Home and the world: The Sinai’s Gebeliya tribe

Sadia Shirazi writes about the transition from nomadic to fixed dwellings of the Gebeliya tribe in the Sinai Peninsula.

July 18, 2003

St. Katherine’s monastery nestled within the mountains of the Gebeliya tribal land. Credit: Sadia Shirazi.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Sadia Shirazi received a 2003 award.

Over the last forty years, the Gebeliya, a Bedouin tribe settled in St. Katherine’s region of the Sinai Peninsula, have shifted their basic residential unit from the nomadic beyt-al-shaar, to fixed dwellings. Two significant changes have accompanied this shift. The first is the inversion of the courtyard home, and the second is the privatization of the shig, a historically communal traveler’s space. Shorn of its meaning as an iconic structure that embodied the spirit of a nomadic people, the beyt al-shaar, or house of hair, is memorialized today as a symbol of the past. Now aptly described as a tent, it is rented by tribes for ceremonial or touristic purposes; in the past, it was an essential element of nomadic existence. With the geopolitical changes of the Middle East, the Gebeliya experienced a series of social, cultural, and economic transformations. I traveled to the Sinai to study the effect of these shifts on the construction, materiality, and divisions of public and private space in the dwellings of the Gebeliya.

Shifting tectonic plates and national boundaries have made the Sinai Peninsula a tenuous link between the African and Arabian plates. The land has changed hands between Egypt and Israel twice within the past forty years. A holy landscape for the three major monotheistic faiths, the peninsula is home to Mt. Sinai, or Gebel Musa, in Arabic, where the Ten Commandments are believed to have been revealed to Moses. The Gebeliya, whose name derives from the Arabic gebel, or mountain, are the “people of the mountain.” The recorded history of the tribe goes back to the sixth century when the Roman emperor Justinian brought stonemasons from Eastern Europe to construct a basilica and fortress to protect the monastery’s monks from Bedouin incursions. The progeny of these stonemasons, who eventually converted to Islam and took up a semi-nomadic lifestyle, make up today’s Gebeliya tribe. Though they have intermarried with other tribes, they are not considered ancestrally Arab and so are distinct from other Bedouins in Sinai. The tribe’s ancestral work as wage laborers for the monastery also distinguished them from other Bedouin, because this work fixed their movements and economic base limiting their migrations.

Prior to the Israeli occupation of the Sinai in 1967, Egypt had a hands-off policy in the Sinai. Interacting with only a few tribal sheikhs, Egypt otherwise left the land, except for army grounds, in the hands of the tribes with little interference or development. In the 1920’s the Gebeliya, unlike other tribes, had two housing structures, the beyt al-shaar, and a house made of clay. The beyt al-shaar was woven from goat hair, which is known for its strength and water resistance. The portable structure’s skin was woven by women and erected by men. The other house was constructed from local clay called tarfa that was mixed with water and left to ferment; this house was used in the winter, when snow might destroy the beyt al-shaar. The clay house was later constructed out of the regional sandstone, making it into a more permanent structure that eventually replaced the beyt al-shaar completely. During the Israeli occupation, tourism in St. Katherine’s boomed as researchers and pilgrims flocked to the area. This diversified the tribe’s wage labor, and increased income and population. As a result, Bedouin communities permanently settled for the first time, and invested more than ever before in their homes.

The older stone courtyard home consists of small rooms organized around a large central courtyard space, off of which the kitchen, storage, and sleeping areas are located. Outdoor and indoor spaces are flexible, with functions designated according to programmatic need and climate.

Hussein construction his new home out of concrete block faced with local sandstone. Credit: Sadia Shirazi.

Today, the men of the Gebeliya build new structures that are influenced by the apartments of nearby cities. The majority of Gebeliya live in one-story courtyard housing built out of sandstone or concrete block faced with sandstone. The courtyard is a predominant housing type in much of the Middle East, but no longer characterizes the urban apartment complexes of Egypt. While houses built purely out of sandstone are more climactically sound, warmer in the winter and cooler in the summers, these homes take more time to build than their concrete block counterparts. Salah Gebeliya, a friend and invaluable contact in the area, introduced me to his cousin, Hussein, who was building a new home in what he called “proper apartment style”, beside the courtyard house he grew up in. Hussein’s new housing plan consists of a series of cellular rooms haphazardly organized around a small, roofed interior space. The open air courtyard is now subsumed, shrunken, and roofed within the home. This inversion reflects aspirations of his class, which emulates the housing of an urban citizenry. Hussein’s mother is adamant about her preference for the courtyard housing typology. She emphasized that she wants to see views of the horizon from her place within the home, pointing to the significantly different material and psychological relationship of this new housing typology to its landscape.

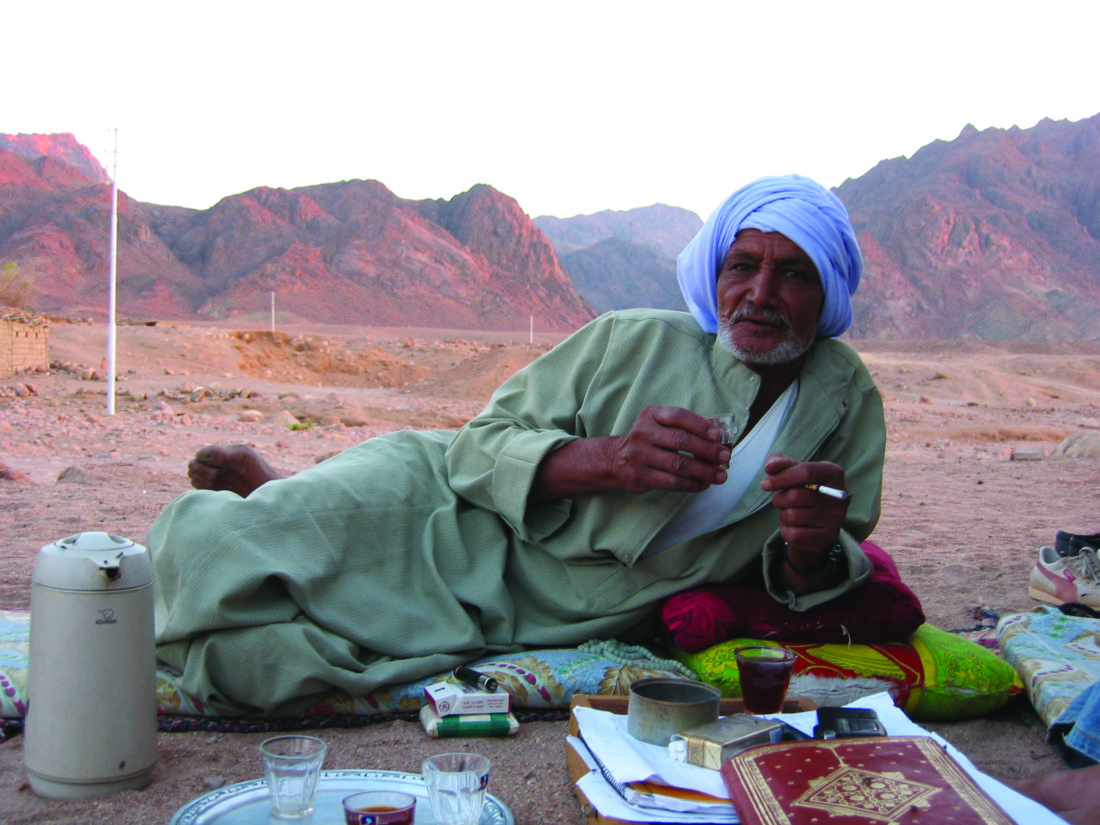

Credit: Sadia Shirazi.

The transformation of the Gebeliya home is also evident in the shig, a traditional structure built for the use of desert travelers. In the past, the shig was built as part of individual houses, or as a freestanding structure associated with a group of homes. When it was part of the beyt al-shaar, it formed one division of the house. When it was built for a group of homes, all the residents of the area worked together on its construction. During the time of the beyt-al-shaar, residents created an areesheh, or arbour, by erecting four pillars and roofing them with wormwood and branches of palm trees. When the stone house replaced the beyt-al-shaar, the areesheh became a stone enclosure roofed with branches of palm trees, built at some distance from the homes of the settlement to ensure privacy. The community provided the shig with coffee, tea, and wood. When guests were present it was incumbent upon all men to participate in social activity, called qarwah, based on mutual assistance and the premise that the guest is public responsability. Now, each house has its own shig attached to the rear wall of the house; guest space has become private property. The public space that is lost is a male, tribally communal space. The new space is a privatized familial public space attached to the exterior wall of a singular dwelling, which remains separated from the most private interior space. So the distinction between the innermost space of the home and that of the guest quarters remains intact. This distinction demonstrates the tiered aspect of public and private spaces; some frameworks of privacy endure, while others change.

Though the apartment remains an unacceptable housing typology for the Gebeliya, the inversion of the courtyard demonstrates the influence of aspects of the apartment on the individual house. The persistence of the shig suggests a particularized identity that keeps the Gebeliya distinct from the larger Egyptian populace. The Gebeliya are not yet incorporated as citizenry within the largely homogenous Egyptian polity, and remain separated by their dialect, ancestry, and built structures. When asked what his land meant to him, my friend Mohammad replied, “This land is the crossroads of my secrets. My place of birth. My paradise… They call us Bedouin and not people of civilization but we are civilized…The Israeli occupiers came to Sinai and left and so did the Egyptians. We are Bedouins; we are the only ones who can survive in the desert.”

Biographies

traveled to the Sinai in 2003. Since then, she has worked with the artist Krzysztof Wodiczko and written about architecture and urbanism in Egypt for Bidoun magazine. She is currently working on her masters of architecture thesis, which will be based on her research in the Sinai.

Explore

Temporary landscape and the urban meadow

Julie Farris details two temporary landscape installations on vacant lots that she created in Red Hook, Brooklyn, one of which became a permanent garden and community space.

In conversation: Marlon Blackwell and Rick Joy

Blackwell and Joy reflect on first meeting 15 years ago, approaches to teaching, and a shared sensitivity to place while "transgressing the vernacular" in their work.

Prototypical solutions

Brian McGrath comments on design proposals submitted to the League's Vacant Lots program.