Can rural black churches survive sprawl?

Long a vital community resource in the South, African American churches face growing threats. Cadaster believes designers can help.

An interview with Brooklyn-based Cadaster, a recipient of the 2018 League Prize.

After the Civil War, freed slaves founded churches throughout the American South. Although many of those congregations still exist today, they face threats ranging from rural gentrification to vandalism.

In 2014, Cadaster founders Gabriel Cuéllar and Athar Mufreh began working with Texas’s St. John Baptist Church to understand the factors affecting both its physical presence and its social function. Their goal: Help the church preserve its architecture and community while communicating its historic importance to the broader public.

The Architectural League’s Catarina Flaksman and Antonio Huerta spoke with Cuéllar and Mufreh about the project.

*

Antonio Huerta: How did you first encounter these churches?

Gabriel Cuéllar: My parents used to live outside Houston, close to one of the churches, St. John Baptist Church. I always wondered what it was, because it’s very unusual in this context. The neighborhood is a typical suburb with single-family houses, palm trees, fences, and pools. When you come across this part of the neighborhood, the white wooden chapel with its burned rear section stands out pretty strongly.

St. John Baptist Church. Credit: Cadaster.

I went to the church one morning, perhaps naively, to talk to them and find out what plans they had, as they had survived an arson a few years earlier. Over time, we became close to the congregation and got the sense that they welcomed us to be a part of their community, which has been really great. Slowly we developed a project, which is about revitalizing the site through preservation of the building and urban design of the property.

Doing research on the particular history of St. John led to other discoveries about the area, these churches, and the nature of property in the US. They used to be rural churches, but since Houston has grown, they’re now embedded in the middle of the suburbs, which presents particular conflicts and opportunities. We’ve been working with them since that time.

Cadaster map of Fort Bend County churches.

Catarina Flaksman: When you found the church, was it abandoned or was it being used?

Cuéllar: It has been in continuous use since 1900, but the building itself appears quite closed unless you came by during the service hours. That’s why a lot of people didn’t really pay attention to it.

Over the 20th century, the congregation undertook several renovations of the building in an attempt to fortify it because of incidents of vandalism that occurred, especially when the real estate development of the area increased. Today it looks like a simple box, but originally it had architectural elements: big windows and a wide porch that opened up to the street.

Rendering showing a community porch as part of Cadaster’s rehabilitation vision for St. John. Credit: Cadaster

Huerta: Were you already interested in issues around land use, or was that something that came about after you began working with the church?

Cuéllar: Both, I would say. In general, we are very interested in land politics and real estate in the US and around the world. The land politics issue is something that we consider in all of our projects. Not every project has a definite connection to it, but it’s a typical urban condition to take into account. We use it as a conceptual idea in architecture and urban design.

What’s special about this church is its particular ownership situation. The title deed they possess has a reverter clause, which stipulates that the land can only be used for church services. If services ever cease, the land will revert to the original owner or his heirs. It’s a precarious situation where they don’t have actually permanent ownership of the property.

Mufreh: However, because this community has been so strong over the past 150 years, by simply going to church they have been able to maintain their ownership. It’s an example of collectivity creating a common space in a sea of private property.

St. John Baptist Church, Texas. Credit: Cadaster.

Our interest in land politics was developed through previous experiences, I would say. However, working on this project was a big push to develop our ideas, as it involves complex questions of real property and preservation.

Flaksman: Can you talk more about the history of these churches?

Cuéllar: The church is in an area called Sugar Land, named for the sugarcane slave plantations that were once there. By the start of the Civil War, this county in Texas had one of the highest slave populations in the South.

After the Civil War, rather than being owned as property, the freedmen [the term given to former slaves] gained the right to own property themselves. One of their main ambitions was to build churches. Virtually all their churches have this vernacular architecture: a wooden building on pier-and-beam foundations with big windows, a porch, and two steeples, all painted white.

We haven’t quite figured out why this form became so prevalent across thousands of miles of the American South, but we know that pastors and families were often moving around in search of work and in order to establish towns and churches.

St. John Baptist Church. Credit: Cadaster

As a result, the churches have been a kind of community or welfare center for freedmen and their descendants for over 150 years.

Mufreh: These churches are facing tough times, but they have a very strong and relevant political message. Our concern is that with time this type of building, along with its rich cultural and political heritage, will vanish or lose its resonance.

Huerta: Is the church losing members, or is it still going strong?

Cuéllar: The particular church that we’ve been working with underwent a significant reduction in members over the past couple decades, as far as I know, but it is starting to grow again. These were rural communities, but with all the new development encroaching, a lot of the people around here were displaced by what you could call rural gentrification. The land that was originally rented by the churchgoers was purchased and they had to move further from the church.

These churches are facing tough times, but they have a very strong and relevant political message.

Mufreh: Probably only 15 to 20 original buildings remain from the 50 or so freedmen churches that once existed in the Houston area. Most were demolished and replaced with new buildings.

Flaksman: What stage is the project in now? Are you still working with this particular church?

Mufreh: The work process has been lengthy due to funding issues and extensive discussions about the design and vision of what this place could become. We can’t impose our thinking when working with a community. What some members envision for the church is quite different from what we value in the current building.

Just a couple months ago, the church informed us that they now want to demolish the building. It was a very frustrating moment, but they got funds to build a new church.

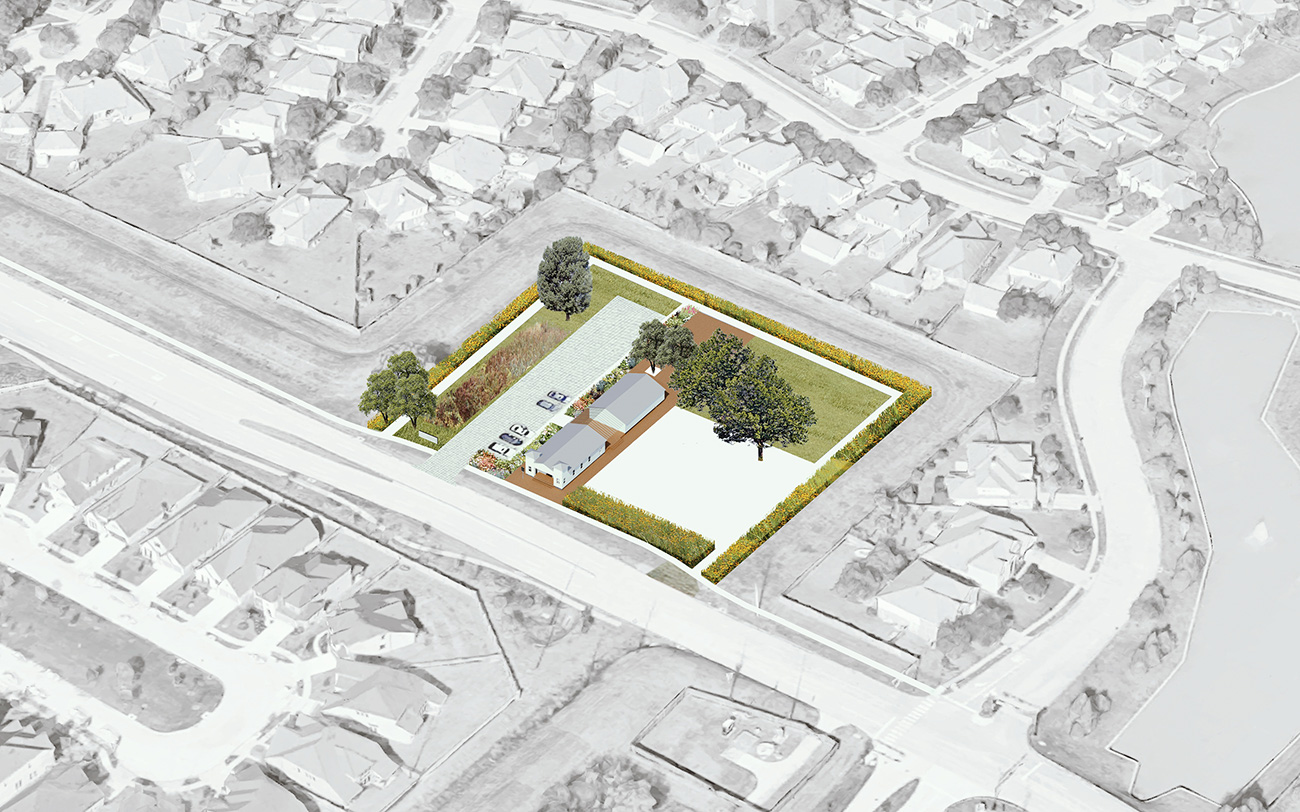

Cuéllar: Our original proposal for the project was based on the church’s ambition to reconnect with the neighborhood around it and honor the rich history of the site. The site design we developed used trails and sidewalks to make an interface between the site and its surroundings, and we also made plans to rehabilitate the historic structure.

Cadaster’s proposal for the site of St. John Baptist Church. Credit: Cadaster.

But recently the congregation expressed interest for something more typical to the area. They opted for a large pre-fab building with a concrete parking lot.

It’s complicated, because in this project there are many different voices. But for us the project’s not over. Things sway back and forth, so hopefully we’ll get back involved more directly.

Fundamentally, we wanted to be a part of that place, because if something doesn’t change for the better, in ten years from now it might not exist anymore. So the whole point was, what can we do as architects that can help them revitalize what they have and become something that the community can appreciate and value? How could we understand the history and support this great collectivity?

The underlying goal is that they succeed in preserving the vitality of their community, even if they don’t do exactly what we think is a good idea architecturally, spatially, and urbanistically.

Mufreh: But this project is not only about St. John. There are other sites that we have started to get involved with to try to support their history and architecture.

Flaksman: Is the City a part of this conversation? Do they have any interest in preserving these buildings?

Cuéllar: It’s hard to get a straight answer, because there are many different municipalities and counties involved in this area. We spoke with the Fort Bend County Historical Commission. They are really interested in, at the minimum, documenting all these churches. Hopefully we can work with them.

Mufreh: We were able to help get the church a historic site marker from the State of Texas, and there are a lot of supportive individuals working in the various sectors of government.

The church’s historic marker. Credit: Cadaster.

Cuéllar: The municipal and the county governments are definitely allies in making sure that these communities are supported. But we have to be vigilant that the measures they take make sense. Just because you do something doesn’t mean it’s going to be an improvement. It becomes trial and error—at least, that’s our perspective as a young practice that took on a project without a client or a commission. It’s tricky.

Flaksman: In general, what can architects do to bring more attention to the relationship between politics and land?

Cuéllar: Land and real property are taken for granted. It’s something in the background that sets the basic infrastructure for building and for cities. But today, the dynamics of the land itself are not really part of our creative capacity or our ethical realm of thought, so to say.

We hope that the freedmen church project and all the issues it raises about real property could be a model for exploring the politics of land more.

Interview edited and condensed.