Connective spaces and social capital in Medellín

Jeff Geisinger investigates the built environment's impact on social capital in Colombia's second-largest city.

The Deborah J. Norden Fund, a program of The Architectural League of New York, was established in 1995 in memory of architect and arts administrator Deborah Norden. Each year, the competition awards up to $5,000 in travel grants to students and recent graduates in the fields of architecture, architectural history, and urban studies.

Jeff Geisinger received a 2010 award.

In 2007, I read an article in The New York Times about “Medellín’s Nonconformist Mayor” and the city’s recent transformation. I was immediately drawn in by images of new iconic architecture, set against fields of mountainside houses. I thought back to my first exposure to Medellín, which is what many Americans picture when they think about the city — impoverished barrios, street gangs, and drug mafias. It came as a surprise when I heard Medellín described in such a positive light, with such inspiring buildings, and such a sense of optimism. I was determined to travel there to understand how the world’s most dangerous city had been transformed.

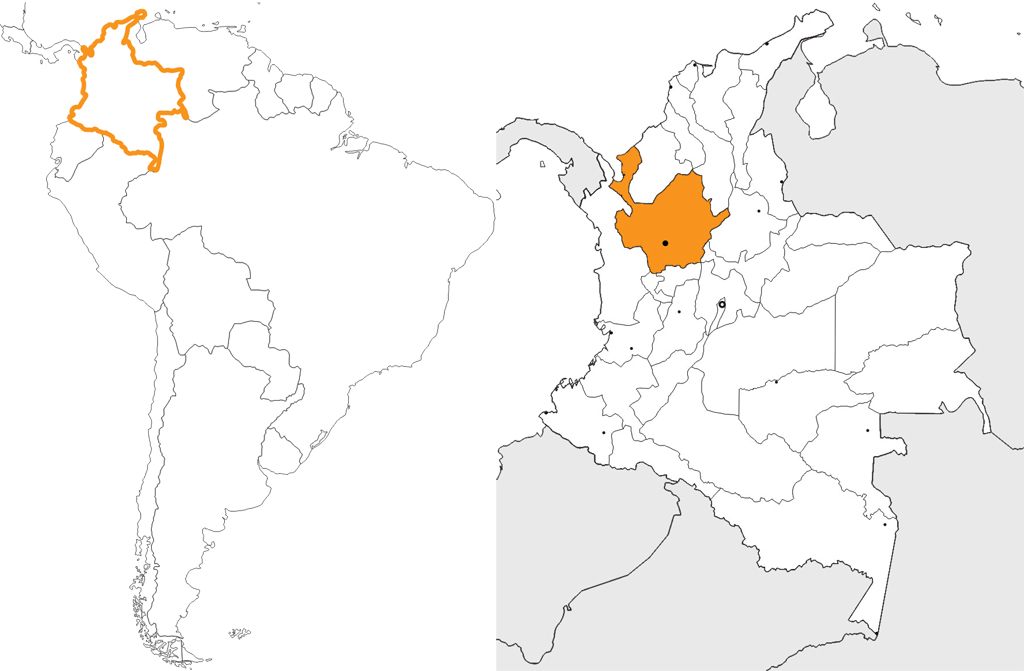

Colombia and Antioquia map. Credit: Jeff Geisinger.

What I hoped to learn by being there in person was how architecture played a part in making those neighborhoods livable, safe, and connected to the rest of the city. Which leads to the big research question I posed for my study: What roles, if any, can architects play in increasing social capital in poor urban communities?

Social capital

Social capital can be defined as the resources available to people through their interpersonal connections. The term is sometimes credited to Jane Jacobs, who examined the informal social contact enabled (or inhibited) by cities. Scholars like Robert Putnam have pointed out that social capital is on the decline in the US. The term is also used by urban youth activists like Lisa Sullivan, who offers another perspective on social capital in cities, especially that of poor neighborhoods. Engaging with inner city youth in Washington D.C., she observed a thriving associational life, and sought to harness existing high levels of social capital to energize young people as leaders for positive change.

I believe there is a spatial component to the way associations, networks, and relationships play out in cities, and that the public spaces we build can have a lasting impact on the connectivity between people and their communities. So I traveled to Medellín to take a close look at the informal fabric of the hillside neighborhoods to see what relationships exist between the creation of space and the development of social capital.

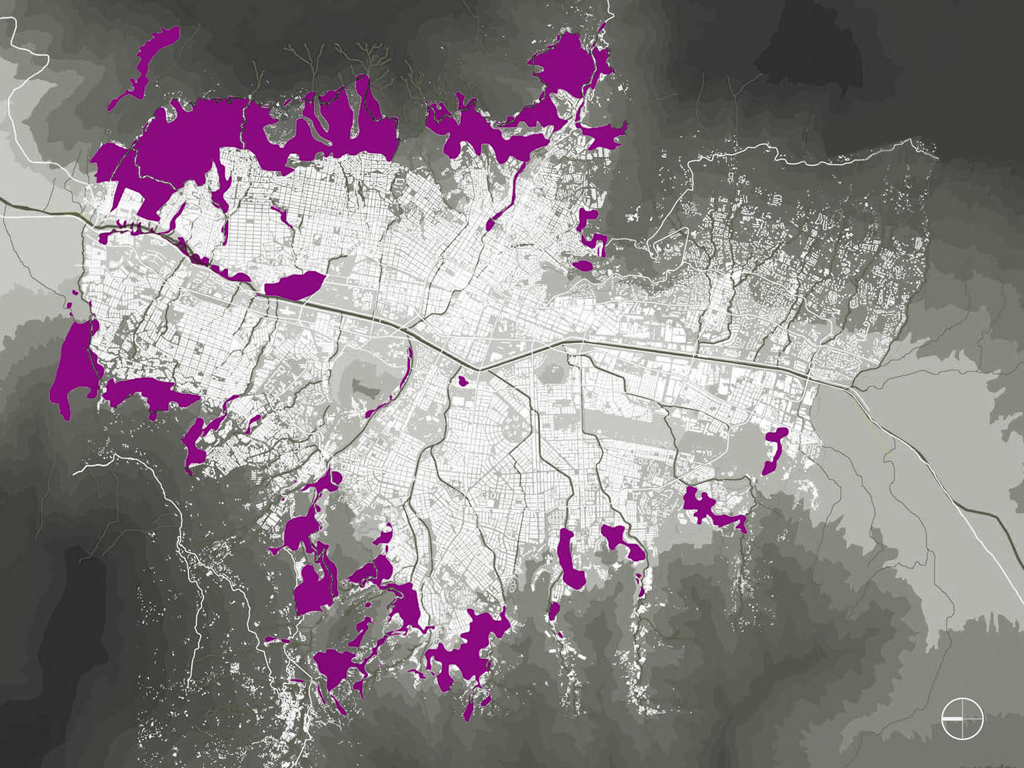

Map of Medellín showing the location of informal settlements. Credit: Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano; Overlay: Jeff Geisinger.

Context

Medellín is Colombia’s second biggest urban center. The Medellín River bisects the city, which rises up along a sloping valley. Many of Medellín’s impoverished neighborhoods are informal settlements located along the periphery. After a period of intense violence and urban decay, the community voted for an independent civic movement, led by former mayor Sergio Fajardo, committed to urban renewal and social inclusion.

Research structure

There are two types of “Connective Spaces,” a term I use to describe places where urban associational life unfolds. “Cultural Connective Spaces” are the facilities that connect people to educational resources; in Medellín, they take form primarily as Library Parks, or hybrid cultural and educational centers. “Local Connective Spaces” are the plazas, parks, bridges, and promenades that informally bring inhabitants together with one another and with other neighborhoods.

Library Park La Quintana. Credit: Jeff Geisinger.

During the grant period, I traveled to Medellín twice — for five days in October 2010 to chart my itinerary and make initial contacts, and for three weeks in March 2011 to carry out the main part of my research. Using photography, video, and mapping, I documented the design features of public spaces in several of Medellín’s vulnerable neighborhoods. I investigated the organizational factors that underlie these urban improvements by conducting interviews at the EDU (the Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano, or Urban Development Wing), the Department of Urban Planning, nonprofit community organizations, and local universities. I also interviewed average persons on the street, to hear their perspectives on the new projects. To document my experiences and upload interviews, images, and video, I kept a blog called “Connective Spaces and Social Capital in Medellín” over the course of my research.

Findings

I saw beautiful projects at various scales, but it wasn’t just their aesthetics that inspired me. In my travels, I encountered a process that takes architects beyond the typical project delivery paradigm, to work collaboratively with communities, building trust and ensuring lasting results.

As an architect of Cultural Connective Spaces like university buildings and museums, I assumed I would focus on spaces such as the Library Parks La Quintana and España, which I visited in the Northwest and Northeast regions, respectively. As successful icons promoting neighborhood pride, these cultural spaces make available previously inaccessible information and job-training resources to the city’s poorest residents. But as I delved beyond these more famous projects, I found that what I could learn from most was the collaborative process between community members and designers behind the street level improvements.

The project that exemplifies this community-centered approach is what I’ll refer to as the “local master plan” (called the Proyecto Urbano Integral, or PUI). This is a series of interconnected public spaces that aims to improve the quality of life for the residents of Medellín’s poorest neighborhoods, not only through physical built improvements, but also through participatory decision-making and interdisciplinary coordination.

Map of Medellín the five Proyecto Urbano Integrales (PUIs). Credit: Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano; Overlay: Jeff Geisinger.

There are currently five local master plans in Medellín, which are designed and administered by the EDU, the municipal Urban Development Wing. Alejandro Echeverri, former Director of Urban Projects under Fajardo, told me in an interview that, in a geographical sense, these strings of public spaces could be thought of as “the central nervous system” of the once-neglected and divided neighborhoods. To improve mobility, the projects link pedestrian space with bridges, ramps, and stairways. Environmental hazards like unstable waterways are remediated and converted into public promenades. For safe and active community gathering, they include plazas, terraces, and amphitheaters. And where critical infrastructural spaces are lacking, the EDU builds recreational facilities and police stations along the master plan trajectory.

I learned a lot about the projects by talking to officials, but also by talking to Orlando García, a local radio communications worker and liaison between his community and the EDU. He told me that this process is truly about collaboration. In his words, “we found people with great technical knowledge who stepped down from their pedestals to engage in a dialogue with the community.”

View of rehabilitated housing along the Juan Bobo Stream. Credit: Jeff Geisinger.

In my report, I focus on three exemplary local master plans. One component of a larger series of spaces I examined in the Northeast region is the environmental recovery along the Juan Bobo stream. Through neighborhood consensus building and community visioning workshops, this project rehabilitated and relocated unstable housing structures, cleaned and fortified a tributary of the Medellín River, and made available a wealth of green space, pedestrian promenades, and communal terraces in keeping with the informal fabric of the neighborhood. The multi-disciplinary team at the EDU carried out the project without displacing a single resident, turning one of Medellín’s most economically depressed and unsafe neighborhoods into a thriving and unique community.

In the second example I viewed a series of projects under construction in the Northwest Region, including projects such as Paseo Calle 104 and Parque Patio Bonito that prioritize pedestrian access and increased park space. Here, before any designs had begun, architects and bureaucrats involved the local community, who were referred to as “actors of their own social progress.” In the words of one neighborhood leader I met, the experts “recognized the inhabitants of this community as citizens, not as beneficiaries.” This local involvement wouldn’t have been possible without the already existing rich associational life.

In my third example, I looked at the local master plan of Comuna 13. Its projects seek to improve mobility for its inhabitants and create safer community spaces. This is particularly important here because of regional conflicts with militant groups, and more recently, gangs. A new line of the Metrocable was built to connect neighborhoods with the city center, and a recent Library Park activates the area near the cable station as a gateway and gathering place for community and youth groups. Despite the risks posed by gangs in the area, the EDU hopes that their involvement with the community and their investment in public space will eventually transform Comuna 13 into a peaceful, more livable area. This rings true for the residents that I met: during a visit to a rehabilitated public plaza, I spoke with a community member who described her new space as both a “meeting point” and a “living room” for the neighborhood.

In one of the most at-risk regions of Comuna 13, the EDU planned a series of public escalators to improve mobility and security for about 12,000 inhabitants who live along the neighborhood’s steep slopes. This innovative type of urban infrastructure would be integrated with green space and public terraces, and cut commuting time in half. Forming committees of neighborhood parents and children during the design phase, the municipal architects communicated the benefits of the new transportation network and taught safe and respectful practices when riding. I attended a meeting in which a social coordinator, using design pamphlets made by the project’s architects, cultivated awareness and a sense of ownership with a group of neighborhood children to promote the sharing of knowledge and respect of the project to their peers. The community even participates in model-building workshops with the architects to raise excitement about the escalators and envision the positive changes to their neighborhood.

L: Plaza in the Santo Domingo Savio neighborhood | R: Puente Mirador connecting the La Francia and Andalucia neighborhoods. Credit: Jeff Geisinger.

Despite the obstacles, the projects I explored in Medellín demonstrate architecture’s capacity for building social capital in marginalized communities. In a city where violence is as deeply rooted as it is in Medellín, thoughtful design has the most potential to succeed when accompanied by social and institutional underpinnings. Hearing local residents speak about their experience with participatory design, observing architects help at-risk youth envision safer streets, and learning how multi-disciplinary teams of professionals build neighborhood consensus, I encountered a collaborative methodology whose added value lies not only in the final, physical product, but just as importantly in the cohesion of its community stakeholders. I saw hope in the architects and communities I met for this connectivity to endure through future generations.

In my work today, I am applying what I learned in Medellín to a joint research study between Ennead Architects, my current employer, Stanford University and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to study the potential for architecture and infrastructure to mutually benefit both existing and refugee communities. My research experience in Medellín, along with the lessons I learned about participatory design, environmental stewardship, and community engagement, will play an instrumental part in an upcoming field research trip to a camp in Africa.

View of Medellín from the Northwest region. Credit: Jeff Geisinger.

Biographies

is a designer at Ennead Architects and a registered architect in the state of New York. His experience includes the Yale University Art Gallery Expansion, New York City Center Renovation and Restoration, and the State University of New York Center for Agriculture and Natural Resources at Cobleskill. Prior to joining Ennead, Jeff worked as a designer with the studio of Guillermo Vazquez Consuegra in Seville, Spain. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Rice University.