Interview: Ben van Berkel

UNStudio cofounder Ben van Berkel speaks with the League's Gregory Wessner.

Ben van Berkel is co-founding partner with Caroline Bos of UNStudio, the international architectural practice based in Amsterdam. On the morning after his Current Work lecture at the Architectural League, Ben van Berkel sat down with Gregory Wessner, the League’s Digital Programs and Exhibitions Director, to talk about the firm’s process, the critical importance of infrastructure, and what he thought about being “SuperDutch.”

Gregory Wessner: You changed the name of the firm in 1998 from van Berkel & Bos to UNStudio, to emphasize the idea of “networks” in the firm’s process. The framing and understanding of “networks” has arguably evolved since the late 90s and I was wondering whether that was the case for the firm as well? Have your ideas about networks—what they are, how they work—changed since then? Has the nature of your collaborations changed, or the way the firm operates, changed over the years?

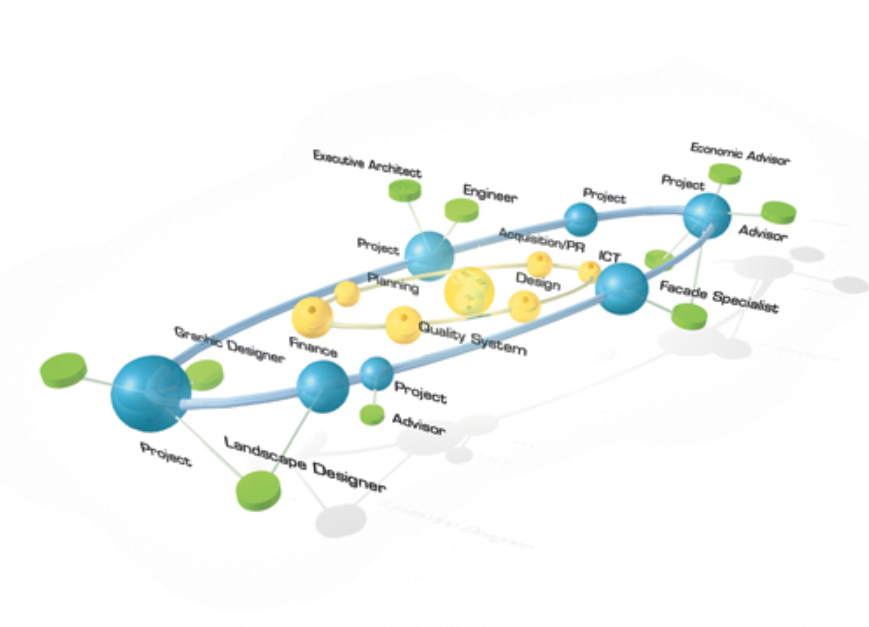

Ben van Berkel: It was interesting how we reorganized the studio in the late 90s because it was, in a way, based purely on speculative ambition. We recognized that we weren’t working in a linear manner anymore as there were no longer draughtsmen in the traditional sense, and the whole production of drawings was different. But it also had to do with the clients, as their approach had also changed. Clients no longer came alone to the table, but instead came accompanied by numerous specialists. So we began to work alongside these specialists and because of this we learned to work in a relational, rather than in a linear way. That was how the idea of the “united network” concept came about. Of course, what a lot of people don’t know is that UNStudio also stands for “un” studio—as in “not” a studio—so there is also the idea that the studio can be disintegrated and dispersed. But you’re right, by working as a network practice, we have now also learned how networks operate. You have to question who the actors are within the network and what role they play in the whole. Bruno Latour writes a lot about this, so we have learnt from him as well as from several other thinkers and philosophers, and of course just from practical experience. But perhaps the most interesting thing for me currently is in fact how you go about enriching a network through knowledge management. At UNStudio we now work with “knowledge platforms.” These internal research communities deal with all areas of design, from concept to construction, so if somebody is interested in the latest developments in scripting, or in specific new materials, then they can join the relevant knowledge platform to research and then share their findings. But this is not limited to within the practice, we also invite people from other professions, such as academics, engineers, etc., who then also exchange knowledge within the network.

Wessner: So where does the architect—where do you—fit into the network? Are you the master coordinator? Or are you just one node on this network that moves information and ideas around it?

van Berkel: I always need to learn to operate and work in different scales. And I need to do the same with regard to how I work with my network in the office. It’s very hard but I have learnt to be someone who is able to guide, but who at the same time can push people into black holes, with the result that they might have to swim around for a week but then come back with alternatives that I had not predicted. Maybe it’s also a little bit like John Cage, learning to work with an orchestra in such a way that on the spot I might say to someone, now you have to play your own tune and see what effect that could have on the total composition.

Wessner: So you see your role as encouraging a sense of either uncertainty or spontaneity…pushing people out of what might be their comfort zone in order to generate new approaches, new ideas for the project?

van Berkel: I’ve learned from teaching that you have to meander between your own talents and someone else’s in order to stimulate operational design. If it is not deductive or, inductive, if it is not dynamic in its operational systems, then you cannot motivate people. I don’t believe that the architect today needs to only work with other architects, or alone in a single production mode. That’s not how our society operates anymore.

Wessner: One more question about how the “network” works: Your partner Caroline was trained as an art historian. I’m curious to know, coming from an art history background myself, how a historian operates as part of the design team. I’ve read that she functions, in part, as a critic.

van Berkel: You also know that she did a . . .

Wessner: Urban planning degree, yes.

van Berkel: So now it’s combined. I’ll tell you how it works. What is most important for Caroline in design crits is that she discusses with the team how ideas are formulated and how these ideas are brought together. Her argument is often, if you guys don’t know how to formulate the idea then it’s probably a bad idea. I like that attitude a lot. Her critical dialogue with how we play with language, the intensity of the concept and with my influence there as well sets up a good balance between how we operate together, as well as with other partners. I find it really an amazing pleasure to have someone around who has another background than pure architecture alone. And that’s why, as Stan [Allen] said last night at the lecture, we invite others into the studio. People with maybe a fashion background, maybe a product design background, or a theoretical background.

Wessner: Introducing other disciplinary backgrounds into the design process to see what happens, a way to always refresh how you work.

van Berkel: As much as we can. It’s not always possible, because sometimes you’re constrained. But we try to do it if we take part in a competition, for instance, or we want to stir up ideas. We are always promoting the idea that we need to change the boundaries of the profession as much as we can. It happens every day in medical science, so why not in architecture?

Wessner: You didn’t talk about it last night, but you’ve been quoted elsewhere as saying that architects are the fashion designers of the future. What do you mean by that?

van Berkel: I think that architects could dress the future, but I don’t mean to say that we make fashion. Architecture needs to be far more speculative and even more visionary than fashion as it needs to still be consumable a few centuries from now. So architecture is not fashion in the literal sense, but I like the idea that we could play a bit more, explore the space between what we are as scientists—approaching architecture, on an academic or theoretical level—and allowing ourselves to be a little more frivolous or light-hearted about how we can uplift the profession. That is what fashion designers do so well, they work more with gut feelings than architects do. We have a tendency to predict everything with statistical arguments, which is a bit narrowing for the profession sometimes.

Wessner: So architecture needs to lighten up sometimes?

van Berkel: Yeah!

Wessner: Since we’re talking about fashion, let me ask you this: There are a number of critics who think that architecture over the past five or ten years became too much like fashion, that there was too much emphasis on making icon buildings, spectacles, that in the end didn’t really advance architecture. Perhaps too much focus on image or surface. What do you think?

van Berkel: I think it’s true to an extent. And I think that we were all part of that. The external forces of the profession—the political, the social, the economic—were so on top of us that we forgot at times to think about the internal regulations of architecture. But at the same time, if you compare the work produced in this period with other comparable phases of extreme economic activity in the history of architecture and art—phases that we now look back on as moments of high art—I think it has actually also been a highly innovative and fascinating period. Having said that, I also don’t think it is suddenly over either. We are not now in a completely different period. A lot of recent developments in architecture are still continuing. Fortunately there was also a good balance in this period too, like the exploration of the computational, of what geometry could do. There were all kinds of tests being carried out. But for me, these tests were not theoretical enough in relationship to the practice itself, to the production of architecture. Tests about building techniques. Because I’m really fascinated by how you actually realize things.

Wessner: Do you think that “starchitects” will continue to be a part of the profession?

van Berkel: It’s a somewhat sensitive question because, as we know, the role of the architect is connected to an individual. But what I try to say about the role of the architect in the future, and what I also explain to my students is, okay, perhaps it may be more difficult in the current climate to set up an office easily on your own, but there is an opportunity to be more collaborative. You see this in many, many firms that were set up over the last ten or twenty years, collaborative offices where three or four partners operate almost on an equal basis. I’m not saying that everything is going to change. But let’s also not forget that we so-called “starchitects,” all of us had difficulties with it, because such a term pushes you in a direction whereby you’re no longer a cultural producer, you’re a “celebrity.” But we are also thinkers, so hopefully we go beyond that. I cannot predict that this whole phenomenon of the celebrity architect will disappear, but I do think that there will be more variety. A similar thing is also happening to some extent in fashion today. Younger, smaller collaborative companies are springing up, made up of designers who have had to join forces in order to achieve.

Wessner: Let’s talk about infrastructure now. One of your earliest and most significant projects was the Erasmus Bridge and you continue to do infrastructure projects. Given that it is a hot topic lately in the United States, what are your ideas about infrastructure, how do you approach these projects?

van Berkel: My approach is similar to how I understand the evolution of the diagram to the design model. How perhaps a diagram can be seen as a map, or a design model can be seen as a map. Both give direction. It’s similar with infrastructure. I see infrastructure as the way that you can connect one program to another, or one space to another, in a building; how you operate within the architecture. It’s the only dynamic principle of connecting certain qualities in architecture. I like the metaphorical aspect of how it operates.

Wessner: That infrastructure can be something literal, like a bridge, but it can also be a metaphor for the program or a means to connect spaces within a building?

van Berkel: Yeah. Caroline and I were arguing earlier today that maybe “city planning” has disappeared, that maybe there is only architecture and politics now, because urban planning has been taken over by developers. This is very much the case in Europe. It is really a major problem we find. But I believe it is really important to discipline urban planning and discipline how one thinks about how to connect locations. And that’s what infrastructure is. Infrastructure plays an enormously important role in every layer of the principle of how one plans, organizes a building, and often how we can invent architecture. Think about the way Victorian churches were organized. The way men and women had their own doors, and the clergy another. The whole political and social side to urban planning and infrastructure fascinates me. Like how Manhattan operates with a grid system and the way that generated particular kinds of connections between production, consumption and high finance. If you really start to think about it, this whole structuralist approach towards infrastructure has only been enriched over the centuries. And that’s where I like to deepen it and refine it and understand it, and where possible to exploit it so that we can expand it further into hopefully more innovative architecture.

Wessner:To jump scales . . . or maybe not, depending on how you think about it . . . you’ve done a number of pavilions, which you referred to last night not as pavilions but as prototypes. You have an exhibition of several of these projects on view at Harvard right now. I was wondering how they function as testing grounds for ideas, how they feed the larger projects?

van Berkel: Well, as you know in the car industry it’s very normal to work with prototypes. I saw that with the car manufacturer we designed the museum for in Germany [Mercedes-Benz]. That’s when I learned a lot about what one prototype could do for maybe twenty cars. Maybe they don’t all make it to the market, but at least five cars came out as interesting variants from one prototype. And it’s not that I work literally in this way because that’s not how it operates, but we use pavilions as testing grounds in a number of ways. For instance the phenomenon of contemporary spatial experiences interests me. Space is scientifically so difficult to define. Even in science or in cosmology, they don’t know how to define it. But it is so interesting to try to define it because there have been amazing new theories suggesting that space, and time, are so complex and rich; that we might live in several times simultaneously, or that there is maybe something like an analogue time or parallel time. So I test these ideas in the pavilions, to see if some of what we tested earlier in the sketch models or in diagrams can be done on a larger scale. There’s an essay by Yve-Alain Bois on the work of Serra, called “A Picturesque Stroll around Clara-Clara.” It’s actually Serra who comes up with the theory about how you can’t have a full panoramic view of his work, that you have to step into it and then you discover the relationship between how you walk and what you see, the feet and the eyes together. This parallax experience, you can only test one to one. That’s what Serra argues, with one-to-one mock-ups he makes sure that his sculpture operates as he wants it to later on. It is fascinating to test when possible. It was also just coincidental that we were asked to do these pavilions and we always did them for this reason, to test ideas. But it is an enormous amount of investment, as you can imagine, because often there is little or no money for these pavilions, you always have to find your own subsidies or sponsors. But for us they are an incredible intellectual and practical investment to continue to test and work with, as they generate a lot of interesting spin-off. They become like theoretical models for thought.

Wessner: One final question, and this question only occurred to me because in preparing for our interview I was flipping through SuperDutch. Through the mid and late 90s, as I’m sure you remember, it was widely agreed that Dutch architecture and design was experiencing a period of incredible creativity and innovation, and the publication of SuperDutch in 2000 really marked that moment in time. I was wondering if there is still a strong sense of momentum and creativity in the Netherlands or have things changed in anyway?

van Berkel: You know Rem once had a very interesting interpretation about how careful we had to be with the name “SuperDutch,” because it’s very uncritical and patriotic. He asked what would happen if it had been a German group of architects calling themselves “SuperGerman.” I thought it was an amusing observation and I agree with him. But we should also be careful because in a way some of us cannot really be described as being completely Dutch in terms of our education or work experience. Many of us have been educated abroad and have worked internationally from the outset. But if there is something interesting in Dutch design, maybe it is that we all chose to live and work in Rotterdam or Amsterdam. The fashion designers Viktor and Rolf have their offices in Amsterdam, as do we, but that’s because we often think that it’s simply the most pleasant place to live. The quality of life is great, and of course we have a great airport, from where we can travel everywhere. So I sometimes think that it’s maybe more for practical reasons that we are all based here in Holland. It is true that in the Netherlands we have a strong cultural background in architecture, but I would say that what happened on a theoretical level and an academic level, and also on an architectural level, here in America during that same time period was as powerful as what happened for the Dutch. It just wasn’t recognized so much. Maybe because it was scattered over different places. Take for example the influence of Sanford Kwinter or Jeffrey Kipnis or Greg Lynn or Jesse Reiser. They were all my peers, and I was very close to them, super-close in the 90s, and that gave another twist to my work.

This interview was conducted on February 2, 2011.

Images: Black and photos by Inga Powilleit. Color images Justin Knight. Diagram courtesy of UNStudio.