A Platform for Something to Happen

Jennifer Newsom and Tom Carruthers discuss their conceptual art and design practice.

December 15, 2023

Columbus Columbia Colombo Colón, Dream the Combine’s 2021 installation for Exhibit Columbus in Columbus, Indiana. Image credit: Hadley Fruits

Dream The Combine is a 2023 Emerging Voices winner.

Trained as architects, Tom Carruthers and Jennifer Newsom worked for New York firms before founding installation-based practice Dream the Combine in 2013. They have since realized a number of large-scale public projects that invite visitors to view their surroundings in new ways.

The League’s Sarah Wesseler spoke with Carruthers and Newsom about their work.

*

Sarah Wesseler: You both studied architecture and worked in firms, then shifted to an installation-based practice. Can you talk about that shift from a traditional architecture practice to more of an art-based approach? What opportunities and challenges did you find along that route?

Jennifer Newsom: When we started the practice, we took on all sorts of different types of work. Some of the projects were related to work we had previously done in larger firms: a strategic space plan for a technology company in Vancouver, feasibility studies for a charter school in Minneapolis, residential projects in Miami, Seattle, Minneapolis, and Vancouver . . . Yet at the same time, we were doing these conceptual installations. The installations were the most fulfilling and catalyzing work we did in the starting days of our practice.

By doing and making, we were answering simple, fundamental questions: What are we interested in and how can our work speak? Can we find a way in which our individual motivations can be synthesized into this work? Do we enjoy working together? Luckily, we got some compelling answers that encouraged us to keep going.

Now we are reflecting on the last ten years of the practice. We recently had a studio visit with the artist Carrie Mae Weems. She looked thoughtfully and piercingly at our work and noted that we operate as conceptual artists working across media, be it installation, architecture, film, drawing, sculpture, writing, et cetera. We talked with her about the difficulty of refining how we describe ourselves—to ourselves and to others—so that we can be seen. Carrie Mae’s statement felt resonant, and like an opening. It was a way forward. Installation-based work, sculptural work, making films—all of these forms of artistic production have been ways for us to exercise our own voices. These are the things we felt we needed to do to communicate what was important to us in a specific time and place.

Longing, a 2015 installation in Minneapolis built within a segment removed from that city’s 8-mile-long pedestrian bridge network. Image credit: Caylon Hackwith

Tom Carruthers: The trouble with asking us one question is that you will likely get two answers.

When we started our practice, we were working for other folks. This was after 2008, so we were fortunate to still be working. There began a trickle of opportunities. Diller Scofidio + Renfro, where I was working, had an internal grant opportunity, which I won, to revisit an earlier set of ideas that had been let go in undergrad.

These ideas were front of mind when we were asked by some friends at Columbia GSAAP to develop a proposal looking at the subway system in New York City. That was the first time we worked together. We looked closely at the ends of subway platforms, probably one of New York’s least desirable public spaces. Our proposal, Space Destroyer, visually collapsed the intervening space of the subway tracks, bringing together different neighborhoods across distance. The work was shown at the New Museum’s Festival of Ideas in the New City and in a book our friends self-published.

There was a joy in doing the project that was unexpected. We felt like we were dealing with something that was a bit outside of the language we knew at the time.

In this period, we were also raising our first child. So there was perhaps a willingness to have a beginner’s mind. We made the decision to leave New York City and start our own practice. We didn’t quite know where we would land, but we had whispers of work in Jennifer’s hometown of Minneapolis, so we started out there. But before beginning that first project, the aforementioned feasibility plan for a new charter school, we took a trip to a place we had wanted to visit for a long time.

We had enough miles accrued on a credit card to get the three of us to Egypt for the price of one. We went for a month: three weeks in Egypt and then a week in Morocco. “Let’s go and see what Imhotep was up to.” [laughs] What does that actually look like 5,000 years on?

And there is, speaking for myself, a deep imaginative life in those projects that was beyond a kind of trite symbolism, and something that was much more manifold—you had a feeling of deeper significations accessible in those works. We came up in a relatively traditional architectural education, and that trip allowed me to call B.S. on some of it.

I studied sculpture and worked as a sculptor in New York for a few years before going into architecture school. I worked for Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, and also at length with the sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard. For each, I learned about deep commitment to taking responsibility for your inner life as a creative person.

Ursula talks a great deal about horizons of metaphor in her work. And architecture, at least in my experience, can often get quite obsessed with ideas of symbol, where meaning optimizes towards a particular singular, powerful interpretation. And for us, metaphor has been a way to create more opportunities. This idea of two things in a kind of unstable relationship: It doesn’t just work at the level of composition, or poetry, or conception, but it also works at the level of practice. It allows a kind of a way of thinking where neither Jennifer nor I feel that we need to compromise when each of us have a different intention. Both things can be held together.

Wesseler: A lot of your work explores ideas of place and meaning. Can you talk about your process for thinking through what to highlight or not highlight in particular places, or what kinds of meaning to emphasize?

Carruthers: We’ve been engaged in dialogues around site specificity and context in our practice. We are conscious of understanding competing and uneven processes, such as the morphology of a particular place. Why did it come into being in the way that it did? What are some of the different ways that a particular space can be read? Who is welcome there? In the early stages of a project, the conversations between Jennifer and I are looking for what’s crossgrain: What is latent but perhaps not acknowledged? Are there ways to deprivilege a particular space to open up capacity for new stories?

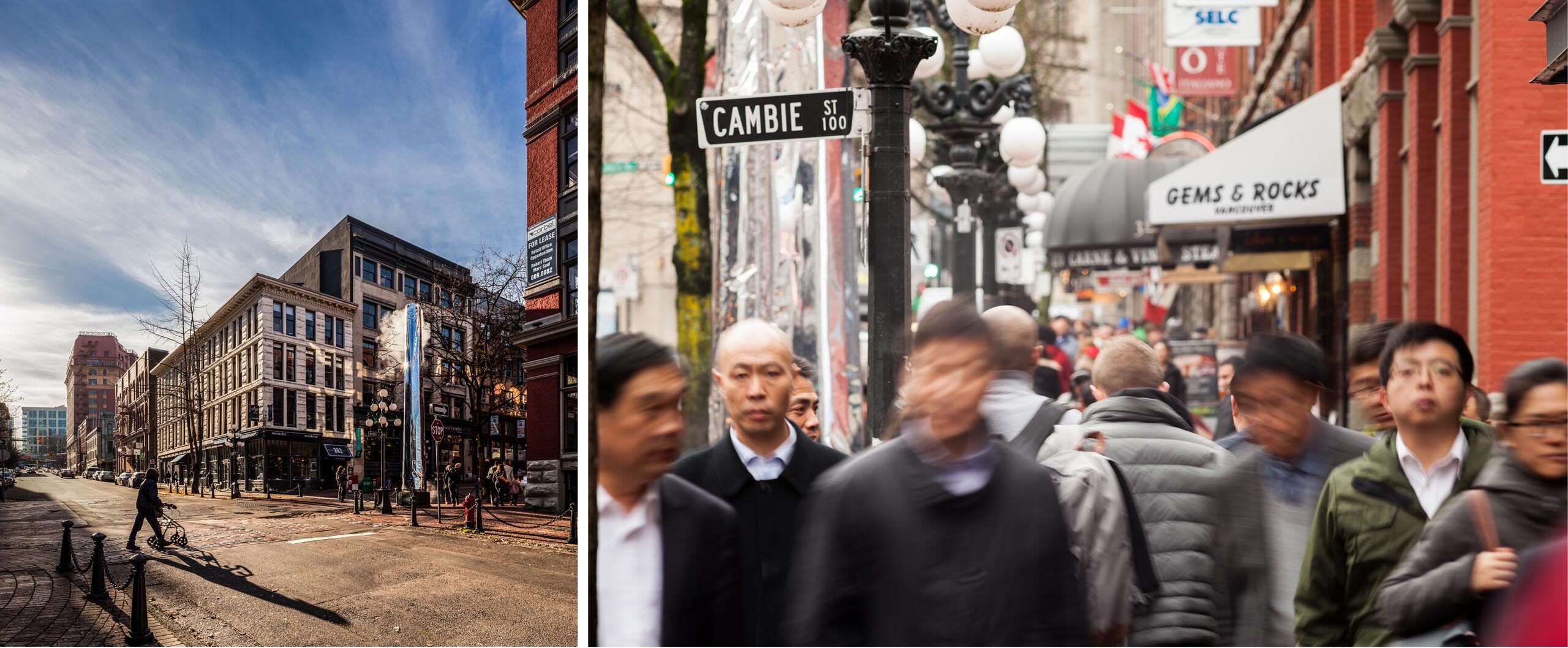

Make it Rain, a 2014 installation in Vancouver, Canada. Image credits: Andrew Latrielle

Newsom: In the consideration of site, we’re trying to understand context not only as the physical reality of the place—what are our site constraints, what is the geologic material, that kind of stuff—but also the sociocultural dimension of place.

There’s an article by Sara Ahmed where she talks about what’s in the room before she arrives: the conditions that prefigure how we might even interact with one another in that context. Each place has certain social codes of how you’re meant to behave, various mechanisms of control. We are interested in disrupting these patterns.

We can be expansive about what we choose to highlight. It can be intuitive and begin from what we feel when we are there. It can come from conversation and listening to other people who use that place. Or from walking. We did a project called Clearing at Franconia Sculpture Park in Minnesota, and for the first ten days of our artist’s residency I just walked the property over and over again. There were certain connections between elements in that landscape that we could start to respond to.

Clearing, a 2017 installation in Minnesota’s Franconia Sculpture Park. Image credit: Caylon Hackwith

But for other projects, the thrust comes from deeper research about the people, movement on, dispossession, and ownership of that land. What we bring forward about the context differs in each place. We put out feelers and question with a specific lens, but we are also willing to let a place speak and follow the leads as we find them.

Wesseler: With public installations, the artist’s relationship to the end user—the person who experiences the work—is different from that of a standard firm-style architectural commission in the sense that, in the latter, the designer has some idea of the needs, tastes, backgrounds, etc. of the people who will be using the building, at least initially. As you’ve moved into conceptually driven work in public spaces, how have you thought about this transition to an audience that could be, in theory, anyone? To what extent is it important for you to transmit very specific concepts or ideas through your installations to this wider, more amorphous audience?

Newsom: The work has resonance on a lot of different registers. Many people just go there and experience it even if they don’t know anything about what it is. You don’t have to be an expert about architecture, theory, or the larger concerns the project is stemming from. Hopefully you think, “This is a cool experience and this is beautifully made, and it speaks to me in some way.” I can inflect that experience through conversation, but I am really interested in what people bring to it that is new for me to discover.

Hide and Seek, commissioned for the 2018 Young Architects Program at MoMA PS1. Image credits: left, Pablo Enriquez; right, Brandon Polanco

I can’t control how people interpret our work, and I am not interested in controlling it. I bring my motivations and other people bring their own histories with them. I’m interested in creating a platform for something to happen. That looseness, that open-endedness, is an important part of what we’re doing.

Carruthers: When the project’s up, that doesn’t mean it’s done. That moment of contact where the project opens to a larger group of people can be anxiety-provoking, but the anxiety of it is interesting to me. If the work is super determinist—if I already know what the result is going to be—that’s not so interesting.

I think the way we talk about concepts in creative practice is worth continual revision and opening up. It’s not so much a noun—sometimes, the idea of “concept” as a postulation may actually be more of a verb. It is something continually made.

Interview edited and condensed.

Explore

Ursula von Rydingsvard lecture

Artist Ursula von Rydingsvard's hands-on, physical working methods and intuitive approach to monumental form-making are illustrated through a series of recent projects.

Aranda\Lasch lecture

March 5, 2015 | Benjamin Aranda and Chris Lasch | Blending history and storytelling with design driven by computation, Aranda\Lasch’s projects often grow from one repeated module.