Getting Fit in the Anthropocene

In a new installation, Common Accounts considers attempts to perfect the self during an era of global environmental crisis.

August 28, 2023

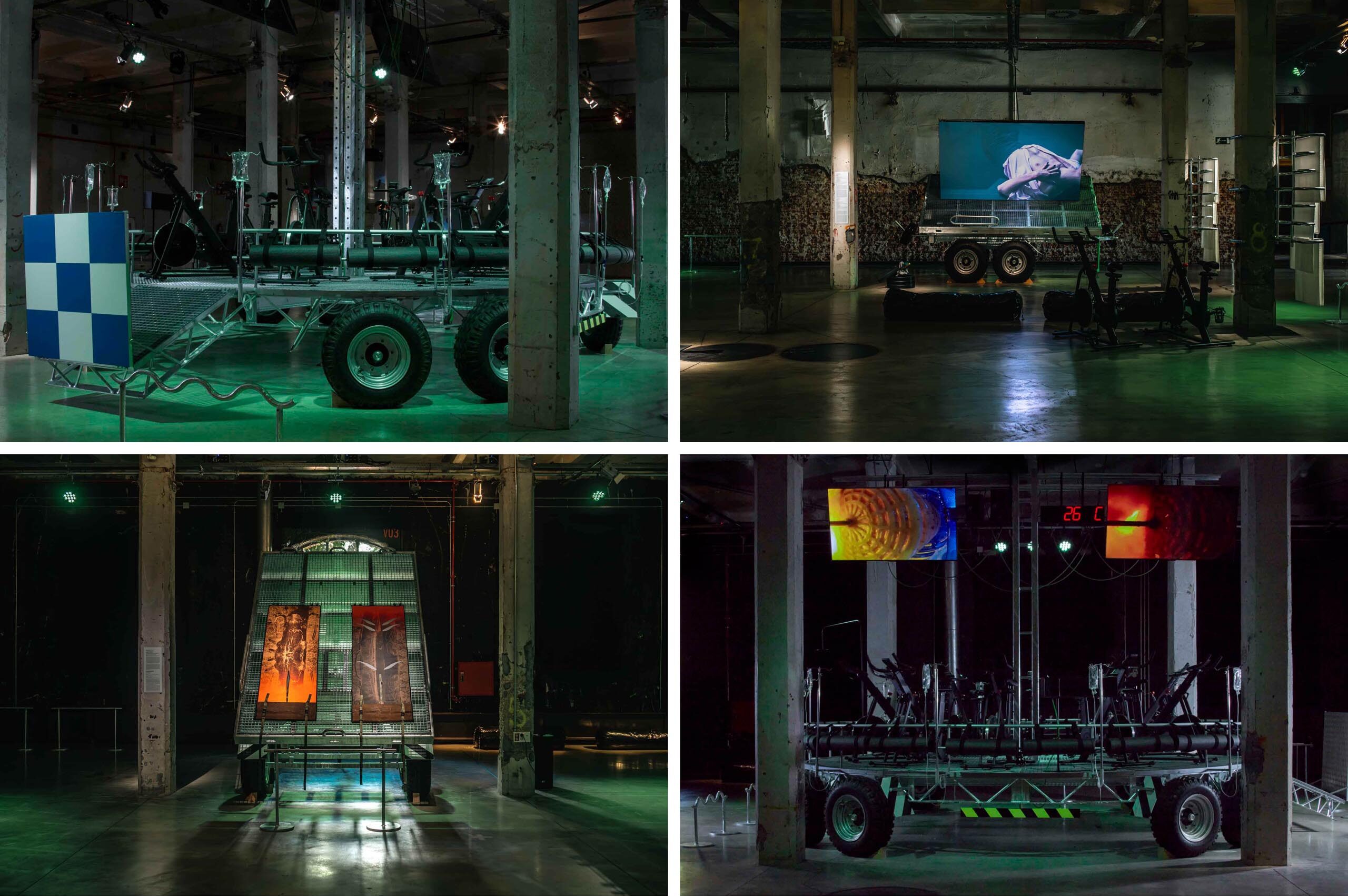

A view from the Clima Fitness installation featuring artwork by Itziar Barrio. Image credit: Geray Mena

Common Accounts is a 2023 League Prize winner.

What can individuals do about climate change, and what is climate change doing to us? These questions lie at the heart of Clima Fitness: Adaptability Rituals, a yearlong installation and artistic program curated by Maite Borjabad that’s now on view at Matadero Madrid, a contemporary art center in the Spanish capital.

Designed by Common Accounts, a practice founded by Miles Gertler and Igor Bragado in 2016, the installation builds on several years of research into the cultural origins and political ramifications of personal fitness regimes.

Gertler spoke with the League’s Alicia Botero and Sarah Wesseler about the installation.

*

Alicia Botero: Can you tell us about the origins of the Clima Fitness project?

Miles Gertler: The idea initially sprang from an essay called “Planet Fitness” that we wrote in 2019. The piece examined what we saw as the idiosyncratic reality that in this moment of unprecedented existential crisis under the threat of the climate emergency, people seem to be spending more time on the design of the self than ever before—perhaps in a moment where the self’s very persistence has never been more in doubt.

For example, in our research we encountered a fitness company called Les Mills that’s essentially equating the health of the individual body to the health of the planet. Les Mills is interesting because they’ve funded a climate lobby called Pure Advantage, and they produce not only fitness products and franchised gyms but also documentaries and books with titles like Fitter Planet, Fitter You and Fighting Globesity. We were really interested in the language they were developing that likened the planet to a body.

Screenshot of Amazon page for a book by the founders of fitness chain Les Mills. Image via Amazon.com

This essay turned into a larger inquiry into other situations where fitness and self-design were called on as coping mechanisms or strategies for escaping some large threat. We were also looking at the origins of contemporary bodybuilding culture, which often interfaced with larger projects of colonialism, empire, and military expansion. We were interested to find a recurrent relationship between the prospect of the body’s destruction and its consequent re-construction through self-design.

This work fell into the hands of the team at Intermediae, a program of Matadero Madrid, a large arts center housed in the city’s former slaughterhouses. They regularly commission a designer or an artist to conceptualize an environment for one of the large halls at Matadero, which plays host to performances, public events, artworks, talks and symposia, and other programming throughout the year. They asked us to develop the environment for this year’s show with this essay in mind, and sought to expand the conversation by engaging the curator Maite Borjabad to create a multivocal exhibition with works in video, performance, and sculpture that explored ideas of planetarity and adaptability.

Botero: Can you tell us more about the design of the exhibition?

Gertler: What we have produced is a series of devices—they’re essentially trailers, but they also borrow from the language of exercise equipment and refer to the language of resources, materials, and labor. They’re vehicular and can be hitched to a car or a truck. They carry the artistic cargo of the show and animate the visitor’s experience of each work.

The show opened with the performance Faster, Higher, Stronger, conceived by Mary Maggic, whose work questions tropes related to fitness and athleticism, like optimization and masculinity. This performance activated two of the stages we produced, in particular a large circular vehicle that’s viewed in the round, and which also hosts a number of infrastructures relating to the body, including fitness bikes, IV bags, showers, and yoga mats. It presents as an ad hoc assembly on wheels, able to respond to actual and imagined performances of the self and fitness on its platform. Its screens presented the cultivation of kombucha scoby, seen through endoscopic cameras positioned inside Mary Maggic’s acidic bioreactors hosted on another platform nearby.

Botero: You mentioned the relationship between fitness and empire. Can you say more about your research into this theme?

Gertler: Yeah. In “Planet Fitness,” we asked whether in this moment the human body was the final frontier of human impact, of human intervention, as a force for the design and transformation of the material world. That stemmed from Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley’s brief for the Istanbul Design Biennial in 2016, called Are We Human? The Design of the Species, in which they point to the fuzzy boundaries of the human body and the way in which it has always been designed and modified. Our thinking also drew from Rem Koolhaas’s Junkspace. The idea was really, is there any threshold that hasn’t been violated by the impact of humankind’s imprint, or by the penchant for intervention and reconstruction?

A visitor takes a selfie on the floor of Common Accounts's 2019 Refresh, Renew installation in Rome. The installation used the gym as a starting point for considering alternative funerary protocols. Image courtesy Common Accounts

We were also inspired by Michael Anton Budd’s The Sculpture Machine, which looks at how physical culture and bodybuilding culture emerged, always in relation to an environment that was also intended to be contained, controlled, or optimized. Which is also something that runs through the work of Mary Maggic, who explores and troubles the ethics and aesthetics of optimization that always end up at the self, in the body.

We looked at, for instance, the President’s Youth Council on Fitness, which was founded during the Cold War by Eisenhower and was later expanded by JFK. JFK even wrote an article in Sports Illustrated called “The Soft American” in which he’s basically arguing for the hardening of American bodies to resist communism. He posited that if the average American subject were more athletic, the country would be “harder” against communism.

So this framing of the body and its fitness as a site of resistance against influences deemed undesirable by a political mainstream has appeared at different points in history. And it’s perhaps no surprise that Gold’s Gym, that foundational gym on the American West Coast, in Los Angeles, was housed originally in a former USO [United Service Organizations, a nonprofit serving members of the military] facility warehouse. The relations between popular fitness media and the US military remain and evolve.

I think many of the tropes we associate with the toxicity of mainstream gym cultures are in many ways fundamentally about the extraction and production of value, in the same way that we think about landscape as harboring value to be mined and accessed in capitalism. So much of contemporary Western fitness culture’s language around the construction of the physique, “glowing up,” and bodybuilding aestheticization revolves around a language of cultivation, discipline, and labor that is at its core similar to colonial practices of prospecting, mining, cultivation, and “taming” of otherwise natural landscapes.

Sarah Wesseler: A number of your projects at Common Accounts have focused on death. How do you think about this exhibition in relation to that theme?

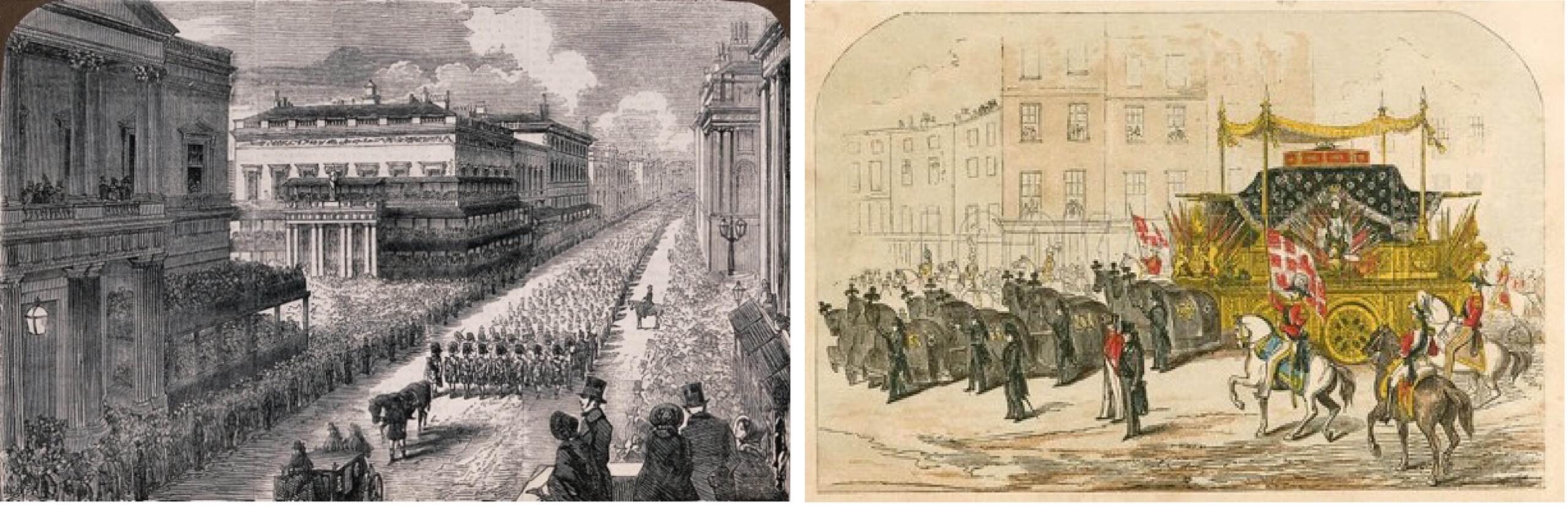

Gertler: Some of the key precedents that shaped our approach to Clima Fitness, leading to the design of this fleet of vehicles, are the funerary parades and catafalque structures that we’ve spent years looking at in our work on death and funeral. We keep coming back to parades and parade floats as a species of architectural typology that largely isn’t considered by architects or architecture.

One of the formative precedents for Common Accounts is the Duke of Wellington’s 1852 funeral parade through Victorian-era London, which was an enormous event. It’s estimated that millions of people came out into the streets to witness the spectacle of this parade. It was a design project, in part shaped by the architects Richard Redgrave and Gottfried Semper. Semper helped design the funeral carriage, which held the Duke of Wellington, who defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. And the portion of the funeral carriage that held his body was cast from the iron melted down from cannons captured from the French, literally materializing his epithet, “The Iron Duke,” re-materialized as this structure that held his body and rendered him visible to the crowd.

Parades are fascinating for their ability and responsibility to materialize people, communities, political concerns, and attitudes and urgencies. And in studying historical parades, something that became really exciting for us was the way events like these could animate the urban milieu and, in fact, became an urban milieu of their own. They became these sort of mobile urbanisms that were ephemeral, ritualistic, and intense.

We became interested in how a flexible arsenal of architectural devices, like parade floats and the other constituent parts of a parade process, could create an atomized urbanism in the contemporary city. So the approach that we took at Intermediae essentially consists of a number of vehicles which we were really thinking about as somewhere between parade floats and functioning trailers. They’re also built in part from gym equipment. So these are meant to be used for exercise, for performances—and we want the audience to engage these structures. They can be set up one way for the opening performance of the show and in another way for the regular hosting of the artworks. And they may reorganize and structure new spaces within the existing hall of Matadero, since they’re on wheels.

I think we can say that the installation itself is working out. Its devices are rehearsing the movements of pulling, pushing, lifting, rolling, rotating in support of artistic cargo which similarly considers the body in relation to planetarity and environment.

Wesseler: It’s interesting that you’re drawing on the legacy of parades as a collective spectacle that’s often been tied to political action, but also highlighting these intensely individualistic fitness regimes. It reminds me of a debate that comes up in the climate advocacy world about whether individuals who want to make a difference should focus primarily on lowering their personal carbon emissions or advocating for larger-scale change. I’m wondering how these tensions between the collective and the individual played out in the design of the exhibition?

Gertler: That has been a persistent question for us and our collaborators for this exhibition. We began with a kind of cynical point of view in the essay, “Planet Fitness,” essentially pointing to what we saw as the futility of these efforts to design the self as a form of resistance that could never really withstand the forces of climate change. But when we started to open up this conversation and have discussions with peers, colleagues, and the show’s curator, we began to shift away from a purely cynical stance. People largely want to do right by the planet, and the ethics of adaptability, self-design, and collectivity developed in the works in the exhibition hold within them an inherent optimism that deserves further consideration.

I think many of the artworks in the show test the boundaries between the individual body and a kind of collective idea of bodies and individuals in relation to this large rock that we all share. The artworks consider these issues both at the macro scale and at the scale of daily life. And ultimately, that makes us reflect back on many of the cases we first encountered in “Planet Fitness.” We realize that many people are simply trying to find a way to change what they can at the scale of the everyday, because that’s the scale at which they engage the world. And that’s ultimately a compelling narrative and reality.

So the act of working through the development and assembly of this show has been a fundamentally optimistic project in which we’ve started to see more clearly, I think, the generosity in a lot of these gestures.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Joel Sanders and Seb Choe: Body Politics: Social Equity and Inclusive Public Space

The leaders of MIXdesign, which serves marginalized communities, discuss their practice for Current Work.

On a Warming Planet, No Island Is an Island

N H D M's research into the impacts of climate change on small island nations highlights the complex networks linking communities across the globe.

Torkwase Dyson: Distance and perception in the wake of climate change

Interdisciplinary artist Torkwase Dyson speaks on race, sustainability, and access to equitable space.