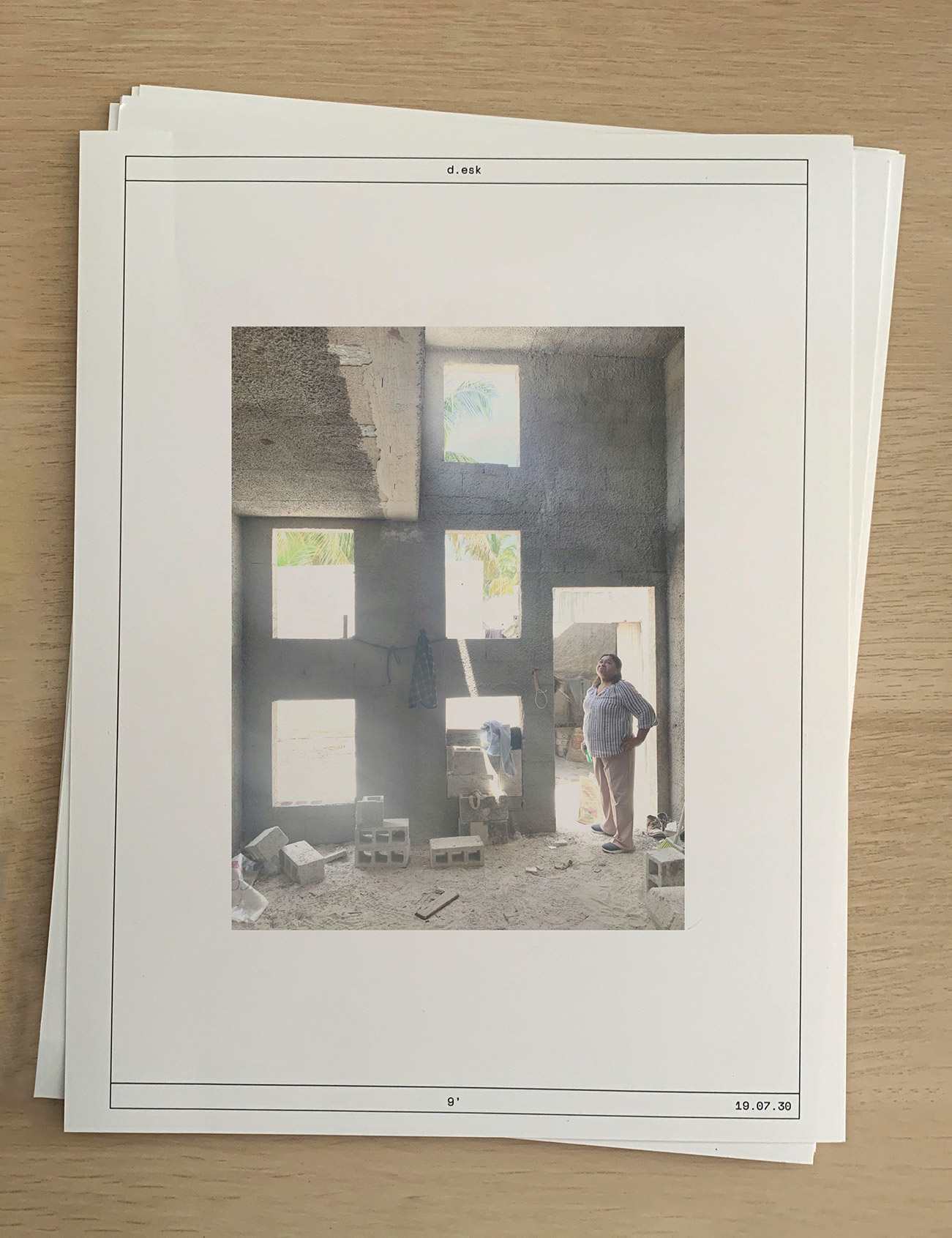

This project was not about paper at all, but instead was much more interested in the conditions of the site. It’s in Mexico, next to the ocean in the Yucatan. Most things in that area are built with super-solid, very straightforwardly constructed concrete masonry.

Part of the intention of the project was both to design a house for a family and to work within the limits of the economy of the area, the materiality of the area, how people traditionally build there.

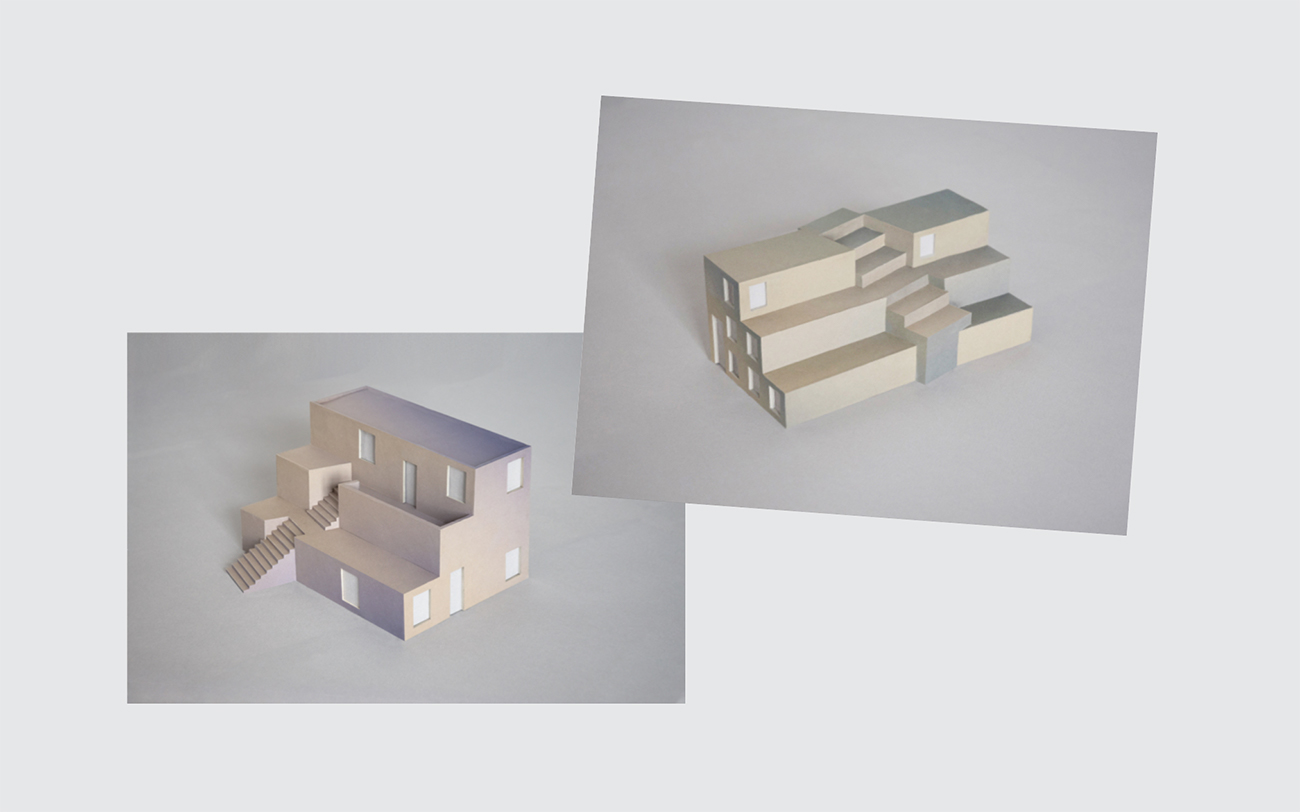

The Ziggurhut was conceived as two different houses, one that’s more of a guest house and one that’s a main house. The houses are two sizes of the same stepped form, and both are intersected by another stepping form at different sizes, one an actual staircase and the other an oversized staircase.

Certain things scale between the two houses, such as the form and the windows, and other things don’t, like the doors and other elements that are tied to human size.

As the construction workers have been building the house, they’ve have been doing all sorts of interesting things that I wasn’t expecting. I designed all the walls and windows to be dimensioned to the concrete masonry unit. But it turns out they don’t make it that way. They build the wall and then cut everything out of it afterwards, which is so amazing. It felt like a digital model: You build a solid form and you just poke stuff out.

If some of my other work has been about, “Oh, I’m a young architect, I’m interested in models and drawing, that’s what’s available to me,” this one has been much more about how construction methods change in different locations.

Building has stopped for now because of the pandemic, so the house seems actually quite abstract right now. It looks like it’s in the middle of construction, but also kind of like a ruin. You can see a lot of different things in terms of materiality. I know that the clients want to eventually paper over a lot of the roughness, cover it with stucco, etc. But I am hoping that we can finish it in a way that speaks to the process: the architect’s intention versus the contractor’s way of working—I admit, I had my own blind spots as to these local conventional methods—and how these conflicts actually play themselves out. I like the idea of working with that messy conflict. I think it speaks to larger issues between authorship and labor.

But when you have clients, you’re not the only one making decisions. Which is good. So we’ll see if that’s possible. Once we can all get on a flight down there again, we’ll start that discussion.

You recently revisited the outdoor space between the two Ziggurhut houses with your installation “Slump Model.” Could you talk about how this came about?

I was asked to do an installation at Woodbury University, and their gallery is called the Wedge Gallery because it’s literally wedge-shaped in plan. I love that naming convention, by the way. I really wanted to make a physical model of the Ziggurhut, and I thought that, rather than make both buildings, it would be interesting to make one model that took the form of the gallery—to take, let’s say, the size of the bigger house and the size of the smaller house and make a form that interpolates between the two.

So the installation begins with this form, and then it’s built out of paper only, with minimal attempt to maintain the geometry. So it slumps down and moves away from its ideal state into a kind of primal state, or a more base materiality. It sort of rests there—it’s a little slumpy, it’s a little bit low. It’s not upright and strong; it’s much more weak and tired in a way.

This was a year after the last election, and that was kind of how I was feeling. It seemed appropriate for the moment.

Did you learn anything about Ziggerhut while working on this installation?

While we were doing this installation, we were also working on design proposals for the courtyards at the Ziggurhut. The two were unrelated in many ways; we were trying to figure out, like, “Oh, they want to have a grill and a fireplace and a pool.” It was sort of funny to be basically exploring a disciplinary discussion at the same time. Disciplinary questions obviously come into play when you’re designing a house, but you’re also dealing with a place, a client, a contractor, etc.

The clients saw the installation and they loved it—and they were also so happy that that’s not what their house was like. I’m still working on finding a client that might want a house like that.

I think the jury’s still out in terms of exactly how the installation influences Ziggurhut, but it has definitely influenced other works since then, and probably will influence another house in the future.

Interview conducted on May 21, 2020.

Edited and condensed.

Explore

Michael Bierut: How to make architecture out of paper

Graphic designer Bierut discusses the challenge of representing architectural ideas in two dimensions.

Interview: SO – IL

An interview with SO – IL's Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu, as well as a lecture video and project slideshow.

Transversal modernity: Spatial discourse in architectural paper projects in Iran, 1960–1978

Shima Mohajeri examines a 1973 design proposal for a civic center in Tehran by Louis Kahn.