Renzo Piano: Background and mentors

Renzo Piano’s architecture is strikingly un-Italian. Concerned with lightness not gravitas, technology not typology, its predilections and forms are those of northern Europe and America. His work owes nothing to the Classicist and Rationalist strains of modern architecture, but rather to that which evolved out of Neo-Gothic and into the bio-technic and Functionalist streams that see equivalences between the organic and the mechanistic. This trend reached an obvious extreme with Art Nouveau. It found many forms of expression in the 1950s and some in the 60s. Now it continues to some degree in High-Tech, with its Vitalist concentration on structural and circulatory anatomy and on sensually sculpted components and joints. But in none of these is the relationship between the organic and the mechanistic explored in the rich variety of ways that it is by Piano.

Despite this un-Italian character, Piano’s architecture is also heavily influenced by his family and Genoese background. His father and grandfather, uncles and brother were all builders, and he grew up familiar with and fascinated by construction sites. A desperately shy boy, rather awed by his father, Piano set himself a private challenge to devise ways of making things equivalent to what his father built, but more economical in material and lighter in weight — and so perhaps less imposing on people and place. He grew up on the edge of Genoa with its introverted, claustrophobic old city of tall thick walled buildings and narrow streets. But to him it was the opposite dimension of Genoa that most appealed, the docks with the sleek ships and busy cranes and their promise of adventure on the open sea and in far-off lands. All these influences and interests are still so obviously present in the work of Piano and the Building Workshop as to need no further comment.

After study at the University of Florence and Polytechnic of Milan, graduating from the latter in 1964, Piano sought out a number of formidable mentors, some Italian, some not. Franco Albini, a product designer as well as architect of the Rinascente department stores and some distinguished historic restorations and conversions, had been his professor in his early years in Florence and became his first employer. From him Piano learned craft attitudes to material and detail, and about eliminating the unessential. In these early years Piano also met Jean Prouvé and later when building the Centre Pompidou they became close friends. But, for all the obvious similarities in their work and his admiration for the older man, Piano was not so much influenced by Prouvé as confirmed in his already formed interests and approach. Prouvé’s father, a founder of the School of Arts and Crafts in Nancy, had been very influenced by the writings of Ruskin and Morris. Though these were never explicitly discussed, Piano concedes that it is probable that conversation with Prouvé contributed to the affinities between his ideas and those of these writers and so furthered the Anglo-Saxon rather than Italian cast of his ideas and sensibilities.

In the academic year 1967-8, Piano was a teaching assistant in Milan to the architect and product designer Marco Zanuso. From him, and from the course they taught on the properties of materials, Piano honed his feeling for and understanding of materials. Shortly afterwards his interest in lightweight structures was intensified by meeting the British-based engineer Z.S. Makowski, who specialized in space frames. In Britain he also became aware of the Archigram group. Its various visions of technology enveloping and extending the body, and of nature enveloping technology, probably influenced Piano’s quest to bring technology and nature into happy harmony. Certainly Archigram’s playful spirit and carnivalesque celebration of crowds, tents and electronics continue in Piano’s work.

Piano with Louis Kahn circa 1969

In complete contrast to these other influences and mentors was Piano’s last employer, Louis Kahn, in whose Philadelphia studio he worked developing the design for the roof of the Olivetti factory. Piano says he took little architecturally from Kahn, but did learn the importance of creating the right conditions in which creativity could flower.

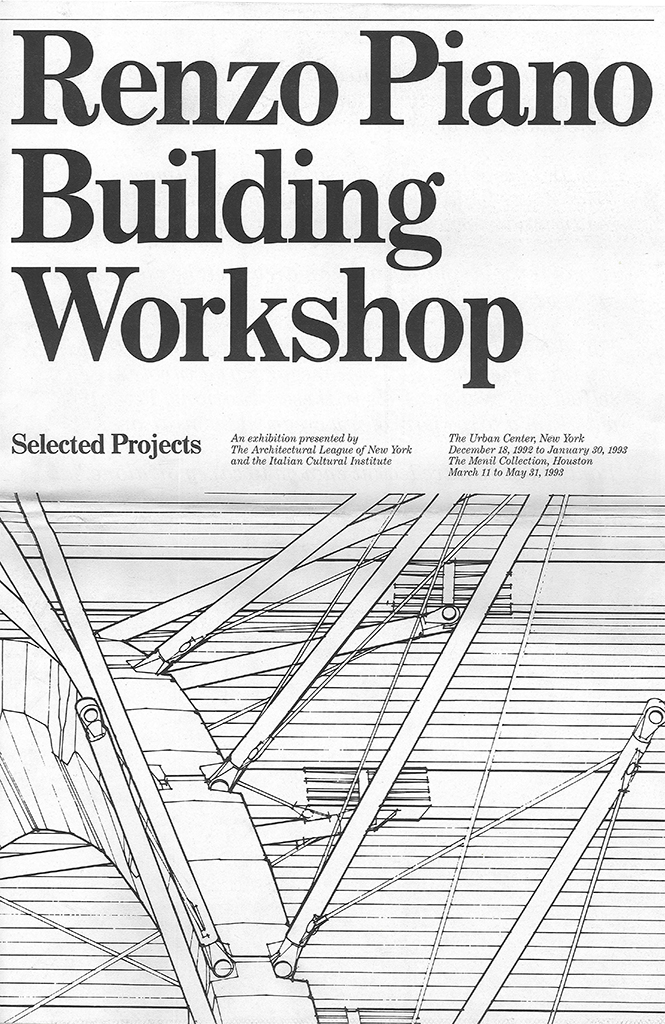

Studio Piano

Piano devoted himself almost entirely in his first practice, Studio Piano, to designing and making lightweight enclosures, experimenting particularly with plastics and tension structures. The engineer for these structures was Flavio Marano, who is still part of the Building Workshop, though now as the administrator. The builder was the architect’s late brother, Ermano Piano. Right from these beginnings Piano adopted his continuing commitment to design as a·form of research. But here he concentrated only on technique and some building components (though through these he also pursued aesthetic concerns with lightness and translucency) and so on only a very small part of architecture proper. Pursuing above all economy of means as well as lightness, these buildings were conceived of as ethereal and ephemeral. Most no longer exist. It is fitting that this period concluded with a temporary building, Piano’s most mature work yet. This was the Italian Industry Pavilion at the 1970 Osaka Expo, a building that anticipates British High-Tech’s continuing obsession with exposed suspension structures.

Piano & Rogers

The Osaka pavilion and Piano’s experiments with space frames and other lightweight structures brought him to the attention of not just Z.S. Makowski but also of Richard Rogers, who with his ex-partner Norman Foster was already becoming one of the two leaders of British High-Tech. Although born in England, Rogers is of Italian parentage and is also nephew of the major Italian architect Ernesto Rogers, and has always identified with Italy and kept abreast of developments there. Piano and Rogers formed a celebrated partnership that climaxed in their creating the building that was to catapult both of them, while still young men, to international prominence. The building is of course the Pompidou Center, that seemed to crystallize a large chunk of the Zeitgeist when selected as a competition winning scheme by a jury that included Jean Prouvé.

The Pompidou is such an extreme expression of the Modernist ideal of the building-as-machine, and building-as-kit-of-parts as to be almost a caricature — albeit a very cathartic one. A monument to both function and flexibility, it serves neither particularly well. And yet its provocations and promises seemed so liberating that it was immensely popular with the public and, for a while, influential with architects.

Yet no matter how forward-looking the Pompidou seemed at the time, in retrospect it can be seen as firmly rooted in Parisian history. Aerial views of Paris show that it has remarkable affinities with Notre Dame. Both loom larger than and isolated from neighboring buildings, and, in a similar pursuit of transparency, the length of both is rhythmically articulated by external structure. Now too the Pompidou Center’s affinities with Jean Prouvé’s (with Baudouin & Lods) Clichy Marché and Oskar Nitschke’s Maison du Publicité project are obvious and well-known. Keeping in mind also the Maison de Verre and Paul Nelson’s projects, not too great a stretch of the imagination is needed to see the Pompidou as latent and inevitable in Paris. Without the intervention of the Second World War something similar might have been built decades earlier. Now too we might see this sensitivity to place and tradition, as much as the concern with advanced building technology, as the pointer to Piano’s future direction as an architect. From now on he would prove that concerns with place and tradition and with technology need not be incompatible.

Building the Pompidou was important too for the experience of running and coordinating such a huge undertaking. Piano claims he learned both determination and professionalism coping with and coordinating the many client bodies, consultants and sub-contractors involved as well as the various teams of architects, each concentrating on a different aspect of the building. Young architects from around the world gravitated to Paris to take part in the “adventure in teamwork and international cooperation.” Thus came together the creative core of the future Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Peter Rice from Britain was the engineer in charge with Ove Arup & Partners and collaborated with Piano on nearly all his major projects since. Architects Shunji Ishida and Noriaki Okabe came from Japan (by way of London and Paris respectively). Bernard Plattner, who ran the site, came from Switzerland.

Piano & Rice Associates

After the arduous and onerous task of building the Pompidou, Piano felt the need to return to Italy (though he kept a small Paris office) and recharge himself. He formed a partnership with Peter Rice and together they embarked on an intensely experimental phase that lead to an enormous broadening of the concerns and approach that has shaped all subsequent work. Developing an experimental car for FIAT (the VSS experimental vehicle that influenced the new FIAT Tipo), they learned about industrial production and prototyping; making architectural history programs for television (“The Open Site”), they focused not just on Gothic cathedrals, but on the social cooperation, tools and assembly processes with which they were achieved; and in the Corciano housing and Otranto reconstruction projects they became involved in community participation and other social issues. From all these projects, but particularly the latter two, Piano says he learned the art of listening, of not just hearing but patiently understanding people, a skill essential to serving them rather than striving for fame and self-glorification.

Of these projects, it was that for Otranto in particular (which might in part have been inspired by insights gained in making the television programs) that has influenced other architects and perhaps most expanded and redefined Piano’s own approach to architecture. Yet the experience of working with the motor industry, that is far more advanced technically than the building industry, was immensely important too. This brought contact with materials such as ductile iron, used for the car chassis, and plastics such as polycarbonate, as well as with new glue technologies that could secure these plastics to other materials such as steel. Ductile iron was later used for the trusses of The Menil Collection, and the polycarbonate and glues on the IBM travelling pavilion.

Renzo Piano Building Workshop

After the dissolution of the partnership with Peter Rice in 1981 the Genoa office took the name Renzo Piano Building Workshop. (The French office only changed its name from Atelier de Paris somewhat later.) The name is virtually a statement of intent. Being in English makes explicit Piano’s un-parochial perspective and international ambitions. And Building, rather than architecture, together with Workshop, emphasize a pragmatic and experimental hands-on approach, and imply too that it is non-hierarchical and participatory.

With the taking of this new name, Piano’s architecture enters its mature phase. All the experiments and lessons of the previous phases are consolidated, as is the stable core of his multinational team of collaborators and consultants, in producing works that are more complex and complete than what went before. Yet the works are no more uniform or less experimental. Context in all its spatial and temporal, physical and cultural dimensions now heavily conditions design. And the commitment to start each design afresh remains. Materials, whether new or old, are explored for new potentials, and components are refined until they achieve some novel organic integrity. These factors ensure the striking freshness of each design and the extraordinary heterogeneity they exhibit collectively, as seen in this show.

The text below was originally published in the exhibition catalogue for the 1992 Architectural League exhibition Renzo Piano Building Workshop: Selected Projects. All text by Peter Buchanan, © The Architectural League of New York.

Next: Part 3: Projects: UNESCO reconstruction experiment & IBM traveling pavilion

Previous: Part 1: “Time and Place, Technology and Nature in the Work of The Renzo Piano Building Workshop”